Markus Zusak is featured in the (sydney) magazine (a monthly supplement to The Sydney Morning Herald that appeared with yesterday's edition):

To come up with "preposterous ideas", the author of The Book Thief recommends stealing stories from everyday life.

When Markus Zusak visits a school to talk to the students about writing, the first thing he teaches them is how to be thieves. "I'll spend the first 15 minutes of a school visit talking about stealing," he says. "They ask about getting caught and I'll say, 'Everyone steals. Think of the nicest person you know' — they'll think of their mum — and I'll say, 'I'm telling you, she steals. Every time I go to the supermarket, I see someone's mum eating the grapes and the nuts.'" That's when the kids "start buzzing", says Zusak. "The teachers will try to calm them down but I say, 'Leave them. They're doing exactly what I want them to do — they're telling stories.'"

The stories don't have to be about stealing, he adds, but the point is that everyone can draw from their own experiences in order to create a compelling piece of writing. "You can steal stories from your own life." It seems apt for an author who has written a novel called The Book Thief, a bestseller about Liesel, a young girl growing up in Nazi Germany who becomes a literary kleptomaniac — and who has a Jewish fistfighter hiding in the basement of her house. "I gave it everything," he says. "It's like every piece of me, that book."

Zusak's fifth novel, The Book Thief was inspired by stories told to him by his mother, Lisa, who was born in Munich and witnessed the bombing of that city at the age of six, and by his father, Helmut, who grew up in Vienna. Zusak was particularly affected by his mother's recollections of an old Jewish man who couldn't keep up when he was being marched to Dachau by the Nazis. "A teenage boy ran inside and grabbed a piece of bread and this man fell to his knees thanking him. Then a soldier threw the bread away, whipped the old man for taking it and chased the boy down and whipped him as well. That story has everything in it — pure beauty and destruction. I was fascinated by that small percentage of people who helped during the war — not just the people who survived but the people who hid them."

Intriguingly, the book's narrator is a personification of Death. He's not so much a grim reaper as a vaguely endearing character who tells bad jokes and is more afraid of his victims than they are of him.

That may seem improbable but Zusak, now 31, is already a veteran of what he calls "preposterous ideas". His fourth book, The Messenger, a young adult's title being re-released this month by Picador, features "a dog who will only drink coffee with milk and sugar in it. But even in works like that there has to be an element of truth as well."

His quirky formula seems to be working. In the last decade he has been shortlisted for the Commomnwealth Writer's Prize and has won the NSW Premier's Literary Award, the Queensland Premier's Literary Award and the Children's Book Council Award of the Year. In March, USA Today said The Book Thief was "poised to become a classic".

But he hasn't grown accustomed to the accolades. "I grew up in the Shire," he laughs. "My dad's a house painter; my mum's a house cleaner. I didn't know anyone in publishing. I didn't even know a writer's festival existed."

Still, at age 16 he decided he was going to be a writer "and nothing was going to stop me". A bit of knocking about from his three older siblings helped fuel his ambition. "It comes from all those times when I was 'too small'. I thought, 'One day I'm going to show all of you bastards.'"

Zusak, whose wife, Dominika, is due to give birth in September, has amply fulfilled that brief. Now working on his sixth book, he was named one of The Sydney Morning Herald's best young Australian novelists in May.

On St Patrick's Day, he was in New York when Fox bought the rights to make The Book Thief into a film. Just hours earlier, he had appeared on Good Morning America — the upshot of which was that his book hit the number one spot on Amazon, albeit briefly. "I was outselling The Da Vinci Code for about six hours," he laughs. "You don't have many better days than that."

Friday, 30 June 2006

J.M. Coetzee's wonderful novel Disgrace is set to be filmed, reports The Australian:

THE Australian film-making team of writer-producer Anna-Maria Monticelli and director Steve Jacobs, together with Emile Sherman, son of South African-born Australians Gene and Brian Sherman, has secured actor John Malkovich to play the lead in the movie Disgrace, an adaptation of the Booker Prize-winning novel by J. M. Coetzee that goes to the heart of ethical complexities in modern South Africa.

Peter Ackroyd, the master storyteller of English civilisation, does it again. This time, it's Newton that he reveals in black and white. The book is recently published and promises to provide more illuminating factual evidence of high culture and aspiration in the land of the pork pie.

The Guardian has also published a brief review of this book, which I'm sure my father would enjoy reading. I'm going up to Queensland to visit my parents on Sunday, so I'll mention it to him then.

They write:

The Guardian has also published a brief review of this book, which I'm sure my father would enjoy reading. I'm going up to Queensland to visit my parents on Sunday, so I'll mention it to him then.

