The Walkley Awards for Excellence in Journalism is a black-tie, invitation-only, gala event fuelled by alcohol and rivalry. A packed room listened to SBS news presenters Anton Enus and Mary Kostakidis compere the show. One highlight, which I missed because I'd popped out to the computer to google Jack Marx, who won the feature award for 'I was Russell Crowe's stooge', involved Glen Milne, a well-known columnist, and a lot of shouting.

After rushing back into the living room, having registered the shouting, I saw him removed from the stage by security people, and heard the crowd buzz with excitement. An event! Something odd happened! It was soon over and they quickly got on with the show. Among the other highlights, for me, was Tim Flannery being short-listed for the non-fiction book award for The Weather Makers. Another interesting moment occurred when Kate Geraghty, winner of the major award for photography (she also won another award tonight), gave a very short speech: "OK, I'm a photographer so I don't know what to say." She seemed flabbergasted, and kept nervously brushing the hair out of her eyes.

Finally, an award that I didn't see given, but which was included in the closing sequence of unshown awards, was presented to a young woman in a black dress and with curly hair, who could be seen elegantly approaching the stage just before the credits rolled down the screen. It was Chloe Hooper, who won the magazine feature award for her analysis of the Palm Island affair. In fact, I had written about another brillient piece by her earlier this month.

Thursday, 30 November 2006

Mollie Gowing, of the famous Australian Gowing retailing clan, has donated 400 works of Aboriginal art to the Art Gallery of New South Wales. Elderly Mollie appeared on camera for the ABC's 7.00 News, talking about the works she had collected over a lifetime.

"Mollie Gowing is a very rare and unconventional person, and that's borne out in the nature of her gift," said one gallery staffer.

Gowings closed its doors for the last time in January having traded for 138 years. Obviously they couldn't keep up with the times. It's a bit sad. I bought some pants and a work shirt at Gowings about two years ago, and they have both worn very well. After trying to trade on their reputation for some years, the value of the brand faded to very little indeed.

Mollie's gift looks set to endure well into the future. She'll be remembered at the gallery for a very long time. Hopefully, the bequest will be commemorated on the labels used to describe the paintings and other works, which include some woven items that her husband sent to her from the Top End while he was serving with the Australian military.

"Mollie Gowing is a very rare and unconventional person, and that's borne out in the nature of her gift," said one gallery staffer.

Gowings closed its doors for the last time in January having traded for 138 years. Obviously they couldn't keep up with the times. It's a bit sad. I bought some pants and a work shirt at Gowings about two years ago, and they have both worn very well. After trying to trade on their reputation for some years, the value of the brand faded to very little indeed.

Mollie's gift looks set to endure well into the future. She'll be remembered at the gallery for a very long time. Hopefully, the bequest will be commemorated on the labels used to describe the paintings and other works, which include some woven items that her husband sent to her from the Top End while he was serving with the Australian military.

George Gittoes -- talented, committed, brave, inventive, enterprising -- has just released in Australia his new film, Rampage. The idea came to him during the filming of his previous movie, Soundtrack To War, which chronicled the musical activities or U.S. service men and women on operations in Iraq. That was a wonderful film. During filming, he was confronted by the fact that one of his subjects, Elliott Lovett, came from a place in America so savage that Iraq could be considered a way out of trouble. Today's The Daily Telegraph covered the new release in its 'Sydney Live' supplement (here's an earlier story in the same tabloid).

Brown Sub, as the housing project is called, is somewhere you don't want to go. It is drug-ridden, gang-infested, systematically violent, and almost impossible to escape if you are a resident.

Located in Miami, Florida, the Brownsville Subdivision is home to Lovett, and he takes Gittoes into the area, introduces the filmmaker to his family, and shows him around the traps.

[G]oing to Brown Sub with Lovett, Gittoes was to awaken to the nightmare which is the project dwellers' reality. He filmed interviews on the street and in gang headquarters, living the experience and earning the trust of a cast of extraordinary characters who spoke, rapped, cried and raged directly into Gittoes' lens. "I discovered with Rampage that the real job of the director is to get the best performance out of the 'actors'. Rampage is wall-to-wall performances," Gittoes says.

I remember seeing Soundtrack To War when it first came out and being really very impressed with it. There was a distinct charm to the performances by the soldiers and Iraqis who were filmed on location in the middle of what is now a struggle fought over more days and weeks than World War Two. Gittoes has a unique ability to get people to reveal themselves. As the Telegraph's Elizabeth Fortesque writes:

He is non-judgemental about everyone on whom he trains his camera, living entirely in the moment and seeing the world from their perspective.

In the battle between personal fear, and fear of "not having a film", Gittoes says the latter won out.

Great line. Great sentiment. The work is everything.

The blogerati brawl continues, with a new post on MetaxuCafe, and plenty of new comments in Susan Wyndham's Undercover blog. Following my own contribution, however, I thought I'd introduce dunkleosteus terrelli to be the mascot for the literary pundits.

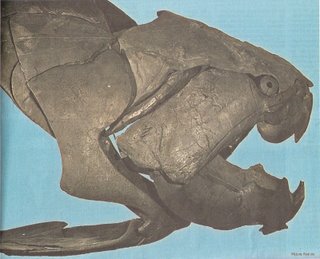

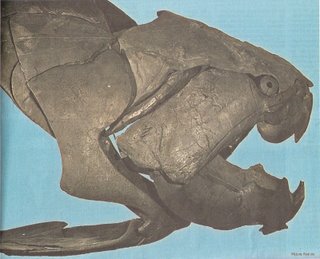

Dunkleosteus appeared in two newspaper articles published today. The picture above appeared alongside the story running under the headline 'The strongest jaws in history', in the online version (it's different in the printed version) of The Australian. There's another picture if you click on the link. A picture also appears with the story under the headline 'Monster fish crushed opposition with strongest bite ever' in The Sydney Morning Herald, and which contains this:

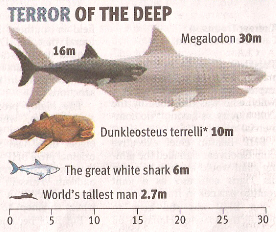

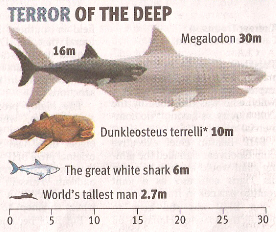

The Australian's story has an illustration showing the relative sizes of various sea-dwelling creatures (including humans).

According to The Australian, the pressure generated by a woman wearing a stiletto heel of 0.5cm area, by stepping on the toe of her husband would be about 127kg per square metre. The pressure brought to bear on its prey by dunkleosteus' jaws was 5000kg per square metre. Clearly, it's better to be trodden on just before heading out for dinner or to a night at the opera, than meeting up with dunkleosteus. Not much of a comparison, in fact. You'd be ripped in half before you knew what was happening. From the printed version of The Australian's story:

According to The Australian, the pressure generated by a woman wearing a stiletto heel of 0.5cm area, by stepping on the toe of her husband would be about 127kg per square metre. The pressure brought to bear on its prey by dunkleosteus' jaws was 5000kg per square metre. Clearly, it's better to be trodden on just before heading out for dinner or to a night at the opera, than meeting up with dunkleosteus. Not much of a comparison, in fact. You'd be ripped in half before you knew what was happening. From the printed version of The Australian's story:

Well, we know what happened to dunkleosteus and T-rex, don't we?

Dunkleosteus appeared in two newspaper articles published today. The picture above appeared alongside the story running under the headline 'The strongest jaws in history', in the online version (it's different in the printed version) of The Australian. There's another picture if you click on the link. A picture also appears with the story under the headline 'Monster fish crushed opposition with strongest bite ever' in The Sydney Morning Herald, and which contains this:

Dunkleosteus was the first known large predator, pre-dating the dinosaurs. It belonged to a diverse group of armoured fish, placoderms, that dominated the oceans in the Devonian period between 360 million and 415 million years ago. Its formidable bite allowed it to feast on other armoured aquatic animals, including primitive sharks and smaller creatures protected by bone-like casings.

The Australian's story has an illustration showing the relative sizes of various sea-dwelling creatures (including humans).

