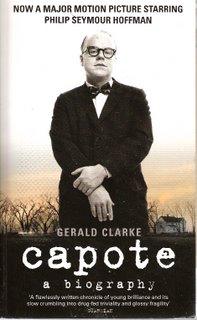

Review: Capote: A Biography, Gerald Clarke (1988)

Review: Capote: A Biography, Gerald Clarke (1988)I suppose if you enjoy gossip and the smart set, this book will very much appeal to you. If he weren’t a writer, I must admit, it would be the most deadly bore to read. For me, having read only one piece of narrative non-fiction, one novella and three short stories by Truman Capote (all of which were very good, of course), the tedium did set in once he had grown up. By the time he is twenty six years old and independent, his story becomes a never-ending parade of names and locations. Sicily with Cecil, Paris with Alice, Rome with Tennessee. Ho hum.

The early chapters are meatier. They cover his life with his psychopathic mother, who wanted to give him hormone injections to prevent him being a “fairy”. Wearing blue jeans and adopting attitude at school, where he refused to take gym classes, was also satisfying to read about. It is always a pleasure to discover, between the covers of a book, an outsider (Mon semblable, mon frere).

Once he has reached published success, however, the endless parade of parties and holidays in the south of Italy wears extremely thin. How can you compare his mother’s treatment of him in his minority to the trials of living in a hot hotel and suffering the carryings-on of a troupe of British soldiers, in Tangiers?

However, I decided to stick with it, to find out about the genesis of In Cold Blood (1965) and Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1958). There are some inklings early on. And the narrative has a way of shooting around, as Clarke follows each lead to its logical conclusion, often breaking out of a strictly chronological sequence.

Another weakness of the book (which however is very well-researched — it took 12 years to write) is the use of first names. Clarke will introduce a character, tell you who it is, and go on to something else. But when that character reappears you’ve most likely forgotten who it was. As a result, you suddenly find yourself reading about Sam or John or Andrew, and feel inadequate because you can’t (for the life of you) remember who they are. I think this is a failing. The author should compensate for a reader’s fallibility: repeat key details so that he or she can build up a meaningful picture. For aficionados, Clarke’s method no doubt works. For we neophytes, it’s a bit of a bore.

But Clarke stays largely on message, and his book is filled with small insights that add up to an interesting portrait of a man who liked to be loved. Or loved to be liked. Or something. To whit: his friendship with Cecil Beaton, the British photographer. Who eventually dumped him, as so many did.

Clarke is not a literary critic, and his study of Capote as a writer is frequently superficial. Society dramas take precedence over creative ones. The drama of his infatuation with Lee Radziwill, for example, reflects poorly on Capote, as if he had finally lost his sense of perspective. It is interesting, however, that Lee was such a loser, and that Capote sympathised and wanted to help. Here, it seems, was someone even lonelier than himself, and he appears determined to make something out of nothing. A creative act, says Clarke. A waste of time, we suspect. It does not reflect well on either of the two protagonists.

After the publication of In Cold Blood however, Capote’s need for reassurance, especially from the critics, reached a height that would actually prevent him from writing. He drank more, took more pills, and spent more time running around with his ‘swans’ than he did at his desk. Clarke tries to suggest that his childhood scarred him and that, now, at 41 years of age, it had come back to haunt him. But these purple passages, that attempt to pass blame, do not adequately justify the ‘downward spiral’ that Clarke annotates. Capote was, simply, in need of love beyond the power of others to provide it, and he paid for his obsession with his sanity, if not his life. Whether it was his mother who did this to him or not, I personally cannot say. And Clarke is not being honest when he affirms that it was.

To further affirm that writing In Cold Blood had damaged him is to compound the error by multiplying the causes. Capote cannot be held accountable for his own destiny, we are told, and it just does not wash. Because the chronology gets confused, I cannot remember if it was eight years or six that he spent writing the non-fiction novel. Whichever is the true number, I do not accept for a moment that it was the cause of his inability to write the next big thing, which Random House paid dearly for. Capote just seems unable to keep going due to a flawed character or, more probably, laziness. More desirous of adulation than excellence, he simply gave up the ghost.

The string of straight guys he conscripted into his adolescent fantasies also suggest he was losing it. Time after time he tried to gain some traction on the road to romance, and one after another he shucked these men off, unable to convince himself, in the end, that it was worth the effort. He delayed work. He let down business partners. He became an alcoholic and a wreck by the time he reached his late forties.

Or so it seems. But the publication of ‘La Cote Basque’ in Esquire in 1975, demonstrates where Truman’s real allegiances lie. He finds that many of the people he had trusted and who had trusted him, are outraged by the way he has portrayed them in the short story, which will become part of a novel at the time yet to be completed. It is a pungent episode, revealing the truth at the heart of the old saw that says you cannot ever trust writers. They will use you every time. In my eyes, however, it serves to extricate Capote from the slough of despond that had seemed to have engulfed him. It redeems him. If these idle wastrels he had surrounded himself with for so many years, and who had basked in the reflected glory from posterity and the populace that he delivered to their well-decorated dining rooms, cannot tolerate being exploited in his narratives, then they are not worthy of his attention. It is axiomatic that to complete their odysseys, writers must use whatever raw material is available, and I applaud Capote’s betrayal of their trust.

The bit clenched firmly between his teeth, Capote forges ahead with Answered Prayers, publishing further instalments in Esquire in 1976. After all, In Cold Blood, had been published for a decade and in the interim he had produced no major work.

Then Music for Chameleons shimmers on the horizon like a mirage that promises something more fecund, productive. It is a fleeting moment of calm and fruitfulness before the soundtrack to his life, Hotel California, resumes its steady rhythm.

Struggling with paranoid delusions, Capote, in 1981, is entering into the final phase of his life. We can finger the slimming stack of pages held between the thumb and forefinger of our right hand and consider the many opportunities to shine that were lost by this great writer who is now tightly shackled to a raft of substances that are sending him slowly around the bend. The bright applause that followed the publication of In Cold Blood has now dwindled to a distant echo. And freed now from considerations of the writer’s texts, Clarke can concentrate on the relationships, which is, finally, the ambit within which this biography excels.

1 comment:

Post a Comment