They write:

Isaac Newton probably wouldn't be the best role model for the aspiring mathematician. Newton famously grouched even about having his ideas published, because: "It would perhaps increase my acquaintance, the thing which I cheifly [sic] study to decline."

Thursday, 29 June 2006

This should be fun. Michael Winterbottom has just released Tristram Shandy: A Cock and Bull Story. Although I'm not a big film-goer, I relish the combination of a good novel and a good director. And since Winterbottom's 9 Songs was banned here when released some years ago, I'm even more determined to make the trek to the cinema. I'm on holidays next week, so hopefully they'll be screening it in Maroochydore.

"We just couldn't get anywhere with the script when we were thinking about only filming the book," Winterbottom says during a moment of quiet on the street. "The more we looked at the book it seemed that Sterne was playing around with the reader a lot, and the only way to deal with that was play around with the viewer by showing the problems of making a film.

"So we came up with the idea of Steve kind of juggling his girlfriend, the baby, the script, his obsession with the height of his shoe heels, the agent, his co-stars, even a tabloid reporter. It was a version of real life. You try to focus on important things, but all this other stuff is always going on, too."

Wednesday, 28 June 2006

The philosopher Fernando Savater on the fate of the printed page, from La Stampa, 28 June. According to the Wikipedia he is a “Spanish philosopher and essayist most famous for his popular books on ethics and his newspaper articles. Presently he is Philosophy professor at the Complutense University of Madrid.”

Books don’t die if they run, travel and cross the seas

Walking down the main street of Hay-on-Wye I started thinking about the strange, vagabond destiny of books. “Fata sunt belli” said — if my clumsy Latin doesn’t deceive me — the classics, before the birth of our language: minor and even great books have, each one, their own destiny, their idiosyncratic coming and going, written in the fatal twinkling of certain stars. They are the ones to determine (I still use metaphor, but I’m not superstitious yet) the direct or collateral feelings that these pages will engender, their marginalisation or their success — sometimes both, in different times — and also the multiplication of their interpretations. Or oblivion, pious and atrocious.

Hay-on-Wye is a small town in the English county of Herefordshire, in that green and pleasantly ordered border land next to Wales. A community of less than 1,500 inhabitants that boasts the amazing existence of around 50 bookshops, which are almost exclusively dedicated to antique and used books, at second- or third-hand.

It’s not a cemetery of literary elephants because books well looked-after don’t die even if they pass through many hands but, on the contrary, become richer and grow: like lovers who have loved too much… For over 10 years Hay has been home to a literary festival at which writers speak openly with their readers, poets declaim and scientists explain their theories, you can meet Nobel Prize-winners next to politicians or authors of bestsellers, and books, the most vigorous and technically advanced tool invented by humans, are celebrated in all possible ways. How many subjects can you write something about! Because a bookshop (or a library) is like a pharmacy: you can find legible remedies to all the ills of mankind, from ignorance to sorrow, and also magic potions that provide knowledge, happiness or erotic stimulation. And we must admit that there are also poisons…

I walked, therefore, along the main street of Hay on that sunny, balmy June morning thinking of the books that run, travel, fly and cross the seas. And the last occurrence of the show, that took place in January in Cartagena delle Indie, occurred to me. I forgot to say that, now, the literary event at Hay has “branches” in other cities, like the one in this Columbian town or, in the near future, in Segovia in Spain. During the festival of Cartagena I didn’t restrict myself to enjoying the justly famous tourist attractions of the place, but I also went to visit a school in the Nelson Mandela colony, a very poor sector that the tourist in search of beaches or colonial beauty has scarce interest in visiting. The heat was tremendous, but there was no running water: two or three times a week a water-truck arrived.

My guides showed me the shanties people live in, constructed from precarious and unmatched materials, and said: “See? These houses are made from ‘paroy’.” I could not understand what material they were referring to and, then, they explained: “We call them that because they’re “of today” (‘para hoy,’ in Spanish — ed.): tomorrow, perhaps, they’ll no longer be standing.” There were no macadam roads, no footpaths: they got to school in any way they could. The teachers hadn’t been paid for six months, but they overflowed with enthusiasm: they reminded me of those medieval monks who, on land sacked by barbarians, copied and watched their manuscripts in which was enshrined a defeated culture but one that would one day return to flower.