According to The Australian, the pressure generated by a woman wearing a stiletto heel of 0.5cm area, by stepping on the toe of her husband would be about 127kg per square metre. The pressure brought to bear on its prey by dunkleosteus' jaws was 5000kg per square metre. Clearly, it's better to be trodden on just before heading out for dinner or to a night at the opera, than meeting up with dunkleosteus. Not much of a comparison, in fact. You'd be ripped in half before you knew what was happening. From the printed version of The Australian's story:

According to The Australian, the pressure generated by a woman wearing a stiletto heel of 0.5cm area, by stepping on the toe of her husband would be about 127kg per square metre. The pressure brought to bear on its prey by dunkleosteus' jaws was 5000kg per square metre. Clearly, it's better to be trodden on just before heading out for dinner or to a night at the opera, than meeting up with dunkleosteus. Not much of a comparison, in fact. You'd be ripped in half before you knew what was happening. From the printed version of The Australian's story:By comparison, scientists estimate the bite of Tyrannosaurus rex to have had a force of about 1360kg.

Well, we know what happened to dunkleosteus and T-rex, don't we?

Wednesday, 29 November 2006

Susan Wyndham's post on Undercover is titled 'The power of the blogerati'. It's a good one, and follows the recent "brawl" (her term) that exploded in the blogosphere after "an opinion piece [appeared] in London's Telegraph by British literary critic John Sutherland, who deplores the damage done by sloppy online book reviewers".

Sutherland wrote against book reviews by bloggers, then Susan Hill blogged for them, then Rachel Cooke in an article titled 'Deliver us from these latter-day Pooters' "handed out slaps to both Sutherland and Hill", says Wyndham. From Cooke's article:

The Literary Saloon at the complete review was outraged by Cooke's attitude toward blogging reviewers (or reviewing bloggers — take your pick). One of those who she mentioned during her trawl through the balmier regions of the blogosphere (I'm showing my preferences here, I know), Kimbofo of Reading Matters, posted about it. She then posted again about a voluntary code of practice that is being mooted in Britain.

Simultaneously, in Australia, Tim Sterne posted on Sarsaparilla a hilarious monologue that fully takes the measure of 'official' intellectuals such as Sutherland and Cooke.

Sterne's tongue-in-cheek piss-take sums it all up nicely, and we wonder how much longer will be the legs on this particular critter that is scuttling, back and forth, across the blogosphere. As I sit here typing on my pine-wood desk I can reach out and pick up a can of Mortein's 'Insect Seeking' fly-spray ("kills fast", "odourless", "low-irritant"). With writers like Sterne on the watch, there's no need to pick it up. Once read, twice shy.

Wyndham's final word? "The solution is to read critically, even when you're reading reviews."

Sutherland wrote against book reviews by bloggers, then Susan Hill blogged for them, then Rachel Cooke in an article titled 'Deliver us from these latter-day Pooters' "handed out slaps to both Sutherland and Hill", says Wyndham. From Cooke's article:

Although Professor Sutherland is a very distinguished academic, lately his work has felt rushed and lazy. As at least one reviewer pointed out, his most recent book, How To Read a Novel: a User's Guide, is leprous with misquotations. As for Susan Hill, she has an output so prodigious it is practically incontinent. Look at her website if you don't believe me.

The Literary Saloon at the complete review was outraged by Cooke's attitude toward blogging reviewers (or reviewing bloggers — take your pick). One of those who she mentioned during her trawl through the balmier regions of the blogosphere (I'm showing my preferences here, I know), Kimbofo of Reading Matters, posted about it. She then posted again about a voluntary code of practice that is being mooted in Britain.

Simultaneously, in Australia, Tim Sterne posted on Sarsaparilla a hilarious monologue that fully takes the measure of 'official' intellectuals such as Sutherland and Cooke.

Then, one day, normal people started doing their own thinking and the two-tiered system of thinkers and thinkees began to crumble. At first professional thinkers laughed at these “amateurs”; non-professional thinking was “just a fad”, they reassured one another, and besides, people aren’t stupid, they know that when it comes to thinking you can only rely on the professionals. But the professional thinkers were wrong, and now non-professional thinking is threatening the status quo - and we professional thinkers don’t think much of that at all.

Sterne's tongue-in-cheek piss-take sums it all up nicely, and we wonder how much longer will be the legs on this particular critter that is scuttling, back and forth, across the blogosphere. As I sit here typing on my pine-wood desk I can reach out and pick up a can of Mortein's 'Insect Seeking' fly-spray ("kills fast", "odourless", "low-irritant"). With writers like Sterne on the watch, there's no need to pick it up. Once read, twice shy.

Wyndham's final word? "The solution is to read critically, even when you're reading reviews."

Margot McKay is to appear before the Supreme Court on 2 February. I like the headline in the 'Business' section of The Sydney Morning Herald best: "Pokies flack charged". But the story by Kate McClymont on page 3 of the front section is also worth reading:

This seems to be just as bad as what Steve Vizard did, but because she's just a PR operative, it gets stuck in the corner of page 3, instead of up there in lights on the front page. Both cases are appalling. "Oh, the irony," moans reporter Michael Evans in the 'Business' section,

It seems like corruption at the gaming-machine manufacturer, Aristocrat, is endemic. It'll be interesting to see if she gets banned from being employed in her profession for 10 years, as Vizard did.

According to the Crown statement handed to the magistrate, Geoff Bradd, at the Downing Centre Local Court yesterday, McKay used her son, Nicholas, her mother, Cecilia, and a family friend, Jennifer Holt, to buy almost $150,000 of Aristocrat shares in August and October 2004, before announcements to the stockmarket that McKay herself had written.

This seems to be just as bad as what Steve Vizard did, but because she's just a PR operative, it gets stuck in the corner of page 3, instead of up there in lights on the front page. Both cases are appalling. "Oh, the irony," moans reporter Michael Evans in the 'Business' section,

McKay was hired to help restore the company's image after allegations of fraud at executive level.

It seems like corruption at the gaming-machine manufacturer, Aristocrat, is endemic. It'll be interesting to see if she gets banned from being employed in her profession for 10 years, as Vizard did.

H. G. Wells and Winston Churchill had a lot in common. According to a story by Steve Meacham on page 3 of today's The Sydney Morning Herald, Churchill (1874 - 1965) read everything Wells (1866 - 1946) wrote:

Churchill's magisterial tome History of the English-Speaking Peoples was similarly based, in its concept at least, on an idea of Wells'.

Both men would have been intrigued by the 'Coalition of the Willing' — a phrase the leaders of the United States, the United Kingdom and Australia never use nowadays, of course — as it would have seemed a living reference pointing in the same direction. The size of the invasion force? U.S.: 250,000 troops, U.K: 45,000 troops, Australia: 2,000 troops. But then there was also South Korea (3,300 troops) which sort of demolishes my notion, doesn't it.

Churchill also used Wells' words in his speeches. Dr Richard Toye, a history lecturer at Cambridge University, says of Churchill's predilection:

The two men met in 1902 after Churchill - then an emerging politician - wrote a long letter to Wells saying, "I read everything you write."

Churchill's magisterial tome History of the English-Speaking Peoples was similarly based, in its concept at least, on an idea of Wells'.

Both men would have been intrigued by the 'Coalition of the Willing' — a phrase the leaders of the United States, the United Kingdom and Australia never use nowadays, of course — as it would have seemed a living reference pointing in the same direction. The size of the invasion force? U.S.: 250,000 troops, U.K: 45,000 troops, Australia: 2,000 troops. But then there was also South Korea (3,300 troops) which sort of demolishes my notion, doesn't it.

Churchill also used Wells' words in his speeches. Dr Richard Toye, a history lecturer at Cambridge University, says of Churchill's predilection:

"It's a bit like Tony Blair borrowing phrases from Star Trek or Doctor Who."

Tuesday, 28 November 2006

The first feature film to be made, ever, The Story of the Kelly Gang, has been (partly) rejuvenated. Archivists have put together 18 minutes of the film. When it was made it was much longer, at a time when films generally ran for no more than twenty minutes.

The Sydney Morning Herald covered the story last Friday. Tonight, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation's 7.30 Report ran a story about it. The Web site now contains a complete transcript of the piece, by reporter Ben Knight.

"With the Story of the Kelly Gang we see the beginnings of a film grammar," says Graham Shirley, a senior curator at the National Film and Sound Archive, who was interviewed for the show, among others.

One archivist found seven minutes of film in a British archive just by doing a Web search. Other footage appeared in a garbage dump and during a house renovation. Reconstruction of the badly-damaged footage was performed in Australia and Amsterdam.

