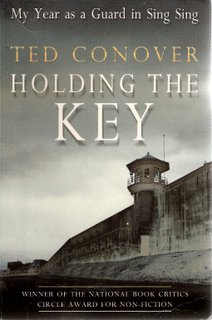

Review: Holding the Key: My Year as a Guard in Sing Sing, Ted Conover (2000)

Review: Holding the Key: My Year as a Guard in Sing Sing, Ted Conover (2000)As well as spending seven weeks in the training Academy, and the remainder of a year in the service of the New York Department of Correctional Services, Conover read at least 37 books in the writing of this interesting work of literary journalism. Sing Sing, one of the 71 prisons in the state, is located nowadays in a prosperous residential area of Westchester County. But back in 1825 when it was first planned, the site was a remote quarry that would furnish building materials for the growing metropolis.

The complex procedures used in the maximum-security prison by prison guards — the correct term is correctional officer (CO) — and the air of paranoia that motivates them to act in the way they do, are published for our scrutiny, amusement, savour and judgement. At the time of publishing, DOCS was the second-largest employer in the state. When the book came out, DOCS at first barred inmates from reading it. Then they changed their minds and resorted to excising certain passages from copies distributed in prisons: "Mainly Academy stuff ... along with what to do during a red dot emergency and the ways in which officers were made vulnerable by the antiquated configurations of Sing Sing's exercise yards." Although at first DOCS was dismissive ("'Why would I be interested in the view of a newjack?'" a DOCS spokesperson told a newspaper reporter following the release) Sing Sing COs came to the talk and book-signing organised by the publishers in Ossining, the suburb where the prison is situated.

Conover initially became interested in the book idea after talking to some union representatives. When he approached DOCS with the idea of following a new recruit through training and into the prison "DOCS turned me down flat", writes Conover. After writing up the application form in 1994, he waited several months before receiving notice of his successful application.

A 'newjack' is a newly-graduated OC. On the floors of the prison, they are subject to particular attention by the inmates. They are considered fair game in the endless battle of wills between OCs and inmates.

Sing Sing was a world of adrenaline and aggression to us new officers. It was an experience of living with fear—fear of inmates, as individuals and as a mob, and fear of our own capacity to fuck up. We were sandwiched between two groups: Make a mistake around the white-shirts and you would get in trouble; make a mistake around the inmates and you might get hurt.

Conover gradually decides that some methods of coping with this dichotomy are better than others. One new officer, who he names Smith to protect his identity, gets his attention because of the way in which he goes about his work:

... it seemed to me that Smith succeeded because he viewed the inmates as human beings and was able to maintain a sense of humor in the face of the stress of prison life—traits that are two sides of the same coin.

Conover is glad to leave the prison for the last time after his allotted year expires, to return to his privileged life of a writer, to his customary pursuits, to get away from the fear and anxiety that has infected his dreams and caused his personality to change.

This is a very satisfying read.

9 comments:

Hi Dean, thanks for the review. I think the US prison system is fascinating - I'm especially interested in how it is an industry that of course needs to perpetuate itself and is therefore absolutely not interested in reform. Eric Schlosser, the author of Fast Food Nation, is currently working on a book about it - that's one to look forward to.

Thanks for the tip. I read about his upcoming prison book in The New New Journalism, but it slipped my mind.

I find it difficult to think of Sing Sing now without an image in my head of the fictional 'Sing Sing' in the film The Producers, complete with a dancing, laughing chorus line of prisoners. It's heralded by a classic musical-type refrain, 'Going to Sing Sing - Going to Sing Sing', the first time on the notes D - B - A, the second time on the notes G - E - D (or similar, I haven't got perfect pitch!)

Do you look like Bunyip Bluegum in real life?

I look more like Norman Lindsay, actually. But I'm not as good a painter, so I stole his image instead of drawing one for myself.

On my first admittance to Pentridge I had a photo of the place which I'd torn from Post magazine. The screws (Prison Guards, Correctional Officers) all had a good laugh about it, then took it off me.

Sorry to hear that. Did you spend a lot of time there? If you read Conover's book some time, I'd be really interested in hearing what you thought of it. I personally really enjoyed reading it. But of course, it's from the point of view of a CO, not an inmate.

It was a bum rap: vagrancy, I did three weeks and sang in my cell every night. We were locked in from 4pm until 7am, and had to salute the fat governor every morning as we filed out to the yards. One day I forgot, and was ordered to scrub old paint from the floor of a cell where they stored the stuff - an impossible task of course, and quite a joke. That was in the remand section, but when I was transferred over to the jail proper (to the YOGS: young offenders group) I found they had some cunning plans. We had to do PT out on the oval every morning: gymnastics and piggy back fights. The reason was loudly explained to us by one of the Correctional Persons. "Der food in here ist not gut! So you vill need exercise to keep healthy." That's what he said. But then he put on an enormous grin. "But wid dese exercisings, you vill get so fit you vill be able to outrun ze cops!"

It was like the army, we were lined up for inspection, barked at all the time, and marched to each meal, and to our cells, accompanied by military music. The food was dreadful, one meal I'll never forget is the Pentridge Classic: a bowl of stew with two scoops of rice in the centre. It was a horror. The bread rolls were always stale except on Fridays, which is probably the day they baked the things. Every morning in the yard before breakfast we were presented with a ration of powdered milk and sugar, one of each, wrapped cone-shaped in paper: pages from old electoral rolls. And instead of mixing it in my mug with water, I used to eat the powdered milk straight away, which meant I had nothing to put on the porridge. But I dumped my entire day's ration of sugar on it anyway, and ate it scalding. Food was the most important thing. I was always hungry, dreaming of cream cakes, boston buns and so on. Then to celebrate my last night there they put me in C Division; the most antiquated part of Pentridge. This was their scare-chamber, their haunted house, the hope being I guess, that the experience might end my life of crime. The cell was tiny, with no light, no bed, and no dunny. I was given a bucket to shit in and a stub of candle, that's all. In the morning we all trooped down rickety stairs to empty our buckets into a sort of pond in the centre of the yard.

I was released from the place wearing a pair of their woollen socks, and with absolutely no desire to ever go back of course. But then I was only a boy; seventeen years old, and still learning. What I learned really was about three monkeys on a bench: a magistrate and two JP's; pillars of the community. They locked me up and locked me out. Then went home for their dinner, the dirty dogs, and forgot all about it. Well I've served two other terms, but only a few weeks in total, so for what I've done I'm well ahead; miles ahead, just can't be overtaken.

It's been war, but I didn't start it. I declared war on no one. It was their idea completely.

Sounds like a lot of fun.

You should write it down and get it published in some magazine. Not often you get a crim's-eye-view of the prison system. I think most people are fascinated by the whole thing, especially because of the unique culture that develops inside, the arcane punishments that are devised, the 'privileges' and lack of them, the violence and risk of assault. Most people are sick of the fear in their everyday lives, so a bit of a look at how the other half lives does us good. It's like the celebrity tabloids, as well: something different to alleviate the misery of earning just enough to pay the mortgage and buy a Thai take-away once a week.

One of the guards was a fierce looking bloke, the sort who'd send you over the top in a bayonet charge, and shoot you if you hesitated. Everyone was in awe of him. I heard that two ex-prisoners stole his car and mailed it back to him, bit by bit. He got dashboard knobs one week, then a headlight, steering wheel and so on. I'd say there was some truth in it, but jail tales are always hotted up. It's a competition.

Post a Comment