And here are the children: with dark skin or light, rippling with laughter, free, curious. They asked me about everything, with laughter and without cease: where I lived, what time I usually prefer to write, how I came up with ideas and whether I was engaged. Then they started dancing to show me how happy they were to be there. I was hardly able to utter a few words because I was overcome with emotion and — I have to say it — admiration. How exultant it was, that happiness, able to throw down walls of egotism and blindness! They needed everything, but they deserved much more. I noticed, at a certain point, that they had some copies of my books on their desks, tortured by long use but raised, even, to unmerited glory thanks to the benediction of so many little black hands. And I felt ridiculously proud.

For once it seemed to me that not everything was vanity or habit, that I could give something, offer a service where it was needed. A feeling that I had felt, at another time, in Guatemala while visiting a small bus that had been transformed into a movable library and I came across one of my works. Or when a colleague at the university showed me the photograph of the very modest house of a student in Guinea in which I had stayed one night: I glimpsed, on a shelf, the back of another of my works.

Launched on the ocean of uncertainty all these books whose limitations I know too well — a mixture of perplexity, ideas and dreams — had finally arrived home. I wish that you, brother readers, and also that I — seeing that our destiny is to be travellers and to never know the place that only occasionally we occupy — obtain, on the last day, a comfortable and useful corner in the great library of the universe.

Books don’t die if they run, travel and cross the seas

Walking down the main street of Hay-on-Wye I started thinking about the strange, vagabond destiny of books. “Fata sunt belli” said — if my clumsy Latin doesn’t deceive me — the classics, before the birth of our language: minor and even great books have, each one, their own destiny, their idiosyncratic coming and going, written in the fatal twinkling of certain stars. They are the ones to determine (I still use metaphor, but I’m not superstitious yet) the direct or collateral feelings that these pages will engender, their marginalisation or their success — sometimes both, in different times — and also the multiplication of their interpretations. Or oblivion, pious and atrocious.

Hay-on-Wye is a small town in the English county of Herefordshire, in that green and pleasantly ordered border land next to Wales. A community of less than 1,500 inhabitants that boasts the amazing existence of around 50 bookshops, which are almost exclusively dedicated to antique and used books, at second- or third-hand.

It’s not a cemetery of literary elephants because books well looked-after don’t die even if they pass through many hands but, on the contrary, become richer and grow: like lovers who have loved too much… For over 10 years Hay has been home to a literary festival at which writers speak openly with their readers, poets declaim and scientists explain their theories, you can meet Nobel Prize-winners next to politicians or authors of bestsellers, and books, the most vigorous and technically advanced tool invented by humans, are celebrated in all possible ways. How many subjects can you write something about! Because a bookshop (or a library) is like a pharmacy: you can find legible remedies to all the ills of mankind, from ignorance to sorrow, and also magic potions that provide knowledge, happiness or erotic stimulation. And we must admit that there are also poisons…

I walked, therefore, along the main street of Hay on that sunny, balmy June morning thinking of the books that run, travel, fly and cross the seas. And the last occurrence of the show, that took place in January in Cartagena delle Indie, occurred to me. I forgot to say that, now, the literary event at Hay has “branches” in other cities, like the one in this Columbian town or, in the near future, in Segovia in Spain. During the festival of Cartagena I didn’t restrict myself to enjoying the justly famous tourist attractions of the place, but I also went to visit a school in the Nelson Mandela colony, a very poor sector that the tourist in search of beaches or colonial beauty has scarce interest in visiting. The heat was tremendous, but there was no running water: two or three times a week a water-truck arrived.

My guides showed me the shanties people live in, constructed from precarious and unmatched materials, and said: “See? These houses are made from ‘paroy’.” I could not understand what material they were referring to and, then, they explained: “We call them that because they’re “of today” (‘para hoy,’ in Spanish — ed.): tomorrow, perhaps, they’ll no longer be standing.” There were no macadam roads, no footpaths: they got to school in any way they could. The teachers hadn’t been paid for six months, but they overflowed with enthusiasm: they reminded me of those medieval monks who, on land sacked by barbarians, copied and watched their manuscripts in which was enshrined a defeated culture but one that would one day return to flower.

And here are the children: with dark skin or light, rippling with laughter, free, curious. They asked me about everything, with laughter and without cease: where I lived, what time I usually prefer to write, how I came up with ideas and whether I was engaged. Then they started dancing to show me how happy they were to be there. I was hardly able to utter a few words because I was overcome with emotion and — I have to say it — admiration. How exultant it was, that happiness, able to throw down walls of egotism and blindness! They needed everything, but they deserved much more. I noticed, at a certain point, that they had some copies of my books on their desks, tortured by long use but raised, even, to unmerited glory thanks to the benediction of so many little black hands. And I felt ridiculously proud.