It'll be interesting to see what sort of coverage this will receive in the broadsheets in two days' time. Ned Kelly has captivated Australians for over a hundred years, since he was hanged in 1880, and even before. "In the time since his execution," says the Wikipedia, "Ned Kelly has been mythologized among some into a Robin Hood figure of sorts, a political revolutionary and a figure of Irish Catholic and working-class resistance to the establishment and British colonial ties."

When the original hour-long film, directed by Charles Tait and costing £1000, was first shown at the Melbourne Town Hall on December 26, 1906, it created a sensation.

The Sydney Morning Herald covered the story last Friday. Tonight, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation's 7.30 Report ran a story about it. The Web site now contains a complete transcript of the piece, by reporter Ben Knight.

"With the Story of the Kelly Gang we see the beginnings of a film grammar," says Graham Shirley, a senior curator at the National Film and Sound Archive, who was interviewed for the show, among others.

One archivist found seven minutes of film in a British archive just by doing a Web search. Other footage appeared in a garbage dump and during a house renovation. Reconstruction of the badly-damaged footage was performed in Australia and Amsterdam.

To mark the film's 100th anniversary, a digitally enhanced version of the 18 minutes rescued from oblivion will get its own world premiere in Canberra next Thursday.

It'll be interesting to see what sort of coverage this will receive in the broadsheets in two days' time. Ned Kelly has captivated Australians for over a hundred years, since he was hanged in 1880, and even before. "In the time since his execution," says the Wikipedia, "Ned Kelly has been mythologized among some into a Robin Hood figure of sorts, a political revolutionary and a figure of Irish Catholic and working-class resistance to the establishment and British colonial ties."

Schapelle Corby "may see no cash from book" reports The Sydney Morning Herald. It's only a tiny piece in the domestic 'News Focus' section (p. 5), so I'll quote it in full.

The West Australian has a longer version of the same story, which it published on 13 November.

Wikipedia has a compendious treatment of the saga, if you're curious about this former fashion student who has been convicted, by an Indonesian court, of attempting to import into Indonesia, hidden inside her boogie-board case, several kilos of marijuana. Last year she was imprisoned in Bali for twenty years. The book itself is being flogged by ABC bookshops as well as everyone else in the country. It was written by Kathryn Bonella. This from the 10 November edition of The Daily Telegraph, a tabloid, which I never read (well, almost never: I did buy the two Sunday papers last weekend, but only because I wanted fresh news about the Victorian elections):

Eminently missable.

The convicted drug smuggler Schapelle Corby, 29, may make a lot of money from her book, but she may never see any of it. The Minister for Justice, Chris Ellison, confirmed yesterday that proceeds from sales of the book, My Story, could be confiscated under Commonwealth proceeds from crime legislation.

The West Australian has a longer version of the same story, which it published on 13 November.

Wikipedia has a compendious treatment of the saga, if you're curious about this former fashion student who has been convicted, by an Indonesian court, of attempting to import into Indonesia, hidden inside her boogie-board case, several kilos of marijuana. Last year she was imprisoned in Bali for twenty years. The book itself is being flogged by ABC bookshops as well as everyone else in the country. It was written by Kathryn Bonella. This from the 10 November edition of The Daily Telegraph, a tabloid, which I never read (well, almost never: I did buy the two Sunday papers last weekend, but only because I wanted fresh news about the Victorian elections):

Based on a series of secret interviews Bonella conducted with Corby inside the jail, the Pan Macmillan book provides a frightening glimpse of the squalid conditions inside the jail.

Eminently missable.

Ian McEwan has been accused of plagiarism, reports Ben Hoyle in The Australian today (p. 13). And it's not the first time it's happened.

Ian McEwan has been accused of plagiarism, reports Ben Hoyle in The Australian today (p. 13). And it's not the first time it's happened.The newspaper has exerpted passages from McEwan's 2001 novel, Atonement, which was shortlisted for the Booker Prize of that year, as well as others from a book written by Lucilla Andrews and published in 1977, No Time For Romance. After reading the excerpts, it looks like there is some merit in the accusation. But Atonement is a long novel, reaching 372 pages in my edition, and a few snipped quotes from here and there should not overly trouble readers. It is unlikely that this accusation will carry further than this article, which was published in The Times yesterday.

McEwan is dismissive of the claims of plagiarism:

"When you write a historical novel you do depend on other writers. I have spoken about Lucilla Andrews countless times ... It has always been a very open matter."

But the excerpts provide some compelling proof. This is from Atonement:

"... she had already dabbed gentian violet on ringworm, aquaflavine emulsion on a cut, and painted lead lotion on a bruise ..."

And this is from No Time For Romance:

"Our 'nursing' seldom involved more than dabbing gentian violet on ringworm, aquaflavine emulsion on cuts and scratches, lead lotion on bruises and sprains."

In the 10 lines of acknowledgements found at the end of Atonement, McEwan in fact names No Time For Romance as a source for his novel ("I am also indebted to the following authors and books..."). So it's a bit of a storm in a teacup. I'm almost embarrassed for having detailed this much.

But Natasha Alden, a student at Oxford University, who wrote a thesis on war fiction, and had read Andrews' book, obviously thought it worth informing Andrews, who died a month ago. Andrews' agent, Vanessa Holt, "said she had found McEwan's behaviour discourteous and disappointing":

"She wasn't approached for permission to use her autobiography. I think she would have been very happy to have been consulted."

I remember being impressed with Atonement when I read it, but today, confronted with this piece in my daily broadsheet, I couldn't for the life of me recall the plot. I did remember something about a girl whose lies cause pain to people around her. I also recall that she eventually felt shame at the memory. There are scenes in a hospital, that I do remember, and others in the fields of war. There's also a man who is a bit of a bore who does well in chocolate, if I remember correctly. There are many things that I forget.

Monday, 27 November 2006

Susan McCulloch is proud of her father's achievement: publishing, in 1968, The Encyclopedia of Australian Art. New editions appeared in 1984 and 1994. Now, reports Angela Bennie on page 11 of The Sydney Morning Herald, the fourth edition has been compiled by McCulloch and her daughter, Emily McCulloch Childs.

Aboriginal art has been given its own section in the book, which includes 8000 listings, 1500 new entries and 1000 illustrations. Says Susan:

The New McCulloch's Encyclopedia of Australian Art is published by Aus Art Editions in association with Miegunyah Press, which is a well-known publisher of art books and a special imprint of Melbourne University Publishing. My edition of Juan Davila by Guy Brett and Roger Benjamin is published by Miegunyah.

Aboriginal art has been given its own section in the book, which includes 8000 listings, 1500 new entries and 1000 illustrations. Says Susan:

"Just take the interest and activity there is around Aboriginal art. It has simply exploded."

"We decided to give Aboriginal art its own section after much thought," Susan says. "This was not meant to segregate it, but we felt it would be more useful as a reference work that way. One day it will merge, I believe, but it should not be merged now … we are reflecting how things are, where Aboriginal art is. In all our major institutions like galleries, they are included but within their own space or in a gallery of their own. So it is in the book."

The New McCulloch's Encyclopedia of Australian Art is published by Aus Art Editions in association with Miegunyah Press, which is a well-known publisher of art books and a special imprint of Melbourne University Publishing. My edition of Juan Davila by Guy Brett and Roger Benjamin is published by Miegunyah.

Sunday, 26 November 2006

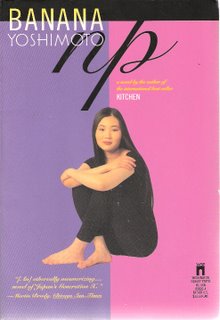

Review: N.P., Banana Yoshimoto (1995)

Review: N.P., Banana Yoshimoto (1995)In this deliriously sexy little novel, we find a whole world of delights that fulfill and satisfy our craving for fictional indulgence. Summer in Tokyo: the heat, the sweat, the nights drinking tea on the pavement, the trucks rumbling past on the busy road.

But we also find ourselves mixed up with a curiously intimate bunch of young people who are struggling to find themselves in the world. Kazami, the narrator, had seen Otohiko and Saki once before, many years earlier, when she was a high-school student and in love with Shuji. It was at a special event in one of those ritzy central-Tokyo function rooms. The brother and sister were standing together smiling, laughing. Kazami has never forgotten, and one day, years later, when she is on lunch break from her work at the university, she spies Saki in the street and introduces herself.

