Review: A Tale of Love and Darkness, Amos Oz (2005)

Review: A Tale of Love and Darkness, Amos Oz (2005)A "sickly child", a "word-child", Oz was born Amos Klausner (he changed his name to Oz, which means 'strength' in Hebrew, when he went to kibbutz Hulda at the age of 15), the son of parents who had arrived in the Levant during the time of British dominion in the late nineteen-thirties who were escaping rising anti-Semitism in the Europe they had grown up in.

Both my parents had come to Jerusalem straight from the nineteenth century. My father had grown up on a concentrated diet of operatic, nationalistic, battle-thirsty romanticism (the Springtime of Nations, Sturm und Drang), whose marzipan peaks were sprinkled, like a splash of champagne, with the virile frenzy of Nietzsche. My mother, on the other hand, lived by the other romantic canon, the introspective, melancholy menu of loneliness in a minor key, soaked in the suffering of broken-hearted, soulful outcasts, infused with vague autumnal scents of fin de siecle decadence.

The narrative arc of this memoir forms its axis around his mother's suicide. We know of it from the beginning but not until the last few pages of the book are we told how it happened. The narrative moves dramatically back and forth in time, building slowly throughout this 270,000-word monolith of a work.

Oz remembers events in great detail, from the time he was a small boy. The gradual accretion of detail serves to create strong characters who appear again and again in the narrative. Such as the little bird that always sings the first few bars of Fur Elise outside their tiny apartment in Jerusalem. His maternal and paternal grandparents come alive, as do his teachers, his parents' other relatives (aunts and uncles), and people from the neighbourhood in this lower-middle-class district of the city. As for his own friends, they are not detailed to any depth.

I have never again blended happily into an ecstatic crowd, or been a blind molecule in a gigantic superhuman body.

This after, as a young boy, he had exploded in laughter at the words of Menachem Begin during the time of the Jewish settlement, and been chastised by his great uncle. This passage immediately precedes the author's manifesto of intent: to escape his parents, the stultifying "suffocation of life in the basement" and all that it contained. He was only 12 years old, but already his mother had "turned her back" on him and his father's failure was a "burden". This is a turning point for the young Amos. The narrative immediately moves to the kibbutz, where he tried hard to fit into a new lifestyle of work and independence. He lived there from 1954 to 1985.

The novelty of kibbutz life was apparently something of a joke for some people living in Jerusalem. Kibbutzim were considered somewhat 'socialistic' and therefore suspect. For eastern European Jews who had escaped both Hitler and Stalin, the idea of living on the land was something less than edifying: hard physical labour and nothing else. At least that is how Oz' father treated the idea. He had to be brought around gradually to accepting his son's decision. But he had remarried by that time and Amos — who never once talks about his stepmother — felt constrained by his father's aspirations. They had certainly never got him very far, Amos must have thought. His father aspired to be an academic, was very cultured, but was always refused and eventually worked as a librarian throughout his life in Jerusalem.

After moving to the kibbutz, Oz discovered a work of Sherwood Anderson: Winesburg, Ohio:

At half past three in the morning I put on my work clothes and boots, ran to the tractor shed from which we set out for a field called Mansura to weed the cotton, snatched a hoe from the pile, and till noon I charged along the rows of cotton plants, racing ahead of the others as though I had sprouted wings, dizzy with happiness, running and hoeing and bellowing, running and hoeing and lecturing myself and the hills and the breeze, hoeing and making vows, running, excited and tearful.

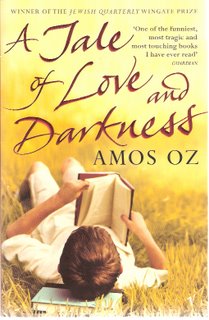

A Tale of Love and Darkness, with its red-and-yellow, slightly Asiatic cover and lacquer-red spine, is in part an autobiography, a description of how he became a writer. From the time as a little boy when he wanted to grow up to be a book, to his mother's decline, to his decision to go to the kibbutz, to his discovery of Sherwood Anderson's novel, we are treated to a delightful lecture on the genesis of genius. Oz is 67 years old this year. This is a tribute to the past, a slow hymn for the state of Israel, a solemn and joyful farewell to the past, a gesture of sorts to the future. A wonderful book.

No comments:

Post a Comment