For once it seemed to me that not everything was vanity or habit, that I could give something, offer a service where it was needed. A feeling that I had felt, at another time, in Guatemala while visiting a small bus that had been transformed into a movable library and I came across one of my works. Or when a colleague at the university showed me the photograph of the very modest house of a student in Guinea in which I had stayed one night: I glimpsed, on a shelf, the back of another of my works.

Launched on the ocean of uncertainty all these books whose limitations I know too well — a mixture of perplexity, ideas and dreams — had finally arrived home. I wish that you, brother readers, and also that I — seeing that our destiny is to be travellers and to never know the place that only occasionally we occupy — obtain, on the last day, a comfortable and useful corner in the great library of the universe.

Tuesday, 27 June 2006

Rupert Murdoch is aware of the blogosphere. In comments delivered after a meeting with government ministers at Kirribilli House, the residence of the prime minister, and reported in his flagship broadsheet, The Australian, the media mogul gave voice to his interest in the Internet.

"I feel very confident that good, sound, honest journalism will prevail in the long term — even though it may not be delivered on destroyed trees," Mr Murdoch said.

"Broadband will bring about tremendous choice for people about where they get their information, what information they want, and where they can put their views out.

"There are millions and millions of new writers on the internet, mainly writing rubbish, but a lot are writing words of wisdom. As you find your way around it, it is a magnificent thing to see."

Treasures of Cambridge are to be catalogued for online access. The New Zealand Herald ran this story recently, detailing what has been found in the Cambridge University library tower, a "big Stalinist building of eight or nine storeys".

First editions of what are now classics abound among literary work that was once considered second-rate but is now highly valued. Jim Secord, "a professor of the history of science who has explored the contents of the tower" says:

"If you like browsing in old bookshops then this is about 10 times better."

The story originally appeared in The Independent.

The Scotsman has run a review of Mark Bowden's latest work. Dubbing him "the reigning champion of narrative non-fiction," Alex Massie suggests that the book, entitled Guests of the Ayatollah, is timely. It deals with the hostage crisis of 1979.

Bowden sometimes becomes bogged down by the demands of juggling the stories of the hostages, their captors, and the diplomatic and military efforts to end their agony, but still produces a narrative that illuminates the divide between Persia and the west.

Bowden has a blog dedicated to the book where you can ask questions or make points about facts.

The New York Times ran a review of the same book in May. James Traub says: "Guests of the Ayatollah is, at bottom, a story of mutual incomprehension."

Sunday, 25 June 2006

Interview: Zadie Smith (in Italian journal La Stampa, 20 June)

Yes, I'm cute, but what about my talent

Giovanna Zucconi: Have you ever been to Rome before, Ms Smith?

Zadie Smith: No, but my husband and I will live in Rome for seven months from November.

GZ: Oh, with your husband the poet Nick Laird, with whom you are writing a musical on Kafka. And how do you end up in Rome after London, after Harvard? For you, who reads publicly all over the world, is there a difference between reading, let’s say, on an American campus or among the Roman ruins?

ZS: It’s impossible to say until I’ve had experience of Rome and its ruins. At first glance, I think that some things in Italy will be more attractive than elsewhere.

GZ: We don’t often realise it, around here, but anyway… Do you like to appear in public? How do you maintain a balance between the public and the private life?

ZS: I don’t have a public identity. I don’t like the notion of ‘the public,’ it’s a reductive term. At readings I read in front of many individuals, then I go home to my house and they to theirs.

GZ: To be a writer is also a job. Interviews, autographs, prizes, readings. Has your attitude changed toward these professional rites and obligations, compared to in the beginning?

ZS: I don’t have any attitude. I only think about getting back to my study and writing. The rest happens for a few months every few years.

GZ: Even so, isn’t it true that these days being a writer has a lot to do with the ‘look,’ with showing yourself, with appearance…

ZS: Writing a book has nothing to do with the ‘look’ or with appearance. These things are for journalists and the press. When I write I depend only on my brain, and when I read I don’t care about the look of the writer. Either you can write or you can’t, and if someone sells a few extra copies of their book because they’ve got a nice face means nothing. Soon I’ll be forty, then fifty, then sixty, I’ll keep on writing and you, hopefully, will stop asking ridiculous questions about my appearance.

GZ: But writing a book and being a writer are two different things, you can’t deny it. Zadie Smith has been ‘sold’ as a ‘personality’ even before writing the first book (attractive, multiethnic background, liveliness), and you know it: admitting it takes nothing away from your books, but such as it is, we’ll let it go. You said that novelists are not only intellectuals, that a basic literary talent is the emotional intuition. What intuition were you thinking of? Maybe a feeling for the spirit of the times? That’s required to write the ‘right’ novel at the ‘right’ moment?