She discovers that Otohiko is in love with his half-sister, Sui, who had been the lover of her own father back in Boston, where the siblings grew up. Sarao Takase, the writer who made love to his own daughter, wrote a collection of ninety-seven stories, N.P., and the young people are wondering about the ninety eighth, which Shuji was translating into Japanese when he committed suicide. Otohiko and Sui believe this story is cursed.

But the muddle of the plot is the least wonderful thing about this novel. More important is the directness of Japanese peoples' interactions, the clashes and revelations that emerge, especially among a group of young people, like this, who are brought together by the strange facts surrounding Takase's work and life. They have inherited a lot of baggage, and are eager to find a way to deposit it somewhere. We worry that Kazami will be hurt by them. Strangeness pervades the novel like weeds in an untended garden.

Kazami, for her part, is a confident young woman. But she has her own demons. Her mother and father separated when she was a girl, and now he drinks and she continues to lecture her. She can't see herself living with either. She also has thoughts about Shuji, dead for many years, but still present: Sui had had an affair with him.

When you've fallen in love, broken up, lost a loved one, and start getting older, everything seems the same. I couldn't tell what was good and what was bad, what was better and what was worse. I simply didn't want to have any more bad memories. I wished that time would stop, and summer would never come to an end. I felt very vulnerable.

Little nuggets and jewels of wisdom like this pepper the narrative. Here's Sui:

"You know, I never have really had any friends. There were a lot of girls who I hung out with, but never anyone who I could talk with like this. I could talk with Otohiko, but he's the only other one."

"He's the man," I said. "Maybe that's why you were the perfect pair. You could complain, and talk about your doubts and still keep on going."

That's how most couples made a go of it anyway.

In a gap in the conversation that Kazami and Otohiko are having, Kazami contemplates her own mortality:

It started raining. I could hear the faint, dark sound through the open window. The melancholy that accompanies the night swept in and filled the room. It coldly watches those of us who dwell in our bodies as we struggle through the day. The shadow of death. The feeling of powerlessness that sneaks up on you when you're not watching; the desolation that will swallow you up if you let down your guard.

The erotic tinge, the bright, insistent sparkle of the prose, the strangeness of foreign-raised young Japanese people, and the heavy mystery surrounding those stories, combine in this short, thrilling little book to provide a terrific reading experience.

Review: A Civil Action, Jonathan Harr (1995)

Review: A Civil Action, Jonathan Harr (1995)Early in this piece of literary journalism a lawyer is walking down a central Boston street. He is quite famous, having been depicted in a movie about a case he had led. This is cute, as A Civil Action itself was made into a movie, starring John Travolta. Reality mimics reality. A mirror is held up to the book, and it stares back, hard-nosed and powerful. Courtroom drama plays tag with big financial settlements in our mind’s eye. The downtrodden, the neglected, the abused are redeemed by the due process of the law. It is a stirring and engaging scene. Almost.

It is an intriguing book. In this day and age, when the connection between industrial solvents and cancer is well-established, the mystification of doctors, and the slowness of the reaction to multiple cases of leukaemia in a single, small Massachusetts town, is itself something of a puzzle for us.

We feel sorry for Jan Schlichtmann, of course, as he is, at the beginning of the book, out of cash and in serious debt. But his spending patterns give us no confidence in his fiscal judgement. The Porsches are clearly not necessary. The battler families of Woburn earn our commiseration. They are the ones who suffered. Schlichtmann shouldn’t really be the point of the story. But he is. The ostensible point of the story is environmental pollution: a media trope now so well developed that we barely register it when we skim through the daily newspapers.

In those days, however, connections between leukaemia (a blood cancer) and industrial chemicals was a new thing. The book took eight years to write. Published eleven years ago, it forces us to make allowances for the passage of time, and for the significant developments in public consciousness that have occurred thereby.

The plot builds steadily, over decades, from the time of the onset of disease in one child, to death, from the beginning of the court process to the emergence of multiple legal representatives. The evidence supplied by eminent experts goes hand in hand with legal wrangling brought by the defendant’s lawyer, a scruffy villain by the name of Cheeseman. There’s Facher, a rough, slightly cantankerous older lawyer who teaches at the Harvard Law School and makes young female students cry. Schlichtmann stands apart, aiming high, looking toward the big settlement.

All of this is, of course, true. It really happened. And so while we study the development of the plot we are also conscious of the emergence of public perceptions that have led to where we stand today, in the twenty-first century, atop a massive pile of precedent and received knowledge. This case has contributed to making us what we are.

Saturday, 25 November 2006

Author Kate Legge's story on pp. 20 - 25 of this weekend's issue of The Weekend Australian Magazine answers a lot of questions about the low recognition factor plaguing the governor-general of Australia. The Queen's representative, and the man who signs bills into law, has taken a back seat in the running of the country. Whereas the prime minister, John Howard, injects issues into all sorts of national debates, Jeffries' "social conservatism and hyper-caution" leave him with fewer outlets for his energies.

Author Kate Legge's story on pp. 20 - 25 of this weekend's issue of The Weekend Australian Magazine answers a lot of questions about the low recognition factor plaguing the governor-general of Australia. The Queen's representative, and the man who signs bills into law, has taken a back seat in the running of the country. Whereas the prime minister, John Howard, injects issues into all sorts of national debates, Jeffries' "social conservatism and hyper-caution" leave him with fewer outlets for his energies."Imagination is a huge issue," says a former state governor familiar with the trials of constitutional office. "You have to imagine yourself into these positions. There is an element of magic in the way you inspire people."

Only two per cent of Australians can recall his name, it appears. But Michael Jeffries, who is endeavouring to "steady things down" after the debacle with Peter Hollingworth, his predecessor in the vice-regal role, refuses to "be up there competing with PMs and ministers."

"The intention is not for self-aggrandisement; the intention is to show the Australian people that their G-G is out there doing a job of worth."

But that won't cut it with the media, and Jeffries thinks it's the media who have the problem.

"I think there is a media responsibility to report periodically what the Governor-General is doing ... that's where I get disappointed. There isn't the depth of examination, except if you make a mistake. Trip over something — wrong word, wrong phrase — bang, you're gone. We've had very, very little coverage, which I find amazing, quite frankly."

These frustrated people always blame the media. It's a constant refrain. Anything you don't like in the way of publicity and it's the media's fault. This kind of knee-jerk reaction doesn't reflect well on a man who wants to improve his public profile. It makes him look small and bitter. Hardly the kind of image you'd want to encourage. But Jeffries has nothing better to say. He wants to have his cake and eat it, too. He wants to be low-profile so he doesn't upstage the real powers in the land, but he wants his "'Honesty. Integrity.'" to be spread across the broadsheets and the tabloids.

As if. But I think, at least, that Legge does a good job in this profile.

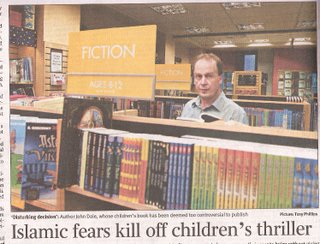

Lyn Tranter, John Dale's literary agent, says it's "censorship by salesmen". The Weekend Australian reports that Dale's new book, Army of the Pure, has been cancelled by the publisher, Scholastic Australia, because they fear angering Muslims. A young adult title, the book was due to be published soon. Dale is furious.

Scholastic's general manager, publishing, Andrew Berkhut, said the company had canvassed "a broad range of booksellers and library suppliers", who expressed concern that the book featured a Muslim terrorist.

The anxiety is understandable, considering the pasting Danish consulates received in the aftermath of the cartoons scandal. Muslims in Australia have been under pressure lately after the mufti of Australia, Sheikh Taj el-Din al-Hilaly, likened normally-dressed Western women to "uncovered meat" that the cats would get at if left outside in the garden. The Hilaly scandal has died down in the media, for the moment, but it is easy to imagine Muslims protesting a book title that slurred them, in today's atmosphere of fear and distrust.

