Like Dickens, Frith was a special correspondent for posterity, and by freeze-framing everyday folk in their "unpicturesque" mid-century clothing, doing humdrum things, his work has, as he'd hoped, had a "chance at immortality". It is difficult for us to appreciate how revolutionary this was for an art world that saw historical and literary scenes as the only proper subject matter for high art.

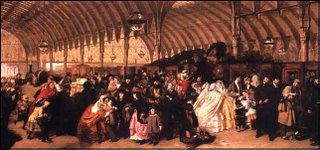

Frith's revolution happened almost by accident: sketching on holiday at Ramsgate in 1851, he sensed that groups of people were "unconsciously forming themselves into very paintable compositions", and he was struck by the variety of the human animal. Frith's paintings form a compendium of brilliantly realised human features and expressions, and the viewer's eye works tirelessly to follow the gazes passing from upwards of 80 characters in each panorama. Who is looking at whom, why, and what are they thinking?

Frith seems to occupy a place of distinction in the Romantic tradition. It was Wordsworth, of course, who first made notorious the rendering of common life in British literature. There were precedents, however, notably the scene-portraits written by William Cowper (widely considered to be a seminal influence on the younger poet).

Painting in Britain seems to have needed time to catch up with the steps already taken in the prosodic sphere. Cowper was writing in the 1760s about common folk in the countryside where he lived in seclusion with his rabbits and his translations of Homer. Then came the thunderbolt of Lyrical Ballads in the early 1790s. But these early renderings of common life were enthusiastically lambasted by reviewers.

In our ruthlessly secular age, there is little danger of this type of thing reoccuring, and unsurprisingly Wise exalts this aspect of Frith's work.

... Frith had tired of churning out endless Merry Wives of Windsors and highwaymen, and felt a strong urge to depict "modern life – with a vengeance", just as novelists had been doing for more than three decades.

No comments:

Post a Comment