ZS: What interests me is writing a great novel before I die. The spirit of the times has nothing to do with literature, if you want to get into that you’ve got to be a pop star.

GZ: But you are treated like a pop star, including the paparazzi and the press frenzy: won’t you ever be asked why? Have you never reread White Teeth, even just to understand how that book at that time clicked with so many people?

ZS: Never.

GZ: In the judgement of the Orange Prize, which you just won for On Beauty, they say that the novel is a “literary tour de force”. What does that mean? It's satisfying to read…

ZS: I don’t know. It was a lot of fun to write, three years shut up in my room is, for me, the pleasantest of experiences.

GZ: Success always means quality?

ZS: If fifty million people buy something it doesn’t mean that it’s either good or bad. Eminem is talented and an enormous success, Kafka had enormous talent but with no success. For me, my books have sold well but if I’m a good writer — that is, if my books are good — individual readers will decide, and future readers.

Comment: There seemed to be a lot of friction between them. She was quite prickly, I thought. But the interviewer was treating her like a megastar, rather than a serious intellectual.

Yes, I'm cute, but what about my talent

Giovanna Zucconi: Have you ever been to Rome before, Ms Smith?

Zadie Smith: No, but my husband and I will live in Rome for seven months from November.

GZ: Oh, with your husband the poet Nick Laird, with whom you are writing a musical on Kafka. And how do you end up in Rome after London, after Harvard? For you, who reads publicly all over the world, is there a difference between reading, let’s say, on an American campus or among the Roman ruins?

ZS: It’s impossible to say until I’ve had experience of Rome and its ruins. At first glance, I think that some things in Italy will be more attractive than elsewhere.

GZ: We don’t often realise it, around here, but anyway… Do you like to appear in public? How do you maintain a balance between the public and the private life?

ZS: I don’t have a public identity. I don’t like the notion of ‘the public,’ it’s a reductive term. At readings I read in front of many individuals, then I go home to my house and they to theirs.

GZ: To be a writer is also a job. Interviews, autographs, prizes, readings. Has your attitude changed toward these professional rites and obligations, compared to in the beginning?

ZS: I don’t have any attitude. I only think about getting back to my study and writing. The rest happens for a few months every few years.

GZ: Even so, isn’t it true that these days being a writer has a lot to do with the ‘look,’ with showing yourself, with appearance…

ZS: Writing a book has nothing to do with the ‘look’ or with appearance. These things are for journalists and the press. When I write I depend only on my brain, and when I read I don’t care about the look of the writer. Either you can write or you can’t, and if someone sells a few extra copies of their book because they’ve got a nice face means nothing. Soon I’ll be forty, then fifty, then sixty, I’ll keep on writing and you, hopefully, will stop asking ridiculous questions about my appearance.

GZ: But writing a book and being a writer are two different things, you can’t deny it. Zadie Smith has been ‘sold’ as a ‘personality’ even before writing the first book (attractive, multiethnic background, liveliness), and you know it: admitting it takes nothing away from your books, but such as it is, we’ll let it go. You said that novelists are not only intellectuals, that a basic literary talent is the emotional intuition. What intuition were you thinking of? Maybe a feeling for the spirit of the times? That’s required to write the ‘right’ novel at the ‘right’ moment?

ZS: What interests me is writing a great novel before I die. The spirit of the times has nothing to do with literature, if you want to get into that you’ve got to be a pop star.

GZ: But you are treated like a pop star, including the paparazzi and the press frenzy: won’t you ever be asked why? Have you never reread White Teeth, even just to understand how that book at that time clicked with so many people?

ZS: Never.

GZ: In the judgement of the Orange Prize, which you just won for On Beauty, they say that the novel is a “literary tour de force”. What does that mean? It's satisfying to read…

ZS: I don’t know. It was a lot of fun to write, three years shut up in my room is, for me, the pleasantest of experiences.

GZ: Success always means quality?

ZS: If fifty million people buy something it doesn’t mean that it’s either good or bad. Eminem is talented and an enormous success, Kafka had enormous talent but with no success. For me, my books have sold well but if I’m a good writer — that is, if my books are good — individual readers will decide, and future readers.

Comment: There seemed to be a lot of friction between them. She was quite prickly, I thought. But the interviewer was treating her like a megastar, rather than a serious intellectual.

Censorship has gone mad in North Carolina. The Guardian in the U.K. has published a short piece about the banning of the Cassell Dictionary of Slang in local schools. The compiler of the book, Jonathon Green, responded equably enough:

The group responsible is called Called2Action.

