Review: Live and Learn, Joan Didion (2005)

Review: Live and Learn, Joan Didion (2005)It's very difficult to extract quotations from the pieces in this collection, which spans from 1966 to 1990, comprising a large part of the journalism of this diminutive author. The four-and-a-half-page piece titled Bureaucrats is just one of the more concise exemplars of a very concise and elegant style.

The flow is rapid, which is why quoting bits is so hard, because you never really know when you should stop quoting, to get a nice, homogeneous section complete in itself. The flow doesn't stop at the end of the paragraph, even at the end of a section; it seems to continue on meandering like a broad river on a flat plain, certain that eventually it will come to the sea.

In Bureaucrats, Didion does short work on the self-obsessed functionaries in the traffic control office — it's not clear though if that's what they do, although you'd expect something more than just 'verifying incidents' in their remit — and we only wish she would do a similar job on some of the colossal failures in our own back yard, the Cross-City Tunnel for example.

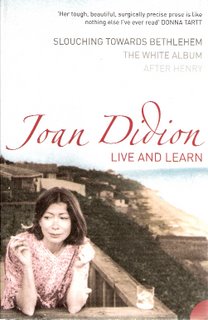

There is no introduction to this book, although the back cover tells us briefly what it contains. But there is no synopsis of Didion's life, nothing about where she was living when these pieces were written, what prizes she won (if any) and what events might have had a bearing on her journalism. Of course she is still writing — she has a piece in the latest New York Review of Books on Dick Cheney — and so presumably considers herself to be outside the club of writers whose anthologies get this sort of treatment. She was born in 1934. The picture on the cover of this 'omnibus edition' shows a woman considerably younger than she must now appear, presumably to show us what she looked like at the time these essays were written, or at least some time at the mid point of that expanse of years.

We do not get, for example, any indication of the reason for entitling the second section of this 'omnibus edition' The White Album. We do get an intro for Slouching Towards Bethlehem: the title comes from the inanely famous Yeats poem of 1920, 'The Second Coming', which retired politico Barry Jones has also used for his new book, just out.

California obviously unsettles Didion:

'What a sacrifice on the altar of nationalism,' I heard an actor say about the death in a plane crash of the president of the Philippines. It is a way of talking that tends to preclude further discussion, which may well be its intention: the public life of liberal Hollywood comprises a kind of dictatorship of good intentions, a social contract in which actual and irreconcilable disagreement is as taboo as failure or bad teeth, a climate devoid of irony. 'Those men are our unsung heroes,' a quite charming and intelligent woman once said to me at a party in Beverly Hills. She was talking about the California State Legislature.

Hers is an existential angst of a particularly worldly kind, and one that throws up glistening jewels of prose ('Old Man River' is humming along in my head as I read).

But what is most striking about her essays is that they don't 'date'. As fresh as when they were first written — presumably on a typewriter of some kind — thirty and forty years ago. So: this is the face she presents to the world, rather than the concession to her publishers that adorns the book's cover: an ageless, firm and silvery-liquid aspect with the purity of wind chimes early on a spring morning.

My only quibble with this 'omnibus edition' is that rather than 'live and learn' it should have been titled 'read and think'. A splendid collection, anthology, whatever-ya-call-it. Recommended.

No comments:

Post a Comment