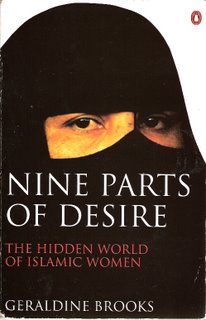

Review: Nine Parts of Desire: The Hidden World of Islamic Women, Geraldine Brooks (1995)

Review: Nine Parts of Desire: The Hidden World of Islamic Women, Geraldine Brooks (1995)Winning the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction on 17 April must sometimes feel odd for Brooks when this, her earlier, journalistic, effort, received no such plaudit. It's a shame. But the world in 1995, apparently (we are often told nowadays), was a different place. Eleven years separate us from that moment in history, but for many of the women whose lives Brooks chronicles things are not much altered. And fundamentalism is not so recent, we learn.

Working from a liberal humanist point of view, Brooks' writing makes it easy for Westerners to understand the significance of the strictures that Islam enforces on half its population. But one considerable problem facing Western readers is the unfamiliarity of names. They are so strange that it is difficult to care. This is a fundamental and urgent shortcoming that I think can only be addressed by Westerners reading more such books. The more often we are confronted with these strange names, the less alien they will seem. It is a slim hope, however.

Brooks makes her case strongly and makes it often. Which is not that hard, really, when she is constantly confronted by situations that would be totally unacceptable for a Western man or woman, were the roles reversed. As she said in an interview with Enough Rope's Andrew Denton on 18 April 2005:

[T]he dirty little secret of foreign correspondents is that 90 per cent of it is showing up. If you can find a way to get there, the story, the reporting, it's the easiest you'll ever do. 'Cause the drama's everywhere. You don't have to have a fat contact book, and you don't have to be well connected at the Elysee Palace and all that stuff. You just have to get there and show up, and be able to put up with a bit of discomfort.

Working as a foreign correspondent for six years brought her into contact with many, many women (and men) and with many situations where women were subject to intolerable restraint.

Sometimes, however, their choice to wear the chador or hijab was voluntary. This is sad. To adopt this form of dress just because "it is ours" and doesn't emanate from the corrupt West seems as idiotic as applauding the assassination of the Japanese translator of Salman Rushdie's Satanic Verses because only such events make the headlines. Stubborn, willful denial of right makes it all seem so pointless. Pride in Islam seems to be a very insignificant thing when faced with the realities of genital mutilation, honour killings, child marriage, unemployment and the lack of eduction for girls. And that's only a partial list.

In Muslim societies men's bodies just weren't seen as posing the same kind of threat to social stability as women's. Getting to the truth about hijab was a bit like wearing it: a matter of layers to be stripped away, a piece at a time. In the end, under all the concealing devices—the chador, jalabiya or abaya, the magneh, roosarie or shayla—was the body. And under all the talk about hijab freeing women from commercial or sexual exploitation, all the discussion of hijab's potency as a political and revolutionary symbol of selfhood, was the body: the dangerous female body that somehow, in Muslim society, had been made to carry the heavy burden of male honor.

Despite differences between the many, many Muslim countries (some are more 'liberal' than others, some offer more opportunities to women) this paragraph goes to the core of Brooks' story. And it is reported, remember, not fictionalised (although she writes using some literary techniques that bring the drama closer to home). She is just telling us what happened. The aggregate effect is mind-numbing.

Brooks has read the originary texts. She tries to find some redemptive elements in the Koran and the haditha. She works hard not only to understand but to empathise. But extreme forms of Islam stymie her understanding and deaden her responses.

Saudi Arabia is the extreme. Why dwell on the extreme, when it would be just as easy to write about a Muslim country such as Turkey, led by a woman, where one in six judges is a woman, and one in every thirty private companies has a woman manager?

I think it important to look in detail at Saudi Arabia's grim reality because this is the kind of sterile, segregated world that Hamas in Israel, most mujahedin factions in Afghanistan, many radicals in Egypt and the Islamic Salvation Front in Algeria are calling for, right now, for their countries and for the entire Islamic world. None of these groups is saying, "Let's recreate Turkey, and separate church and state." Instead, what they want is Saudi-style, theocratically enforced repression of women, cloaked in vapid cliches about a woman's place being the paradise of her home.

What would be great is if Brooks, or someone (a journalist) like her, would be to revisit the same scenes, now, in 2006, to show just how little (as I suspect) has changed.

4 comments:

Dean,

You wrote:

"Sometimes, however, their choice to wear the chador or hijab was voluntary. This is sad."

And then, still keeping to the same topic and within the same paragraph, you wrote:

"Stubborn, willful denial of right makes it all seem so pointless."

Aren't the two sentences contradictory? Haven't the women made a willful and deliberate decision to exercise their right to wear whatever they choose? Shouldn't the observer then respect that decision?

Unless, you're saying that Muslim women (in Middle Eastern countries) are sheep who can't think for themselves and don't know any better?

In case you haven't already, I recommend you read "In Search of Islamic Feminism: One Woman's Global Journey", by Elizabeth Warnock Fernea. Written by a professor in Middle Eastern studies, it comes from a far more reliable authority on Muslim behaviours and attitudes in the Middle East than a journalist in search of a sensational story.

Cheers.

- Ruhayat X

I think Brooks is not "a journalist in search of a sensational story".

Six years spent in Muslim countries would have removed the need for sensationalism, I think.

But I thank you for your suggestion. Unfortunately, I am studying this year, and extra-curricular reading isn't currently possible.

I suggest you read Brooks' book. You might also like to read what Muslim women have written, such as Ayaan Hirsi Ali and Hamida Ghafour. Both are mentioned on this blog.

Dean,

yes, I've read Brooks' book, 4 years ago, and remember finding several inaccuracies in it, mostly mistranslations of Quranic verses. And, like Ayaan Hirsi Ali, she frequently makes the mistake of confusing "cultural traditions" for "Islam".

The title of her book supposedly comes from the fourth caliph, Ali, but she does not provide its source. This saying is unknown to us; there is a similar saying attributed to the prophet which used to be popular, but has consequently been proven to be falsified.

Her revelation in the book that she has embraced the politics of her husband's faith (he's Jewish; she converted to Judaism) doesn't help, either, especially with the prevalent snarky tones.

On the other hand, I appreciate the even-handedness and knowledge exhibited by Prof Fernea and Karen Armstrong. Their observations are not always kind to Muslims, but since Islam as interpreted by Muslims are not perfect, I can accept their learned criticisms.

You don't have to post this up, it's a bit lengthy. Best of luck for your studies.

Cheers.

- Ruhayat X

Books on Islam and especially books regarding the treatment of women in the Islamic world tend to be, for the most part, biased and one-sided, clinging to cries of human rights violations and oppression. And while it's true that these things do occur in some countries, that is by all means a cultural practice and is due to the misinterpretation of the religion by fundamentalist regimes. Islam in its truest form is a religion that honors and respects the woman, and many women choose to wear the veil as a sign of modesty and submission to God. I thought Brooks did a pretty good job showing the cultural implications and contrasting them with Islamic law, especially with issues like female circumcision and abuse, which are clearly not permitted in Islam. Although I sometimes detected a hint of negativity in her voice, I believe this to be one of the more accuate books on this subject that can be found today.

Post a Comment