Friday, 24 November 2006

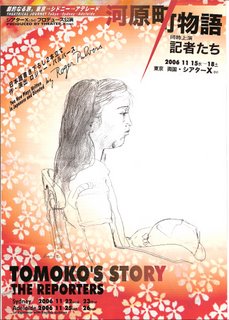

Event: Tomoko's Story, The Reporters, Roger Pulvers (writer/director), Parade Studio, NIDA

Event: Tomoko's Story, The Reporters, Roger Pulvers (writer/director), Parade Studio, NIDATightly scripted, these plays are a delight. So tightly scripted that, having imbibed three beers before the performance and at interval, I had to duck out to relieve myself near the end of the second performance — Tomoko's Story — and missed some key action.

But I enjoyed myself immensely. With a big grin of my face, I guffawed as Yutaka Nagahata, playing Pedro in The Reporters and Hidetaro in Tomoko's Story, clowned dyspeptically about the stage. The surtitles came in handy, even for me. But it was the living, breathing essence of Japanese that I enjoyed so much. Pulvers is a very talented writer.

The Reporters is a comic piece with dark edges that features two reporters in a tin-pot Central- or South-American state who are caught up in a revolution. But the action is in their political affiliations. Mary, played by Koko Furuta, is an American reporter who writes for a right-wing newspaper, but actually sympathises with the Communists. Li Gung Ho, played by Kenjiro Otani, is a Chinese reporter who actually likes the capitalist way of life. They knew each other before meeting, here, in a little cafe hosted by the taciturn Pedro. Inspired by their own duplicity, they each decide to write a piece for the other. Their productions are complimented by the head offices. Finally, throwing caution to the wind, they decide to swap lives, houses, everything. Li-san wants to live near Disney World in Florida. Mary is looking forward to meeting up with her boyfriend in Beijing.

Tomoko's Story is more complex and darker. The edges in this piece are brightened by Nagahata, who masterfully plays the 'master' of a little coffee shop in Kyoto called 'Island'. Avuncular and with a shadowy past, Hidetaro hosts the meeting of Tomoko and Frank, a GI on R&R from Vietnam. Tomoko is a student who doesn't go to classes, and whose most precious possession is a signed copy of a book by William Faulkner, that the writer had presented to her when she was a girl. Frank swears by his St Christopher medal. He persuades Tomoko to exchange treasures with him. He also gives Hidetaro modern pop music records, and Tomoko a portrait of James Dean.

But Tomoko is never at ease with Frank. She's a cagey one, and resents this intrusion on her personal space. She also carries some heavy emotional baggage. As a girl, she had gone to Illinois to school, and recalls the bullying she endured at the hands of white kids, because of her race. At Island, she finds peace, and the impersonal friendship of the master, Hidetaro, is congenial to her.

Frank is looking for something. Unfortunately, I missed some important stuff. But the rape changes everything.

There are also two flashbacks, which are handled adroitly. With only three actors on stage, the performance fairly shoots along. With minimal props, the audience is invited to suspend disbelief, and immerse themselves in the poetry of the play. Very memorable.

I left home at 7:00 p.m. and took the M5 motorway out to Kensington. I walked in the theatre doors at 7:30, having parked in High Street, near the entrance to the Australian Jockey Club.

The performance now moves to Adelaide, where it will be staged on Saturday and Sunday at the Hartley Playhouse, University of South Australia. Recommended.

Haruki Murakami thinks the best is yet to come. In an interview with Nick Jones of The Prague Post, Murakami reveals a little more about himself. He does this each time he's interviewed, always in his Tokyo office.

Thanks to Dogmatika for the heads up.

Each book he writes represents a journey inside himself, he says. "I'm just sketching what I saw in the darkness," he says. "Sometimes it's fun, [but] sometimes it's dangerous, so I have to protect myself. That's why I'm running every day. You have to be physically strong to survive that darkness."

Thanks to Dogmatika for the heads up.

Thursday, 23 November 2006

Plagiarism is a plague at university. Lecturers are feeling under siege as students copy and paste bits out of online resources, says Anne Susskind (a former university lecturer) in The Sydney Morning Herald. And that's not all she says.

I've felt this myself. I feel like I actually studied harder when I was an undergraduate, 25 years ago, than I do today. It's as if the lecturers are quarantining the 'pass' grades for international students. Especially in courses offered within the Department of Media and Communications, where I study, and where the focus is on the use of language. International students manifestly struggle.

Susskind quotes Megan Le Masurier, who was my lecturer in first semester, for the 'Making Magazines' unit of study. It was a good course. But one night, when I arrived early (as is my wont), she sighed loudly and said, "It's not English. It's a new language they've invented." I felt for her. Then, in a second semester tutorial I listened along with the other members of my class, for the 'Literary Journalism' unit (lectured by Jose Borghino), as a Chinese student declaimed her inscrutable prose. I could barely understand a word. How these students get into the course in the first place is a mystery to me. An IELTS score of 6.5 — which is what they are required to achieve in order to enter a course at the University of Sydney — is clearly not adequate for such humanities subjects as journalism.

Le Masurier also says about plagiarism that it's a way for the students to 'get back' at a system they feel let down by:

She leaves the door open for the pundits to declare against the federal government, which has been cutting funding to universities steadily, over recent years. If there were more teachers..., she implies that there would be less discontent among students. Possibly.

I always marvel that anyone could even dream of plagiarising. Such a waste of time, it seems to me. You're cheating yourself out of the opportunity to shine. Even if you don't get caught. And new plagiarism detection software being developed makes it more likely as the years pass, that you will.

The anger level of English-as-first-language students is rising as lecturers "dumb down" their teaching for international students, who are left bewildered by the resentment they feel comes from the first-language English speakers...

I've felt this myself. I feel like I actually studied harder when I was an undergraduate, 25 years ago, than I do today. It's as if the lecturers are quarantining the 'pass' grades for international students. Especially in courses offered within the Department of Media and Communications, where I study, and where the focus is on the use of language. International students manifestly struggle.

Susskind quotes Megan Le Masurier, who was my lecturer in first semester, for the 'Making Magazines' unit of study. It was a good course. But one night, when I arrived early (as is my wont), she sighed loudly and said, "It's not English. It's a new language they've invented." I felt for her. Then, in a second semester tutorial I listened along with the other members of my class, for the 'Literary Journalism' unit (lectured by Jose Borghino), as a Chinese student declaimed her inscrutable prose. I could barely understand a word. How these students get into the course in the first place is a mystery to me. An IELTS score of 6.5 — which is what they are required to achieve in order to enter a course at the University of Sydney — is clearly not adequate for such humanities subjects as journalism.

Le Masurier also says about plagiarism that it's a way for the students to 'get back' at a system they feel let down by:

"Plagiarism is a sign of discontent," she says. "They think their teachers are so busy. They want to be noticed and it's almost a testing gesture, a payback, like a response to feeling neglected."

She leaves the door open for the pundits to declare against the federal government, which has been cutting funding to universities steadily, over recent years. If there were more teachers..., she implies that there would be less discontent among students. Possibly.

I always marvel that anyone could even dream of plagiarising. Such a waste of time, it seems to me. You're cheating yourself out of the opportunity to shine. Even if you don't get caught. And new plagiarism detection software being developed makes it more likely as the years pass, that you will.

The ABC will launch a new chat show in an effort to visibly counter claims of bias. Difference of Opinion takes us down the Japanese path of having panels of the usual suspects sit around a table talking 'the issues' to death.

Releasing the station's 2007 schedule, the director of television, Kim Dalton, reveals that Media Watch, the much-criticised media investigative commentary show, will be on again next year. Good. Monday night remains pleasurable. Monica Attard will continue as the program's face and voice. A dry, acerbic one it is, too. Go Monica!

The "veteran journalist" Jeff McMullan will compere Difference of Opinion, which will air for an hour each week. No news yet on what nights it will air. When I telephoned the station they said the scheduling people had left for the day.

Claims of bias against the Australian Broadcasting Corporation have proliferated in recent months. Now we know that the new managing director, Mark Scott, has been busy. (Left-wing bias is, I acknowledge, a permanent feature of the ABC. And it's a bloody good thing that it is, too, as they should always be vigilant, and mindful of the influence on Australian audiences of three commercial, free-to-air stations.)

Releasing the station's 2007 schedule, the director of television, Kim Dalton, reveals that Media Watch, the much-criticised media investigative commentary show, will be on again next year. Good. Monday night remains pleasurable. Monica Attard will continue as the program's face and voice. A dry, acerbic one it is, too. Go Monica!

The "veteran journalist" Jeff McMullan will compere Difference of Opinion, which will air for an hour each week. No news yet on what nights it will air. When I telephoned the station they said the scheduling people had left for the day.

