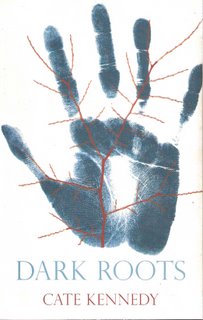

Review: Dark Roots, Cate Kennedy (2006)

Review: Dark Roots, Cate Kennedy (2006)Cate Kennedy writes deftly. Her stories, like Patrick White’s, talk about society, about self-actualisation, and about finding a balance between the personal and the communal, each of which phases of existence has its own demands and imperatives. And there is a great variety of voices in this collection. Each story has its own weight and heft, like a well-made knife. They cut through the reader’s memories and aspirations, and leave a clean mark. They’re terrific. They help you see things more clearly.

On 11 October, Henry Rosenbloom, Kennedy’s publisher at Scribe Publications, a Melbourne-based outfit, blogged about his visit to the Frankfurt Book Fair. During his visit, he sold North American rights for Dark Roots (as well as those for her upcoming novel) to Grove/Atlantic. UK and Commonwealth rights were sold to Atlantic Books. “And suddenly,” he says,

everyone I met seemed to be talking about or wanting to know about ‘the wonderful Australian writer, Cate Kennedy’

It is no myth. She is wonderful. Wonderful and entirely approachable. Her short stories are very short, and they envelop you effortlessly. You slide into them like pulling on comfortable shoes. You are immediately engrossed in their rip and rhythm.

I was engrossed when I read the country story ‘Cold Snap’ in The New Yorker about a boy who catches rabbits and a city blow-in who kills trees. Within a few days I’d driven over to Gleebooks, and found the book on top of the shelf at the left-hand side of the shop, as you enter via the front door. There was a whole stack of them there. I wonder if they’ve gone now.

In September, Stephanie Bishop reviewed Dark Roots in The Sydney Morning Herald and Delia Falconer reviewed it in the Australian Book Review. Kennedy’s also been interviewed by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. She’s an up and coming player, and she deserves it. The questions I’d like to ask her! Such as: whose hand print is on the cover of the collection?

The stories, in brief, are outlined below.

‘Habit’ — a woman is returning to Australia from Columbia. She has cancer. She has bought a lot of cocaine with her superannuation. She has to get through customs. She is nervous. A little thriller of a story. She watches the customs officer unwrap the ceramic statues — three of them — that are covered in newspaper and contain the coke.

‘Flotsam’ — we struggle to work out if it’s a man or a woman, young or old. Time seems to disappear.

Time slides around also in ‘A Pitch Too High for the Human Ear’ as a man’s marriage slowly crumples under the stresses of quotidian life. The dog seems to hold the family together:

Now he takes off down the street and I stop at the end to rest a stitch that feels like a deep knot in my gut pulling upwards, and I jog to the oval and see Kelly trotting slowly to the incline on the far side. I am forty-two years old and the kind of guy who once scored 174 baskets in a season but now gives his wife a StaySharp knife for Christmas, who can barely jog two kilometres, who can never think of what to say, and none of it really hits me until I whistle to watch Kelly bolting back down across the grass and he doesn’t come.

Life is under stress, too, in ‘What Thou and I Did, Till We Loved’, the title taken from a Donne poem. Beth is in intensive care, the flowers she bought on her final shopping trip — to get black sesame seeds — before the car accident, now wilting. Will she awake?

‘Cold Snap’ was published in The New Yorker, where I discovered Cate Kennedy.

‘Resize’ is a beautiful jewel inside of which a man’s soul is visible in the light that shines from his wife of seven years. As the light moves, the form’s outlines shift and warp.

‘The Testosterone Club’

The preserving kit is in pristine condition—perfectly preserved, you might say, if you were in the mood for making jokes. I valued it highly, when I was married. Yesterday.

But actually, it’s six years. Vivacious humour of a distinctly feminine cast exudes from this story. Another gem.

‘Dark Roots’, the title story, is in the second person. She’s 39, he’s 26. She feels it.

And just as you grab your hairbrush after changing back into your frump clothes, just as you think for a minute you’ll at least brush your hair, you notice in these unforgiving overhead lights those dark roots coming through again already—any fool could see your colour’s not natural. Your hair sits lank and dried-out against your head.

‘Angel’ ends abruptly, the words echoing in silence immediately they enter your mind. They are loud. This collection is loud, insistent, rocking, splendid. Like a sailboat, or a car switching lanes. Inevitable progress and control.

‘Seizure’ charts the faint misgivings that can cloud a relationship. Helen is annoyed by Steve but she doesn’t think she’s being reasonable. She keeps recalling the sight she’d had at lunchtime of a man ministering to another man who’d fallen in an epileptic fit. Things are falling apart.

Helen let the subject rest. She didn’t want them to stay awake. Something was going wrong with their sex life where everything would seem fine between them until the very moment when she felt his questioning hand reach over, and she would remember again a squeamish unwillingness she’d put out of her mind until then. She hated the silence that sprang up between them as his palm would drop heavily onto her hip, the way he always seemed to forget where she liked to be touched. She would feel breathless; not with desire, she recognised with alarm, but with a kind of buried discomfort.

‘The Light of Coincidence’ is about a guy who needs money. There are things, coincidences, that happen to him. He’s got a knack for it. Life is a series of extraordinary events. This little story is tidy and neat, and he’s a real person, a fully-formed character. In seven pages.

‘Soundtrack’ — Rachel is 38, stuck with Jerry and her daughter Emma, who’s in a band called Melting Carpet. Rachel has misgivings, feels life twist in uncomfortable ways around her. She imagines her actions as camera shots. But life continues to surprise her.

‘The Correct Names of Things’ — Ellen works at Eddie Lim’s Chinese restaurant, making $23.50 a day. It is the early 1980s. She studies Russian literature at uni. But she’s still learning about life.

‘No problem,’ he says, and I can tell there won’t be. Back inside, I roll chopsticks inside paper serviettes, thinking that I am twenty years old and the owner of 145 pieces of Confucian advice and I know nothing at all. That night as I’m packing to go, Eddie and Joey sit on the floor in the kitchen shuffling cards, shuffling debts and alimony and war and missing relatives and proceeds from thirteen straight hours’ work in a dead suburban shopping mall. I know nothing.

‘Wheelbarrow Thief’ is a bright jewel of a story. Stella thinks she’s pregnant. Morning sickness? But there’s Daniel’s friends over for dinner. She can’t tell him now. Later. The tension, at the end, between what could have been and the story’s title is delightful.

‘Sea Burial’ is a four-page beauty. Dark roots, indeed.

‘Kill or Cure’ — Helen marries a farmer and must accommodate herself to the new life. Death is an accomplice.

Nothing else breaks the pattern of the day, not even weekends, when things go the same, only slower. When she visits the butcher, who’s always friendly, she notices she has to be careful not to talk too much in what is often the biggest conversation with someone other than her husband for days. In town, she walks slowly down the quiet main street with its two pubs and three takeaways, the big new supermarket dumped at the end looking like a huge shiny toy. She glances into the hopeless little library with its old magazine collection and well-thumbed large-print westerns. She hasn’t gone in there to sign a membership form. Not yet.

1 comment:

With Flotsam, it is obvious the story is from the point of view of a woman named Lornie, we share her experiences of pregnancy, douchebag boyfriends and mother-daughter angst.

Post a Comment