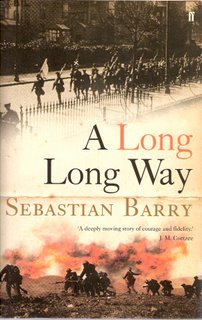

Review: A Long Long Way, Sebastian Barry (2005)

Review: A Long Long Way, Sebastian Barry (2005)Willie Dunne's father is a policeman in Dublin when Willie goes off to war in Flanders. Against a background of horrific warfare the Irish independence push flares up. Conscripted in 1917 at age eighteen, Willie does three years without accident in the trenches. The moral problems he and others face are brought to the fore by a series of plot devices that are intricately woven into the narrative.

The beautiful, poetic language employed throughout this wonderful book is counterpoised by the vivid dialog, that brings to life life in the trenches. Country as well as God are the catchcries of the soldiers and their tribulations are mesmerically produced in a distinct language invented for that specific purpose.

The journey seems endless as the war drags on and more and more of the 16th are killed or incapacitated. Willie seems blessed. We wait for the end that we know must come. We wait and wait, but still it does not come. Barry deftly balances the troubles at home against the historical record of the Great War to produce great tension and suspense in the reader. But he also brings to bear the methods of modernism on a time when writers used different tropes. This is effective and stirring, as when Willie thinks on the process of thought:

Funny how a person thought of one thing and then thought of another thing. And then another thing. And was the third thing brother at all to the first? He stopped a moment and leaned on his spade like a bad worker.

And again, as he thinks about language:

Willie had no words to tell what he was feeling in response to Father Buckley's words. He wondered suddenly and definitely for the first time in his life what words might be. Sounds and sense certainly, but something else also, a kind of natural music that explained a man's heart or heartlessness, words as tempered as steel, as soft as air.

Willie's journey becomes in time a parable for the Irish state as it gradually stirs into motion, against the centuries-old dominion of England. And it is also simultaneously a parable of the commitment of all the soldiers, from whatever country, who died in the Great War. May they never be forgotten.

No comments:

Post a Comment