Claims of bias against the Australian Broadcasting Corporation have proliferated in recent months. Now we know that the new managing director, Mark Scott, has been busy. (Left-wing bias is, I acknowledge, a permanent feature of the ABC. And it's a bloody good thing that it is, too, as they should always be vigilant, and mindful of the influence on Australian audiences of three commercial, free-to-air stations.)

Creative writing programs at universities are the odd men out, says John Dale, director of the University of Technology, Sydney's Centre for New Writing.

Creative writing programs should distance themselves from the areas they devolved from — English literature and cultural studies — and align themselves with other creative sectors of universities, such as media and performing arts.

The sector is booming, Dale says.

Well, I'm one of those boomers, it seems. And I agree. Media studies, like creative writing, is an area that offers practical instruction in the art of writing. And the art of thinking, which leads ultimately to personal development. Unlike many other areas of university study, these ones provide an environment where you learn how to make things that are beautiful as well as useful to society.

Society needs, in fact demands, creative individuals.

I'm happy to pay $100-plus an hour to get my creative fix, twice a week. When I get home after class I am energised and fulfilled. I eagerly attack the newspapers and enjoy my free time more than at other times. The impact of the course on my work has also been positive, and I actively seek out opportunities to write things now. I am hoping that the degree will help me to secure a more profitable position in my organisation. Dale says:

IN launching the University of Technology, Sydney's Centre for New Writing in 2004, the novelist and Yale University professor Caryl Phillips referred to the fundamental tension in teaching writing at university when he said that writers are people who put things together while universities are places where you take things apart.

Creative writing programs should distance themselves from the areas they devolved from — English literature and cultural studies — and align themselves with other creative sectors of universities, such as media and performing arts.

The sector is booming, Dale says.

Australian universities now offer more than 70 of these courses. There are numerous mature-age students willing to pay universities $100-plus an hour to sit in a postgraduate writing class.

Well, I'm one of those boomers, it seems. And I agree. Media studies, like creative writing, is an area that offers practical instruction in the art of writing. And the art of thinking, which leads ultimately to personal development. Unlike many other areas of university study, these ones provide an environment where you learn how to make things that are beautiful as well as useful to society.

Society needs, in fact demands, creative individuals.

Richard Florida in Rise of the Creative Class argues that creativity has come to be regarded as the most highly prized commodity in our society, the defining feature of 21st-century economic life.

I'm happy to pay $100-plus an hour to get my creative fix, twice a week. When I get home after class I am energised and fulfilled. I eagerly attack the newspapers and enjoy my free time more than at other times. The impact of the course on my work has also been positive, and I actively seek out opportunities to write things now. I am hoping that the degree will help me to secure a more profitable position in my organisation. Dale says:

When I am asked by my students whether creative writing can be taught, I say no it can't. But it can be learned. The main difference is that the learning process in the workshop environment is interactive, developmental, inspirational, production-based and creative in the true sense.

Wednesday, 22 November 2006

Susan Wyndham, who has been most recently in charge of the Undercover column at The Sydney Morning Herald, has got a new blog.

Undercover struck me as a lot of fun. Every Saturday, I looked forward to reading it. It has news about writers, prizes, and scandals, and general gossip from the world of books here in Australia. Written from the point of view of an insider, Undercover is a must-read.

Wyndham's blog was launched on 17 November, so in announcing it here, now, I'm a tad late. Better late than never.

The blog, which is just one part of the newspaper's online 'Entertainment' Site, will furthermore be home to a book group. Considering the recent launch of the Australian Broadacasting Corporation's First Tuesday Book Club, this seems to be a bit of a trend. To host one online is to tap into the growing appetite among Web surfers for the sort of participatory experience that has made group blogs such as Sarsaparilla and its offshoot the Patrick White Readers' Group so successful. (In fact, Wyndham was quick to pick up on the launch of the latter, and covered it in her column.) The blog's book group post attracted 40 comments.

First up for discussion at Undercover (in its new incarnation) will be a book suggested to Wyndham by Nancy Pearl, who she dubs Seattle's "super librarian". The book is Little Big Man by Thomas Berger. Published in 1999, she says it can be found in "libraries and good bookshops". I wonder. It's presently too late for me to telephone Gleebooks, but I bet it'll be hard for most eager participants out there in the blogosphere to put their hands on. "I will start discussion in a week or so," she said in the 17th. Not really enough time to buy, borrow or steal the book as well as read it. And the week will have ended on Friday. Patrick White Readers' Group gave its participants a month to get sorted, if I remember correctly.

Undercover struck me as a lot of fun. Every Saturday, I looked forward to reading it. It has news about writers, prizes, and scandals, and general gossip from the world of books here in Australia. Written from the point of view of an insider, Undercover is a must-read.

Wyndham's blog was launched on 17 November, so in announcing it here, now, I'm a tad late. Better late than never.

The blog, which is just one part of the newspaper's online 'Entertainment' Site, will furthermore be home to a book group. Considering the recent launch of the Australian Broadacasting Corporation's First Tuesday Book Club, this seems to be a bit of a trend. To host one online is to tap into the growing appetite among Web surfers for the sort of participatory experience that has made group blogs such as Sarsaparilla and its offshoot the Patrick White Readers' Group so successful. (In fact, Wyndham was quick to pick up on the launch of the latter, and covered it in her column.) The blog's book group post attracted 40 comments.

First up for discussion at Undercover (in its new incarnation) will be a book suggested to Wyndham by Nancy Pearl, who she dubs Seattle's "super librarian". The book is Little Big Man by Thomas Berger. Published in 1999, she says it can be found in "libraries and good bookshops". I wonder. It's presently too late for me to telephone Gleebooks, but I bet it'll be hard for most eager participants out there in the blogosphere to put their hands on. "I will start discussion in a week or so," she said in the 17th. Not really enough time to buy, borrow or steal the book as well as read it. And the week will have ended on Friday. Patrick White Readers' Group gave its participants a month to get sorted, if I remember correctly.

Tuesday, 21 November 2006

Japan is contentious for Australians. Culturally, politically, historically, it offers many challenges and little consolation. This was brought home to me by two newspaper articles that appeared in two competing broadsheets this month. They also showed me that front pages can often contain, if not outright falehoods, articles that are adequately rant-like to attract opprobrium.

On 8 November, on the front page of The Australian an article by Stuart Rintoul (described here as "a senior writer") declared that "A sun is rising over Flemington. The Melbourne Cup is being stolen away by raiders from Japan". "It will be remembered as the year the Japanese took the Cup..." he adds. There is some hyperbolic language to soften the fundamentally xenophobic message, but you get it without reading too closely. The article closes with some very strange twists that first of all turn our attention back fifty years to "the signing of the landmark Australia-Japan Agreement on Commerce,"

The basic idea is obvious: memories of the Second World War are evoked and old hatreds fanned by this reporter in an effort to stir up a nationalism that is really very foreign to Australians. Most Japanese people would, furthermore, resent allusions to the Rising Sun, and anyway are too busy paying off the mortgage to entertain militarism in any form whatsoever.

"Australia needn't choose between its history and its geography," said the news announcer on the Special Broadcasting Service (SBS, the multicultural broadcaster) tonight. I didn't catch whether he was quoting a politician (most likely the prime minister, who has just left Vietnam, and the APEC summit). But they did show John Howard, the PM, saying this to the cameras, before he boarded his jet back home:

It'll be interesting to see how The Australian handles this in tomorrow's edition. Front page news? Probably not.

Which brings me to the second article that caught my attention. Written by Deborah Cameron, The Sydney Morning Herald's Tokyo correspondent, the piece, which was published today on page 12, looks at a new, Japanese-language theatre production being staged at the Parade Studio in Kensington, a suburb of Sydney.

There will be "subtitles". I knew that there are subtitles available at the Sydney Opera House during productions, but in this case it had me stumped (until I googled the theatre and discovered it belongs to NIDA — more below). Regardless, the tone of the article, its intent, and its sincerity, are unquestionable.

The writer, Roger Pulvers, admits that the production is a bit of an "experiment". The director of the National Institute of Dramatic Arts (NIDA, which I knew was based in Kensington), Aubrey Mellor, is supportive.

Pulvers also writes newspaper columns (it's not said where they're published, in English or Japanese) and teaches at the Centre for the Study of World Civilisations (no Web site, but it is based at the Tokyo Institute of Technology).

