This post is the twenty-third in a series and the second to chronicle diets. In November I moved to live temporarily in a furnished apartment near Broadway Shopping Centre near the centre of Sydney.

2 November

This morning I physically came in at 7.2kg below the initial weight (mentioned in last month’s “shopping list”). The new reading was 113.3kg (a single figure minus half a kilo for clothes): still some distance from target weight, but a distinct improvement.

I made the reading with a Withings scale purchased on Amazon on 20 October. It cost about US$90, which came to about A$126 – postage was free as I’m a Prime subscriber. It arrived at my place on the day of settlement for my apartment, so I organised to meet, at the property I occupied for five years (ownership of which had now been transferred to a third party), the real estate agent, Tom, who let me into the lobby where the package was sitting waiting to be picked up. Standing there, we chatted for five or ten minutes.

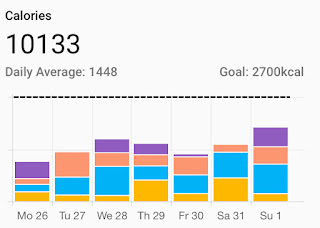

I used the scale immediately but, due to the fact that I was between lodgings, I didn’t use the scale consistently, and at the same time each day, until this week. Displaying my activity levels and calorie intake for the week that had just ended are charts shown below. The first shows calories eaten per day (as mentioned last month, the colours represent different meals and snacks: yellow is breakfast, blue is lunch, pink is dinner, and purple is snacks).

The second chart shows activity for the same week ending 1 November (with Thursday being moving day):

The third chart shows the categories of nutrients (or macronutrients) eaten:

With 568g of carbohydrates consumed during this week, at an average of 81g per day, I was still eating too many starchy foods, so vowed to continue my quest.

On this day I also received another email from Noom, informing me of a decision they’d made to waive the subscription fee they’d asked me to pay when I’d first entered information into the promotional web page.

Now, I wasn’t tempted. This California-based company had gotten an ad inserted in my Facebook feed, which I can access on my mobile phone. To start, you have to enter a good deal of personal data. At the end of the process they ask for money so that you can subscribe.

I reckoned at the time that since they’d just stripped me of a lot of useful data that they should let me use their service gratis, so I just went away from the site. A bit later the same day they sent me an email – in the name of a staffer – letting me know they’d decided to waive their fee and would I like to use Noom (which advertises itself as allowing you to lose weight without a restrictive diet). The new email didn’t say it but implied that there would be grace period absent a fee, then the usual fee would apply.

Both times I ignored their messages. They had had a chance to engage me on my first meeting with them. Now, I unsubscribed myself from their mailing list.

Another thing I found curious was a feature I now noticed in my iPhone’s Health app. This is labelled “active energy” but I didn’t recall ever having seen it before. The term, deriving from the Apple Watch (I don’t have one), has to do with movement tracking, and presumably kicks in when you carry your phone around in your pocket while doing errands or exercise.

Why did this information suddenly appear on my phone?

Whenever I use the Withings scale I’m also putting weight readings into the Apple Health app. The first “active energy” entry is tagged with the date of the day on which I picked the scales up at my apartment building. This, in addition to the data I’m constantly entering data into the phone with the FatSecret app whenever I eat something, is no doubt the reason I saw this reading.

3 November

With the move to my temporary lodgings complete I went shopping and bought a few things (see receipt below): half a roast chicken, milk, tomatoes, mushrooms, avocadoes, baby spinach, an oak lettuce, strawberries, eggs, smoked cheddar cheese, olives, laundry liquid, and flavoured sugarless mineral water.

Later went back to Coles and did more shopping, buying (see receipts below) canola oil, Bega cheese, salad dressing, salmon fillets, low-carb snacks, low-carb bread, toilet paper, tissues, apples, pot scourers, and dishwashing liquid.

4 November

Weighed myself and came in at 112.1kg – this time in the morning before breakfast, with clothes off. Today’s was the first naked weigh-in. All my figures to this point in time mightn’t have been entirely accurate and, in addition, weigh-ins at the doctor’s office were performed using a different set of scales.