But Catharine Lumby, head of Sydney University's Media and Communications Department, says there's nothing to worry about. In an article published in the weekend supplement goodweekend — which is distributed along with The Sydney Morning Herald — and aimed squarely at politicians and those in the community who have made comments recently on education issues, and who say that the curricula in schools are being 'dumbed down' and infected by postmodern influences, she observes that:

She says that teaching kids through media such as Buffy the Vampire Slayer is just as valid as teaching them through the classics. But she also says there is no correlation between what kids read and how they behave. And so claims by groups such as Called2Action are baseless:

So it's hardly likely that The Cassell Dictionary of Slang is going to cause youths to become disaffected and take drugs. These right-wing evangelical Christians — and we have plenty of them in this country, too — are just incredible. In fact, a family that bought this book and studied it along with their kids would have a lot of fun:

"I'm very flattered," said Mr Green. "It's not exactly book-burning but, in the great tradition of book censorship, there never seems to be the slightest logic to it."

The group responsible is called Called2Action.

But Catharine Lumby, head of Sydney University's Media and Communications Department, says there's nothing to worry about. In an article published in the weekend supplement goodweekend — which is distributed along with The Sydney Morning Herald — and aimed squarely at politicians and those in the community who have made comments recently on education issues, and who say that the curricula in schools are being 'dumbed down' and infected by postmodern influences, she observes that:

The ability to appreciate complex works of art and literature is a valuable skill, but a great source of pleasure for a minority of people. It was ever thus. Our schools should certainly give all students the opportunity to develop that kind of refined sensibility. But let's not kid ourselves that most Australian teenagers in the 1960s were lying around under trees quoting Milton and Wordsworth.

She says that teaching kids through media such as Buffy the Vampire Slayer is just as valid as teaching them through the classics. But she also says there is no correlation between what kids read and how they behave. And so claims by groups such as Called2Action are baseless:

[If] we look at the research into which kids are most at risk of becoming abused, violent, drug-addicted or winding up in jail, it's clear that popular culture has very little to do with it. One of the most comprehensive Australian reports ever done into the causes of violence in Australian society, published in 1990 by the Australian Institute of Criminology, put media influences at the very bottom of a long list which begins with the influence of family and economic equality. And while there is understandable concern that it's children most at risk who are most likely to be vieweing media unsupervised, it is countered by research showing that the place they are most likely to be learning antosocial behaviour is out on the streets.

So it's hardly likely that The Cassell Dictionary of Slang is going to cause youths to become disaffected and take drugs. These right-wing evangelical Christians — and we have plenty of them in this country, too — are just incredible. In fact, a family that bought this book and studied it along with their kids would have a lot of fun:

It covers the recorded lexicon of English slang from the Elizabethan period down to the present day. It includes rhyming slang, street slang, idioms, colloquialisms, and even some standard English terms where these have arisen out of slang. And not only British slang, but also that of other English-speaking countries, including North America, South Africa, the anglophone Caribbean, and Australasia, though not India.

Saturday, 24 June 2006

Ben Naparstek is “a Melbourne literary journalist and arts/law student. He writes for The Age, The Jerusalem Post and The London Times,” according to a Gleebooks Web page.

He had the good fortune to interview Haruki Murakami, whose new collection of short stories, Blind Willow, Sleeping Woman is due to be released here in July. I’ve just pre-ordered a copy.

Murakami spends a lot of time in the United States teaching: he holds a writer’s fellowship at Harvard. But he meets with Naparstek in Tokyo. It’s not altogether evident why he says this:

“I feel I have a responsibility as a novelist to do something.”

But presumably it has to do with politics in Japan.

Yet he refuses to fulfil the typical public duties of writers — participating in talk shows, judging panels and literary festivals — and declines all requests for television and telephone interviews.

This begs the question: why is this isolated creature now talking with an Australian journalist? The new collection of short stories must be the catalyst. Maybe he has something in his contract that obliges him to participate in interviews close to the release date of new books.

Having been weaned on foreign fiction, and being a dedicated translator of it for years, it’s no surprise that Murakami — born in 1949 — says things like this:

“I wasn’t interested in working for a big company like Toyota or Sony. I just wanted to be independent. But that’s not easy. In this country, if you don’t belong to any group, you’re almost nothing. Among the many values in life, I appreciate freedom most,”

Having lived for many years in Japan myself, I can attest to the truth of what he says. Australia is a much more developed country than Japan, and our emphasis on the individual — mature liberal humanism, if you like — is one reason for this.

