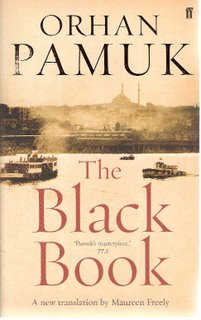

Review; The Black Book, Orhan Pamuk (2006)

Review; The Black Book, Orhan Pamuk (2006)Galip’s wife and cousin Ruya has left him, leaving a nineteen-word note written in green ink. The pen, which he is careful to always leave beside the telephone, is also missing.

He makes up stories to cover for her absence, unable to accept her disappearance as a fait accompli. He is convinced she has run away with someone from her past, possibly her ex-husband. He wanders the streets of Istanbul, Pamuk’s own fateful city, searching for clues.

Interspersed with these detective-like activities are columns written by Galip’s cousin Celal, a journalist. Galip is eager to talk with Celal, who he believes will be able to unravel the puzzle, and help him to find Ruya.

But Celal is also missing and, according to two colleagues Galip meets in his office, in danger of the sack.

The Black Book opens, like Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, in chaos. And as with that other great prose stylist, Toni Morrison, you get the feeling that the writer is telling you less than he knows. The writer holds all the keys. He’s taking his sweet time to tell you the whole story.

Telling stories, or “giving voice to the great mystery” as Pamuk phrases it on page 103 (of a 466-page work), emerges as an ontological imperative that actually gives form to existence. The smallest detail — a damaged, peeling armchair in the dawn-light back streets of the city, a game of hide-and-seek in the dark he used to play with Ruya as a child — everything is equally commensurate with reality. Everything gels in the present moment to form the great ‘now’ of existence.

This is why news, the product of the journalist, and stories, the product of the fiction writer, play such an important part in the novel. As Galip travels through the city, he finds that it is constructing his own story for him. He is being written by the great city on the Bosphorus.

Everyone in the city seems to want to be someone else. This theme is highlighted in a chapter where Galip pays for the services of a prostitute pretending to be a famous Turkish movie actress. In this surreal tableau, Galip plays along, but he can’t really communicate with the actress. And how did Galip talk with his wife, we wonder. He also visits his wife’s ex-husband, an eccentric leftist who was once an activist. In the present moment, this man feels justified by his life of lower-middle-class ease and is happiest, is consciously happy, when he is most like what he seems. Galip, unnerved by his notions, is quick to escape this strange man’s company, emerging at last into the wintry night on the outskirts of the city. This encounter will produce reverberations later on in the story.

A lot happens at night. Scheherazade is invoked frequently in the book. In fact, in one scene, Galip joins a collection of journalists in a bar. They each tell a story, many about love. The succession of stories doesn’t have absolutely to do with the central issue in this book — why did Ruya leave Galip — but the column by Celal that follows seems to point to it. He writes about being yourself. How to be yourself, and not what others want you to be. This seems to be key to solving the riddle of Ruya’s disappearance.

Later, Galip meets a woman who went to school with him and Ruya. Belkis tells him that she had on occasion seen the couple at the Palace Theatre and that she thought that Ruya “could read the secret meanings in faces”. This brief comment chimes with one of the stories told in the bar earlier that day. This, also, will reverberate with later events.

Now we know that Galip is on a quest — to find his wife. Or to find himself. Half-way through the book it is not clear which is the case. Regardless, the strange twists of the plot bring us closer to understanding this city and its inhabitants.

Galip enters into a kind of mania in his attempt to read the secret meanings in faces. Inspired by the new sensations he feels, he continues to pursue his quest, eventually tracking down Celal’s apartment in a building near his own apartment block.

Celal’s columns continue to alternate in the book with the story of Galip’s quest. Now, inside the apartment, Galip reads through all Celal’s past columns and a large collection of other documents, still searching for clues to the location of Ruya. We are suspended in time or, rather, time passes very slowly. And each new day brings a new column by Celal, although no sign has been seen of him for over a week. But Galip will not give up.

His tenacity and the changes in his state of mind that are charted by the narrative establish a dream-like feeling in the tone of the book. This feeling possesses a veracity and calm — a cogent reality — that is in sharp contrast to the complexity of the narrative itself, which is chock-full of interesting events that startle and challenge the reader.

Without wanting to spoil the plot, I can say that there is a mystery that is revealed and it involves a mental state that resembles schizophrenia. Galip is again changed, asserts himself, comes to an understanding with himself and with Celal. But Celal’s world subsequently visits itself on Galip in surprising ways.

Hidden among all the mysteries that Pamuk enumerates is the one that emerges when we pick up a book and read. A defining moment arrives: we are captivated by the weft and weave of the narrative, we feel kinship with the author, we descend the passage to where our brother or sister in spirit is waiting at the door to the other world.

East or West, the door is made of the same material, has a lock and a handle, planks and hinges. Regardless of how forcefully we push it, it opens with identical alacrity. However, the question remains: could this book have been written by a resident of any other city?

At the end of the volume there is a translator's note that states that the original translation by Güneli Gün, brought out in 1994 by Farrar, Straus & Giroux in New York, was "somewhat opaque". This, new translator Maureen Freely says, is due to the agglomerative nature of Turkish (like Japanese).

4 comments:

This seems like an interesting book, but I'm also a bit prejudiced; I've been on a Pamuk fix since reading "Snow" late last year (which was a great book, in my opinion). I also have "My Name is Red" waiting in the wings. I'm looking forward to it, but with Pamuk, I've found that I really need to be in the mood for him, which is why I haven't tackled it yet.

My Name is Red, which was originally published in Turkish in 1998, postdates The Black Book by eight years. Both are wonderful, but so different! I enjoyed the later book enormously as well, and reviewed it on this blog.

I have both The Black Book and My Name is Red, but I haven't started reading them yet.

Thanks for this extremely nicely written review. Have you read Snow? Will be helpful if you do a review on it too. :)

Both are fabulous, Miao. You have a great experience ahead of you. I sincerely hope you enjoy them.

Pamuk is astonishing. He sees things most people never dream of, and writes them down with unassailable aplomb.

His ideas about the East-West divide are incredibly interesting. Reading his books is like taking a crash course in Turkish history.

Post a Comment