Later, went to the shopping centre and at Coles bought sandwich bags, ground coffee, and sugarless flavoured mineral water. Also bought tea towels at a different shop in the same building.

5 November

Down 300g today at the morning weigh-in. Later went out to run errands and popped in at Coles to buy sugarless flavoured mineral water.

6 November

Up 200g today at the morning weigh-in. In the evening went to Coles and bought cheese, salmon fillets, barramundi fillets, tomatoes, apples, kimchi, flavoured sugarless mineral water, a pair of tongs, and a frying pan with a lid (because the frying pan in the apartment was misshapen and the lid was too small). When I got back to my building, I found that someone’d kicked the street door so severely it wouldn’t close.

7 November

The door was fixed by lunchtime today, when I had the thought – impelled by a comment my GP made a month prior – that Coca Cola had imperiled the health of millions of people. Our need for a hit can hardly fail to be understood as a reason – perhaps, to be fair, one among many – why people commonly seek highs using various alternatives to sugar, such as alcohol and drugs.

On this day went to an event at the gallery next-door to the new house, with a friend who has a dog named Sugar… This day’s morning weigh-in gave a figure of 111.5kg.

8 November

Morning weigh-in gave a figure 500g lower than the day before. Later went to Coles and bought apples and sugarless flavoured mineral water. Here’s calorie intake for the week:

Then activity (steps):

Finally, macronutrients:

With 427g of carbs eaten during the week, I’d gone below the levels set the week before: about 60g of carbs per day which is, evidently, enough to get you through the day – energy-wise – but also an amount small enough to allow you to lose weight.

11 November

Went to Coles and bought (see receipt below) sliced ham, pastrami, strawberries, a pear, apples, baby spinach, taramosalata, hummus with jalapeno, flavoured sugarless mineral water, and low-carb snacks.

12 November

Had some errands to do and while out popped in at Coles to buy (see receipt below) sugarless flavoured mineral water.

13 November

Went to Coles and bought (see receipt below) smoked cheddar cheese, an avocado, apples, strawberries, milk, low-carb snacks, and sugarless flavoured mineral water.

14 November

After my weight went up a bit due to a couple of days spent with friends, today it was down again, this time to 110.7kg. See below for a month’s-worth of measurements, charted on a graph.

I’m not sure what that spike in the middle was caused by – I’ve no recollection of an event that might’ve made it. I worked out how important it is to weigh yourself at the same time each day, as consumption of even a small amount of food makes your weight increase. You’ll always weigh more at bedtime than you do in the early morning before having coffee.

I also found that reversals should be dealt with soberly, the best policy being to take it a day at a time and not to be disheartened by small setbacks. Sticking to the diet isn’t hard with the app as you can get feedback even when planning meals, allowing you to eliminate certain foods and replace them with others that will be nutritious without the danger of bringing unwanted elements into your system. But cutting back on carbs doesn’t mean that you have to go without other types of food that you enjoy. I can still eat cheese (which I love) and add full-cream milk to my morning coffees. I can also eat delicious hummus and add a splash of dressing to a fresh tomato. As shown in the receipts posted above, I found two different brands of low-carb snacks that are filling and tasty.

On the other hand, most prepared food that you’ll find walking on the street – passing, as you do, dozens of shopfronts with display windows featuring treats (and food cabinets in restaurants also show plenty for sale) – is mostly useless. The occasional healthy option might appear on menus but if you want to lose weight in the way I have been describing you’ll prefer to eat, at home, what you buy from select aisles in the supermarket. Not all supermarkets offer the things I include in my list.

16 November

This morning’s weigh-in gave a reading of 109.6kg. Here is the calorie chart for the week just ended:

And … the activity chart for the same:

Finally, the macronutrient chart for the same span of time:

Carbohydrate intake for this week was an average of about 62g per day.

On this day drove to Camperdown and bought two kilos of ground coffee at Campos, then went in the car to Broadway Shopping Centre and at Coles bought (see receipt below) tuna steaks, a ling fillet, baby spinach, apples, cheddar cheese, low-carb bread, sugarless flavoured mineral water, hand soap, and body soap.

18 November

Up almost a kilo on the previous reading, on this day I went to Coles and bought (see receipt below) low-carb snacks, blueberries, and sugarless flavoured mineral water.

