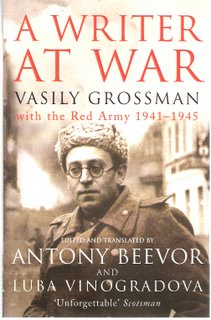

Review: A Writer At War: Vassily Grossman with the Red Army 1941 - 1945, edited and translated by Antony Beevor and Luba Vinogradova (2006)

Review: A Writer At War: Vassily Grossman with the Red Army 1941 - 1945, edited and translated by Antony Beevor and Luba Vinogradova (2006)A dark humour pervades the pages of the many notebooks this writer kept during his years on the front lines of battle in Belorussia, the Ukraine and Russia. Beevor and Vinogradova provide extensive commentary to the, often brief, snatches of prose Grossman wrote in the notebooks between interviewing, writing dispatches and simply trying to stay alive amid the chaos of the front. The expert commentary is knowing and interpretative, fleshing out for the general reader what is frequently assumed knowledge.

Given the strict attitudes of the political cadres, who were constantly working to eliminate sedition, just keeping such notes was fraught with danger. But we are glad that he did. They delineate the human aspects of a war that was, in addition to being very physical, ideological as well. The human aspects of soldiers and civilians who were caught up in the struggle emerge clearly. Anger, frustration, happiness, hubris, fear, valour. Grossman is able to describe individuals in all their imperfection, in just a few lines.

Overweight at 35 and bookish, Vassily Grossman was extremely keen to get to the front when war broke out in late June 1941. David Ortenburg, editor of the Soviet military newspaper Red Star, remembered Grossman’s first book and eagerly accepted him as a reporter, to be located at the front of battle.

‘Vassily Grossman?’ I said. ‘I’ve never met him, but I know Stepan Kolchugin. Please send him to Krasnaya Zvezda.’.

‘Yes, but he has never served in the army. He knows nothing about it. Would he fit in at Krasnaya Zvezda?’

‘That’s all right,’ I said, trying to persuade them [the Main Political Department]. ‘He knows about people's souls.’

As well as trying to stay alive, Grossman took every available opportunity to visit his father, in Moscow. He also worried about his mother, isolated behind enemy lines in western Ukraine. He was right to worry. Jews stood no chance of survival in the face of an advancing Wehrmacht.

Grossman is a survivor who aims to please his editor and, ultimately, the powers that be. Every inch the patriot, his emotions thrill with the soul of Russia, over which he travels in motor vehicles supplied by the newspaper he writes for. Creative leave granted allows him to complete a novel in the company of his wife, before returning to the front at Stalingrad.

Where he continues to scribble in his notebooks, creating pictures of the hellish crossing of the Volga as the Russian troops attempt to stave off the German advance. Water spouts erupt when enemy aircraft fly overhead, ferries are sunk, green helmets bob in the stream.

Snipers attract much attention and praise from Moscow, as they cut down the foreign fighters in droves. Their stories are used for propaganda purposes by the authorities. And possession of an effective sniper brings kudos to a commander, who can then boast of his prowess. The Soviet troops adapt to the changing conditions in other ways, too. They dig trenches twenty feet from those occupied by the Germans, to prevent air attack.

Girls as young as eighteen fly biplanes in bombing raids over German lines. Women forced to collaborate with the Germans are considered traitors and are shot.

But the endless, short descriptions often cause reader fatigue, as the narrative is cut up into tiny segments, fragmented despite the accompanying editorial. You grow tired of being pulled this way and that by this disjointed narrative, and you long for more substantial passages that provide continuity.

We get them when we flick forward to the chapter on Treblinka. Because of Soviet propaganda imperatives, Grossman, although Jewish himself, does not once mention that mainly Jews were exterminated at the camp. He does, however, mention Gypsies. Neither does he note that Ukranians worked at the camp.

Dramatically, using all the literary techniques he can muster, he gives a moment-by-moment account of the processing the victims were subjected to. Writing, as it were, with gritted teeth, he pauses in his narrative to contemplate the historical moment, before succumbing once more to a spasm of patriotic fervour.

It is infinitely hard even to read this. The reader must believe me, it is as hard to write it. Someone might ask: ‘Why write about this, why remember all that?’ It is the writer’s duty to tell this terrible truth, and it is the civilian duty of the reader to learn it. Everyone who would turn away, who would shut his eyes and walk past would insult the memory of the dead. Everyone who does not know the truth about this would never be able to understand with what sort of enemy, with what sort of monster, our Red Army started on its own mortal combat.

We must remind ourselves, again, that Grossman is writing for an Army organ. They pay his way, they provide him with the passport he needs to access these locations. But we find it hard to countenance the fact that this Jewish intellectual would not, at least in some way, make note of the fact that it was, overwhelmingly, Jews who died in the camp.

Eventually, his compliance in this and other matters would count for little. His novel Life and Fate, modelled after Tolstoy’s exceedingly long doorstopper of a century earlier, would be banned by the authorities because of the way it drew parallels between Communism and Nazism.

The cultural police seized not only all the manuscripts they could find but also the carbon paper and typewriter ribbons. Fortunately, Grossman had given a manuscript to “a friend” and the novel was eventually smuggled out of Russia to Switzerland, where it was finally published.

But the last years of Grossman’s life were blighted by official obloquy and his earlier works were withdrawn from circulation. (“In the eyes of the Soviet authorities, Vasily Grossman was virtually a non-person in political terms.”) He died of stomach cancer in 1964. Life and Fate was finally published, in 1981, twenty years after the KGB confiscated the manuscripts.

The book under review materialised due to Beevor’s work, in Russian archives opened up following the collapse of Communism, on his book Stalingrad. In the acknowledgements here, Beevor points to the cooperation of the Russian State Archive for Literature and the Arts.

No comments:

Post a Comment