Pulvers pulverises Rintoul. He speaks Russian as well as Japanese. He became an Australian by choice, having been born in the United States of America, "and has translated into Japanese literature from English and Russian". It's not clear exactly what this involves, this translating "into Japanese literature", but the message is clear: here is someone committed to crossing cultural divides, and offering consolation to harried salary earners in both countries. I'm very tempted to go and see this production, to find out what it means to watch a play in Japanese.

If only the Japanese would own up to what happened during World War II. Then we could all (Rintoul included) rest easy. Perhaps.

On 8 November, on the front page of The Australian an article by Stuart Rintoul (described here as "a senior writer") declared that "A sun is rising over Flemington. The Melbourne Cup is being stolen away by raiders from Japan". "It will be remembered as the year the Japanese took the Cup..." he adds. There is some hyperbolic language to soften the fundamentally xenophobic message, but you get it without reading too closely. The article closes with some very strange twists that first of all turn our attention back fifty years to "the signing of the landmark Australia-Japan Agreement on Commerce,"

which cast aside war-time bitterness and recognised that Australia's future prosperity lay with Asia.

The basic idea is obvious: memories of the Second World War are evoked and old hatreds fanned by this reporter in an effort to stir up a nationalism that is really very foreign to Australians. Most Japanese people would, furthermore, resent allusions to the Rising Sun, and anyway are too busy paying off the mortgage to entertain militarism in any form whatsoever.

"Australia needn't choose between its history and its geography," said the news announcer on the Special Broadcasting Service (SBS, the multicultural broadcaster) tonight. I didn't catch whether he was quoting a politician (most likely the prime minister, who has just left Vietnam, and the APEC summit). But they did show John Howard, the PM, saying this to the cameras, before he boarded his jet back home:

We are naturally, and comfortably, and permanently part of this region, and see our future in it.

It'll be interesting to see how The Australian handles this in tomorrow's edition. Front page news? Probably not.

Which brings me to the second article that caught my attention. Written by Deborah Cameron, The Sydney Morning Herald's Tokyo correspondent, the piece, which was published today on page 12, looks at a new, Japanese-language theatre production being staged at the Parade Studio in Kensington, a suburb of Sydney.

When the play, Tomoko's Story, is performed this week in Sydney and Adelaide by its Tokyo cast, the original language will remain. To add a further cross-cultural dimension, the play was written by an Australian with a 39-year attachment to Japan.

There will be "subtitles". I knew that there are subtitles available at the Sydney Opera House during productions, but in this case it had me stumped (until I googled the theatre and discovered it belongs to NIDA — more below). Regardless, the tone of the article, its intent, and its sincerity, are unquestionable.

The writer, Roger Pulvers, admits that the production is a bit of an "experiment". The director of the National Institute of Dramatic Arts (NIDA, which I knew was based in Kensington), Aubrey Mellor, is supportive.

"Typically plays from Japan that come to Australia are either Kabuki or Noh, very exotic and alienating, or really way out with loud music and all sorts of images flying at us," Mellor says.

In reality the bulk of Japanese theatre is "just like ours" — actors telling a story — which is the underlying beauty of Pulvers' newest work, Mellor believes.

Pulvers also writes newspaper columns (it's not said where they're published, in English or Japanese) and teaches at the Centre for the Study of World Civilisations (no Web site, but it is based at the Tokyo Institute of Technology).

Pulvers pulverises Rintoul. He speaks Russian as well as Japanese. He became an Australian by choice, having been born in the United States of America, "and has translated into Japanese literature from English and Russian". It's not clear exactly what this involves, this translating "into Japanese literature", but the message is clear: here is someone committed to crossing cultural divides, and offering consolation to harried salary earners in both countries. I'm very tempted to go and see this production, to find out what it means to watch a play in Japanese.

If only the Japanese would own up to what happened during World War II. Then we could all (Rintoul included) rest easy. Perhaps.

Monday, 20 November 2006

Georg at her blog Stack blogged about it yesterday. What makes these women writers tick? Writer Lionel Shriver fingers Grub Street.

"My flat is strewn with clippings," says Shriver. "I have a special passion for the tiny stories on inside pages that most people overlook." Jane Austen felt the same. She loved reading scandal sheets, and would write about the stories she found there in letters that she sent regularly to members of her family and to friends. These letters, now collected in a single volume, have become her 'clippings'.

In fact, a newspaper story works its way into her fiction, serving as a major plot device in the novel Mansfield Park. We learn, along with poor Fanny (slumming it at her parents' Portsmouth home), that her cousin has fled from the marital domecile with Crawford, the attractive (but too Whiggish) villain of the piece. It is her father who is reading out loud from the paper, which had been borrowed from a friend (poverty prevents him from buying his own copy). Crawford was enthusiastically courting Fanny up to the point when the appalling news breaks. Fanny is shocked, but not jealous: she had another man in mind. Maybe Austen was trying to imagine what it would be like to be embroiled in a society scandal.

"We Need to Talk About Kevin [Shriver's seventh novel, which won the Orange Prize in 2005] is an attempt to imagine what it might be like for me to be a mother," said Shriver during an interview on the ABC's 7.30 Report in September. She says now:

"Nothing I make up will ever top real life," she says. Jane Austen would have agreed.

Peach-coloured sunsets may inspire many an artier writer, but I derive much of my material from black and white.

"My flat is strewn with clippings," says Shriver. "I have a special passion for the tiny stories on inside pages that most people overlook." Jane Austen felt the same. She loved reading scandal sheets, and would write about the stories she found there in letters that she sent regularly to members of her family and to friends. These letters, now collected in a single volume, have become her 'clippings'.

In fact, a newspaper story works its way into her fiction, serving as a major plot device in the novel Mansfield Park. We learn, along with poor Fanny (slumming it at her parents' Portsmouth home), that her cousin has fled from the marital domecile with Crawford, the attractive (but too Whiggish) villain of the piece. It is her father who is reading out loud from the paper, which had been borrowed from a friend (poverty prevents him from buying his own copy). Crawford was enthusiastically courting Fanny up to the point when the appalling news breaks. Fanny is shocked, but not jealous: she had another man in mind. Maybe Austen was trying to imagine what it would be like to be embroiled in a society scandal.

"We Need to Talk About Kevin [Shriver's seventh novel, which won the Orange Prize in 2005] is an attempt to imagine what it might be like for me to be a mother," said Shriver during an interview on the ABC's 7.30 Report in September. She says now:

The book on which I will soon embark took its inspiration from an article in the New York Times about middle-class American families with health insurance who are being literally bankrupted by co-payments and drug charges when major illness strikes. That article broke my heart, which made me think I could constructively break my readership's heart if I could bring such a tale to life.

"Nothing I make up will ever top real life," she says. Jane Austen would have agreed.

Sunday, 19 November 2006

Review: Dark Roots, Cate Kennedy (2006)

Review: Dark Roots, Cate Kennedy (2006)Cate Kennedy writes deftly. Her stories, like Patrick White’s, talk about society, about self-actualisation, and about finding a balance between the personal and the communal, each of which phases of existence has its own demands and imperatives. And there is a great variety of voices in this collection. Each story has its own weight and heft, like a well-made knife. They cut through the reader’s memories and aspirations, and leave a clean mark. They’re terrific. They help you see things more clearly.

On 11 October, Henry Rosenbloom, Kennedy’s publisher at Scribe Publications, a Melbourne-based outfit, blogged about his visit to the Frankfurt Book Fair. During his visit, he sold North American rights for Dark Roots (as well as those for her upcoming novel) to Grove/Atlantic. UK and Commonwealth rights were sold to Atlantic Books. “And suddenly,” he says,

everyone I met seemed to be talking about or wanting to know about ‘the wonderful Australian writer, Cate Kennedy’

It is no myth. She is wonderful. Wonderful and entirely approachable. Her short stories are very short, and they envelop you effortlessly. You slide into them like pulling on comfortable shoes. You are immediately engrossed in their rip and rhythm.

I was engrossed when I read the country story ‘Cold Snap’ in The New Yorker about a boy who catches rabbits and a city blow-in who kills trees. Within a few days I’d driven over to Gleebooks, and found the book on top of the shelf at the left-hand side of the shop, as you enter via the front door. There was a whole stack of them there. I wonder if they’ve gone now.