His fabulistic style is defended at the end of the interview:

“You know the myth of Orpheus,” Murakami says. “He goes to the underworld to look for his deceased wife, but it’s far away and he has to undergo many trials to get there. There’s a big river and a wasteland. My characters go to the other world, the other side. In the Western world, there is a big wall you have to climb up. In this country [Japan], once you want to go there, it’s easy. It’s just beneath your feet.”

The ‘floating world’ re-emerges as a paradigm to describe the reality of his enigmatic country.

Friday, 23 June 2006

Incredible. Fantastically rich woman PhD-holder buys publishing gem and goes into therapy.

She now owns Granta, one of the most prestigious publishing houses in the English-speaking world. From Tetra Pak to terrifically well-connected, it seems like a dream. What wouldn't one do?

But emotionally crippled? Crikey. Let me try it out. Give ME some. We'll see how I fare. Probably pretty well. I'm willing to try.

I can see that a philanthropist might think they could do an awful lot of good with an imprint possessing the cachet of Granta. After all, it's published some of the leading names in literature (before they became famous). The only problem I have with the magazine is that their Web site uses Times font. I hate Times in online contexts. As you may have noticed, the font used on this blog is Verdana — by far the best font for online publication. I generally rate Sites that use Verdana very highly. Much better than Ariel, another popular online font.

Inheriting is a funny thing. It confers immense privilege, but also delegitimises: Rausing apparently finds being referred to as the "Tetra Pak heiress", with its implication that any intellectual interest is dilettantism, infuriating. She has said that when she was younger, an aspiring academic living in a dingy London flat, she hid the fact of her wealth. Eventually, she sought therapy because: "I wanted to be who I was and didn't want to hide anything any more. I know people who are emotionally crippled by money they inherited."

She now owns Granta, one of the most prestigious publishing houses in the English-speaking world. From Tetra Pak to terrifically well-connected, it seems like a dream. What wouldn't one do?

But emotionally crippled? Crikey. Let me try it out. Give ME some. We'll see how I fare. Probably pretty well. I'm willing to try.

I can see that a philanthropist might think they could do an awful lot of good with an imprint possessing the cachet of Granta. After all, it's published some of the leading names in literature (before they became famous). The only problem I have with the magazine is that their Web site uses Times font. I hate Times in online contexts. As you may have noticed, the font used on this blog is Verdana — by far the best font for online publication. I generally rate Sites that use Verdana very highly. Much better than Ariel, another popular online font.

Thursday, 22 June 2006

Errol Simper is a star. He's also a bloody good journalist. In today's 'Media' supplement — a regular Thursday offering from The Australian — he outlines the case for and against the likelihood of Keith Windschuttle making waves on the ABC board.

Quentin Dempster, the succinct host of the ABC's Friday-night staple, Stateline, discusses the digital media options the ABC can use to increase its income.

Another article, published in the opinion page of one of the broadsheets this week (can't remember which one), suggested that by conscripting the historian into the ABC stable, the broadcaster had effectively gagged him.

But these are interesting points of view from two of Australia's most experienced media players. We'll see if Windschuttle continues calling elements of the national broadcaster Marxists, and succeeds in altering the trajectory of this important institution.

Robert Manne, a former editor of Quadrant — the right-leaning magazine for which Windschuttle, [journalist Janet] Albrechtsen and [anthropologist Ron] Brunton have written — welcomed Windschuttle with this: "The Howard Government is in the pocket of the (commercial) television networks. They will never agree to advertising on the ABC. It is his (Windschuttle's) program, however, for an ideological purge of the ABC, if he forms an alliance with the other right-wing heavy-hitters on the board, that is likely eventually to succeed."

Quentin Dempster, the succinct host of the ABC's Friday-night staple, Stateline, discusses the digital media options the ABC can use to increase its income.

KEITH Windschuttle on the ABC board? It is all highly diverting and a bit of a hoot. But when the digital revolution is transforming online, print, radio and television media globally, what Australia desperately needs is a board that understands the exciting possibilities for enhancing the quality, programming range, innovation, reach, professional training and public value of the ABC.

And all we get from the federal Government is tired, old, adversarial, party-political patronage and ideological influence peddling.

Another article, published in the opinion page of one of the broadsheets this week (can't remember which one), suggested that by conscripting the historian into the ABC stable, the broadcaster had effectively gagged him.

But these are interesting points of view from two of Australia's most experienced media players. We'll see if Windschuttle continues calling elements of the national broadcaster Marxists, and succeeds in altering the trajectory of this important institution.

Popped into The Co-op Bookshop on the off-chance of a sale and found five books to add to my collection.