19 November

Morning weigh-in had me down to 109.5kg and on this day had errands to do in Pyrmont so popped in at Woolworths and bought (see receipt below) taramosalata, hummus, brazil nuts, avocados, mushrooms, smoked cheddar cheese, and marinaded goat’s cheese.

21 November

It seemed on this morning that the big gains of the early days had come to an end, and that from now on it would be small increments of progress toward my goal. I felt like this because the morning weigh-in had me a bit heavier the two days’ prior.

Essentially, my weight had been steady for a week. I tried to shrug off disappointment and later went to Coles to buy (see receipt below) low-carb bread, low-carb snacks, blueberries, and sugarless flavoured mineral water.

23 November

This morning’s weigh-in gave a reading of 109.1kg. The week’s calories were, as follows:

Activity for the week was, as follows:

And (lastly), macronutrient values for each day of the week were, as follows:

Consumed 381 grams of carbs for the week (in total), averaging about 54g of carbs per day, which is well within the allowed band.

In the morning I drove to Pyrmont to see the GP, then popped in at Woolworths to buy (see receipt below) lamb chops, porterhouse steak, pork chops, salmon fillets, a Nile perch fillet, eggs, walnuts, seafood salad, red Leicester cheese, milk, apples, and sugarless flavoured mineral water.

Chatting with the GP once more useful. Dr Nanda advised me that weight loss in many cases can initially be rapid, and that the decline tends to be slower after a period of time has elapsed when excess water is lost. He said that I should be happy if I lose only nine or 10 kilos over the next six months. I said that my policy with regards to the speed of weight loss is patience. I have to be happy, I said – wild and optimistic, at the end of the month it seemed likely to remain – with losing only about half a kilo each week and reckoned aloud that I’d be at 100kg by the end of the year. He countered placidly by saying that I must find a manner of eating that I can live with for the rest of my life.

After I’d chimed in with my own words, Dr Nanda said that some people get disappointed with slow progress and revert to bad habits. If I feel hungry and need a snack he suggested that as well as the three brands of low-carb confections I was getting from the supermarket – delicious and filling and containing almost zero carbs – instead of a biscuit I could eat a handful of cheese or some nuts. This was advice I would take to heart and, in fact, was already following.

24 November

Weigh-in this morning gave a figure of 109kg. This day I noticed a peculiar feature of the Apple Health app. Usually, every morning before getting dressed I weigh myself but on this Tuesday I got a reading the first time of 109.4kg – which I thought strange since it was higher than the previous day’s – then after a bit used the loo and proceeded to remove my clothes and weigh-in again.

This time the reading was lower but the Health app now showed an average weight for this day. This is because, when entered, readings have a time flag, so putting in two figures separated by, say, 20 minutes, makes the app average the numbers to give a composite figure. Also, you cannot go back and change a figure once it is entered and, if you want to revise a reading, you can only enter a new figure. The app averages both figures to arrive at a third figure. The app’s makers settled on this compromise evidently in order to simplify the interface; if they’d made the app able to let you edit earlier readings it would’ve made the app more complex to use. However, it lets you enter a figure for a past day at a specific time. The FatSecret app doesn’t handle weight readings in this way, and allows you to edit a daily figure – but only on the day in question.

25 November

Morning weigh-in read 108.6kg. In the morning went to Coles and bought (see receipt below) tomatoes, mushrooms, baby spinach, cheddar cheese, gruyere cheese, sliced pastrami, sliced ham, bacon, mayonnaise, low-carb snacks, and flavoured sugarless mineral water.

28 November

Morning weigh-in read 108.4kg. Later, went to Coles and bought (see receipt below) shortcut bacon, an avocado, sliced pastrami, and sugarless flavoured mineral water.

29 November

Morning weigh-in read 108.3kg. Later went to Coles and bought (see receipt below) red Leicester cheese, apples, strawberries, Greek yoghurt, and flavoured sugarless mineral water.

Calorie intake for the week was, as follows:

Activity for the week was, as follows:

And macronutrient intake for the week:

This week I ate an average of 45g of carbs a day.