In September, Stephanie Bishop reviewed Dark Roots in The Sydney Morning Herald and Delia Falconer reviewed it in the Australian Book Review. Kennedy’s also been interviewed by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. She’s an up and coming player, and she deserves it. The questions I’d like to ask her! Such as: whose hand print is on the cover of the collection?

The stories, in brief, are outlined below.

‘Habit’ — a woman is returning to Australia from Columbia. She has cancer. She has bought a lot of cocaine with her superannuation. She has to get through customs. She is nervous. A little thriller of a story. She watches the customs officer unwrap the ceramic statues — three of them — that are covered in newspaper and contain the coke.

‘Flotsam’ — we struggle to work out if it’s a man or a woman, young or old. Time seems to disappear.

Time slides around also in ‘A Pitch Too High for the Human Ear’ as a man’s marriage slowly crumples under the stresses of quotidian life. The dog seems to hold the family together:

Now he takes off down the street and I stop at the end to rest a stitch that feels like a deep knot in my gut pulling upwards, and I jog to the oval and see Kelly trotting slowly to the incline on the far side. I am forty-two years old and the kind of guy who once scored 174 baskets in a season but now gives his wife a StaySharp knife for Christmas, who can barely jog two kilometres, who can never think of what to say, and none of it really hits me until I whistle to watch Kelly bolting back down across the grass and he doesn’t come.

Life is under stress, too, in ‘What Thou and I Did, Till We Loved’, the title taken from a Donne poem. Beth is in intensive care, the flowers she bought on her final shopping trip — to get black sesame seeds — before the car accident, now wilting. Will she awake?

‘Cold Snap’ was published in The New Yorker, where I discovered Cate Kennedy.

‘Resize’ is a beautiful jewel inside of which a man’s soul is visible in the light that shines from his wife of seven years. As the light moves, the form’s outlines shift and warp.

‘The Testosterone Club’

The preserving kit is in pristine condition—perfectly preserved, you might say, if you were in the mood for making jokes. I valued it highly, when I was married. Yesterday.

But actually, it’s six years. Vivacious humour of a distinctly feminine cast exudes from this story. Another gem.

‘Dark Roots’, the title story, is in the second person. She’s 39, he’s 26. She feels it.

And just as you grab your hairbrush after changing back into your frump clothes, just as you think for a minute you’ll at least brush your hair, you notice in these unforgiving overhead lights those dark roots coming through again already—any fool could see your colour’s not natural. Your hair sits lank and dried-out against your head.

‘Angel’ ends abruptly, the words echoing in silence immediately they enter your mind. They are loud. This collection is loud, insistent, rocking, splendid. Like a sailboat, or a car switching lanes. Inevitable progress and control.

‘Seizure’ charts the faint misgivings that can cloud a relationship. Helen is annoyed by Steve but she doesn’t think she’s being reasonable. She keeps recalling the sight she’d had at lunchtime of a man ministering to another man who’d fallen in an epileptic fit. Things are falling apart.

Helen let the subject rest. She didn’t want them to stay awake. Something was going wrong with their sex life where everything would seem fine between them until the very moment when she felt his questioning hand reach over, and she would remember again a squeamish unwillingness she’d put out of her mind until then. She hated the silence that sprang up between them as his palm would drop heavily onto her hip, the way he always seemed to forget where she liked to be touched. She would feel breathless; not with desire, she recognised with alarm, but with a kind of buried discomfort.

‘The Light of Coincidence’ is about a guy who needs money. There are things, coincidences, that happen to him. He’s got a knack for it. Life is a series of extraordinary events. This little story is tidy and neat, and he’s a real person, a fully-formed character. In seven pages.

‘Soundtrack’ — Rachel is 38, stuck with Jerry and her daughter Emma, who’s in a band called Melting Carpet. Rachel has misgivings, feels life twist in uncomfortable ways around her. She imagines her actions as camera shots. But life continues to surprise her.

‘The Correct Names of Things’ — Ellen works at Eddie Lim’s Chinese restaurant, making $23.50 a day. It is the early 1980s. She studies Russian literature at uni. But she’s still learning about life.

‘No problem,’ he says, and I can tell there won’t be. Back inside, I roll chopsticks inside paper serviettes, thinking that I am twenty years old and the owner of 145 pieces of Confucian advice and I know nothing at all. That night as I’m packing to go, Eddie and Joey sit on the floor in the kitchen shuffling cards, shuffling debts and alimony and war and missing relatives and proceeds from thirteen straight hours’ work in a dead suburban shopping mall. I know nothing.

‘Wheelbarrow Thief’ is a bright jewel of a story. Stella thinks she’s pregnant. Morning sickness? But there’s Daniel’s friends over for dinner. She can’t tell him now. Later. The tension, at the end, between what could have been and the story’s title is delightful.

‘Sea Burial’ is a four-page beauty. Dark roots, indeed.

‘Kill or Cure’ — Helen marries a farmer and must accommodate herself to the new life. Death is an accomplice.

Nothing else breaks the pattern of the day, not even weekends, when things go the same, only slower. When she visits the butcher, who’s always friendly, she notices she has to be careful not to talk too much in what is often the biggest conversation with someone other than her husband for days. In town, she walks slowly down the quiet main street with its two pubs and three takeaways, the big new supermarket dumped at the end looking like a huge shiny toy. She glances into the hopeless little library with its old magazine collection and well-thumbed large-print westerns. She hasn’t gone in there to sign a membership form. Not yet.

Saturday is my day for magazines. A 'magazine', to my mind, is a little storage house of things that become similar simply by their chance proximity. Read are: Quadrant, The New Yorker and Good Weekend (the magazine that comes free with the Saturday edition of The Sydney Morning Herald). The house is, I find, in good order. There is much to enjoy in these offerings.

Saturday is my day for magazines. A 'magazine', to my mind, is a little storage house of things that become similar simply by their chance proximity. Read are: Quadrant, The New Yorker and Good Weekend (the magazine that comes free with the Saturday edition of The Sydney Morning Herald). The house is, I find, in good order. There is much to enjoy in these offerings.Quadrant has just completed it's first 50 years of existence and this issue (November 2006) contains some things that mark that milestone. There is, first off, a three-page 'Tribute' to the magazine by the prime minister, John Howard. Considering Quadrant's circulation is only 1000 copies, this is exceptional. The tribute was delivered by the PM at the magazine's golden jubilee in Sydney on 3 October. He starts with two jokes:

I'm finally succumbing to Peter Garrett's advice, and it's great to embrace an evening of culture and poetry and all of that, after overdosing on my philistine sporting pursuits over the weekend from one side of the country to the other.

Peter Garrett, of course, is the recently-conscripted Labor member (the PM, of course, is Liberal (conservative)) for the Sydney seat of Kingsford-Smith and Shadow Parliamentary Secretary for Reconciliation and the Arts. Formerly, he was the lead singer in the mega-famous rock group Midnight Oil. The other joke is that the PM loves cricket, is a cricket-tragic in fact, and that he reads Quadrant at all is indicative of his seriousness as a person.

Michael O'Connor has written a piece that starts on page 8, 'Australia and the Arc of Instability', about the failed and teetering Pacific Island states on our doorstep, and Australia's manifest obligation to support them. This is topical. Papua New Guinea has just stood down three senior public servants over the events that upset Australian law-makers and bureaucrats: the escape of Julian Moti (the recently-appointed attourney-general of Solomon Islands) from PNG to Solomon Islands aboard a PNG military plane. Moti is wanted by Australian police over child-sex allegations dating from ten years ago. Australia initially suspended diplomatic and ministerial exchanges with PNG following the flight, and Sir Michael Somare, the PNG PM, lashed out at the "arrogance" implied in this action. Now, the new PNG foreign minister has said that they will do everything possible to find out how it happened. The $300 million in aid we send to PNG annually speaks louder than politicians' unregenerate pronouncements.

O'Connor writes:

The reality is that these former colonies are actually or close to becoming failed states. Yet each was left with a viable system of government and enough resources that, properly managed, would provide the basis for steady if unspectacular development. This is what nationalism was supposed to be about and, generally speaking, the metropolitan powers delivered what was needed, often with rare generosity. The failures or impending failures of these former colonies have been all their own work, and after three decades of independence, playing the blame game carries little conviction.

This article is followed by another on the same topic: 'Mendicancy or Membership? The South Pacific and the World Community' by Wolfgang Kasper: