When A Clean Break Gets Dirty

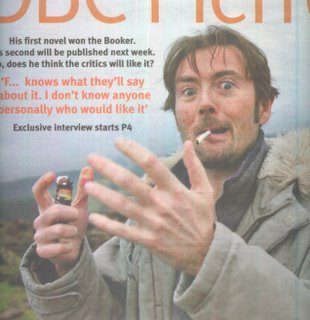

DBC Pierre has traversed the highway from obscurity to literary success — and global notoriety. Where will this forty-something author go from here?

A radical faction in a religious sect had planned to turn a nuclear power station into an atomic bomb. Stung by the ensuing publicity, the sect disclaimed all its tenets. After the event, it must forge a new path.

This brief synopsis of Kenzaburo Oe’s 2003 novel, Somersault, could apply to writer DBC Pierre’s life since that year, as it has traced a similar trajectory but, as in a photographic negative, with the tones inverted.

The explosive device in Pierre’s case was Vernon God Little, his first novel — a rapid and inspiring romp through the preposterous and poignant backstreets of suburban U.S.A. — which propelled him into the stratosphere, securing the Man Booker Prize. In 38 years, only one other first novel has ever won the prize. Global sales of the novel, including translations into 43 languages, are healthy at around 1.5 million.

Like the sect, Pierre stood — and stands — outside the mainstream. Before the life-changing event no-one knew he even existed. But with the release to mixed reviews of his second novel, the startling Ludmila’s Broken English, he must start to forge a new path.

It’s apparently not enough that the novel is so different, in subject, tone and structure, from its predecessor. “Well, there aren’t many writers who’ve had such an extraordinary life, so I suppose it’s inevitable,” said his London agent, Clare Conville. “And I think, sort of, a backlash is inevitable, his success, you know, was so incredible.”

Pierre was born Peter Finlay in Adelaide, grew up in Mexico, and lived a wayward life in the U.S., Australia, the Caribbean, and England. He now works in a secluded corner of Ireland. Almost without exception, commentators have expressed mixed feelings about his chequered past, coloured as it is by inglorious undertakings.

Winning the Booker, among the most prestigious prizes in the literary world, seems to have exerted a quantum of pressure on the 43-year-old to conform to our view of what an award-winning author should be. It is true that he has survived many adventures, from illegal importing of cars to drug abuse, from obtaining money under false pretences to domiciling in Ireland for tax reasons. (A interviewer recently added this to his list of sins. But while this latest accusation is also no doubt true, it is relatively venal compared to the rest).

For critics to accept that a new writer deserves their applause, the difficult second novel must be unquestionably good. This is. But in Pierre’s case it must also be demonstrably virtuous. And this is anything but. Like DBC Pierre himself, the novel is ‘dirty but clean.’ It is a frazzled and imaginative hurly-burly filled with intimations of mortality and Shakespearian phrases that confound expectations.

“I haven’t seen any of them,” said Pierre philosophically when asked about the reviews during a talk to promote the book in The Rocks with Sydney Writer’s Festival doyenne Caro Llewellyn. “It doesn’t matter. Well, first of all, I just feel lucky to have a job, anyway. So I’m not that fussed, but if those reviews came out when I was still writing it, that would be problematic. But there’s a timeline — and it’s easy to forget — that once you deliver a book it walks on its own feet, and I’m just not responsible for it. There’s nothing you can absolutely do any more, you can’t go back in and shift anything… it’s all after the fact. … You know, I had to take risks and try and become a good writer, as best I could. And that’ll take a while.”

At his previous appearance, for the 2004 Festival, the Sydney Theatre was filled. This time attendance was limited by organisers, and about 100 antipodean fans entered the Belgian Beer Café from the bright autumn sunlight.

Did he think the world is harder for people who don’t fit the mould, asked Llewellyn: “I’m still trying to figure that one out,” he said. “I certainly don’t think that your loose cannons and your explosive people roaming outside the herd are any danger at all to society. In fact they’re probably the mixers that keep the rest of us in some sort of cohesiveness. But I’m still wondering what the relative benefits are of sticking with the pack and just having a nice life versus… not quite getting things together and staying outside the edge of it. And it’s interesting… we need both of them anyway, really. Especially, if you’re a bit of an outsider you need the herd to come and pick up the pieces when you hit the wall. And they probably need something to look at on TV every night.”

Having lost his footing on numerous occasions, Pierre speaks from experience, and his attempt to distance himself from those outside the mainstream is unconvincing. But he is genuinely determined to succeed. “He’s very firmly sure about what he wants to do and how he wants to do it,” said Conville.

Pierre’s ‘radical faction’ remain his drive, imagination, and sense of humour — the qualities that launched his career and now propel him past the obstacles set in his path. He seems determined to make the best of things. Living always in foreign countries, he has felt an outsider all his life and he admitted that this has touched his work: “Since writing I have found that that’s really helpful, actually. It’s good.”

I bought a copy of Ludmila’s Broken English as soon as it became available and enjoyed it immensely. It is quite sufficient to upset him that others didn’t, yet he appears resigned to completing any number of about-turns, fulfilling the role of enfant terrible of modern publishing, his new work both awaited and bemoaned. But only a month after the novel’s release it generates almost 40 pages of Google-search results.

That’s a solid endorsement, especially for an outsider, and indicative of better things to come. Having faced new challenges since the initial detonation of fame, it’s not beyond the pale of probability that Pierre will experience further somersaults in his life. After all, Oe had to wait 36 years for his Nobel Prize.

2 comments:

I'm tempted by his work (and your review of it certainly encourages me to try some) but I have this impression, probably entirely false, that it's a lot of verbal pyrotechnics with no heart. Am I wrong? I do hope so.

Ludmila's Broken English got some very mixed reviews. Some reviewers were confused by his style in this new book. I thoroughly enjoyed it. There's a linked review by me that contains several quotes if you're interested -- the link's near the end of my feature.

I really meant what I said. I thought his style Shakespearean, very invigorating.

Post a Comment