Struck it lucky. There were three tables of sale books, heavily discounted. I really don’t know why I’m buying more books. I purchased 11 books on sale three weeks ago and four more two weeks ago. Today’s offerings were mainly non-fiction titles and, this being a university bookshop, many were of an esoteric cast. But I found a bunch of appealing titles to add to my collection.

I’ve got three bookshelves. All are full. The big one in my study has shelves that are spaced too far apart for normal-sized books. So to accommodate new arrivals, I’m stacking them on top of the books already placed on the shelves. I’m buying a new unit in August from Claphams Furniture in Lane Cove. (They make them up to-size using an external contractor.) All these new purchases will probably already half-fill the new bookshelf when it arrives.

On the sale tables each book had a discount sticker. But because I’m a member of the co-op, when I reached the check-out they deducted an additional 75% off the sale price. Bingo.

The five books I picked up for just under $17 are:

The Transit of Venus, Shirley Hazzard (1980)

Player Piano, Kurt Vonnegut (1952)

Three Dollars, Elliot Perlman (1998)

Left Right Left: Political Essays 1977-2005, Robert Manne (2005)

The Alphabet Versus the Goddess: The Conflict Between Word and Image, Leonard Shlain (1998)

So now I've got tons of stuff to read when I go on holiday in July. Any suggestions on where to start?

Struck it lucky. There were three tables of sale books, heavily discounted. I really don’t know why I’m buying more books. I purchased 11 books on sale three weeks ago and four more two weeks ago. Today’s offerings were mainly non-fiction titles and, this being a university bookshop, many were of an esoteric cast. But I found a bunch of appealing titles to add to my collection.

I’ve got three bookshelves. All are full. The big one in my study has shelves that are spaced too far apart for normal-sized books. So to accommodate new arrivals, I’m stacking them on top of the books already placed on the shelves. I’m buying a new unit in August from Claphams Furniture in Lane Cove. (They make them up to-size using an external contractor.) All these new purchases will probably already half-fill the new bookshelf when it arrives.

On the sale tables each book had a discount sticker. But because I’m a member of the co-op, when I reached the check-out they deducted an additional 75% off the sale price. Bingo.

The five books I picked up for just under $17 are:

The Transit of Venus, Shirley Hazzard (1980)

Player Piano, Kurt Vonnegut (1952)

Three Dollars, Elliot Perlman (1998)

Left Right Left: Political Essays 1977-2005, Robert Manne (2005)

The Alphabet Versus the Goddess: The Conflict Between Word and Image, Leonard Shlain (1998)

So now I've got tons of stuff to read when I go on holiday in July. Any suggestions on where to start?

Wednesday, 21 June 2006

At Sarsaparilla and also on her own blog, Kerryn Goldsworthy has highlighted the paucity of fiction about real things in Australia at the moment. "Where, [journalist and historian David Marr] more or less asked, was the Australian Coetzee or McEwan?" She points out that he wanted "fiction about the conditions and the values of contemporary Australian life".

Overland, which blogger TimT says on Intersecting Lines is "not just leftish, it's far to the left of the Labor Party", has just posted a story by Anthony Macris on its Web site. It's about a young Australian man living in London in 1991, surrounded by the images and feelings of Operation Desert Storm. It also treats issues of consumerism and love. Macris' style is hypnotic: you are dragged into the consciousness of the main character inexorably, you see the evidence of consumer culture gone berserk, you wonder about the affair that might reveal itself if you travel with him to Brisbane.

This is fiction that addresses real issues. And his literary pedigree should work to attract readers. Macris was named by The Sydney Morning Herald as one of its Australian Best Young Novelists in 1998 and published Capital: Volume One in 1997. It's a good read for anyone who enjoys McEwan or Coetzee. Somewhere between Simon and Carey.

The Overland story is an excerpt from his upcoming book Capital: Volume One, Part Two. Here's a clip:

Another piece from the book is available on the Web site of the French journal le Passant Ordinaire.

Give him a try, tell us what you think.

Overland, which blogger TimT says on Intersecting Lines is "not just leftish, it's far to the left of the Labor Party", has just posted a story by Anthony Macris on its Web site. It's about a young Australian man living in London in 1991, surrounded by the images and feelings of Operation Desert Storm. It also treats issues of consumerism and love. Macris' style is hypnotic: you are dragged into the consciousness of the main character inexorably, you see the evidence of consumer culture gone berserk, you wonder about the affair that might reveal itself if you travel with him to Brisbane.

This is fiction that addresses real issues. And his literary pedigree should work to attract readers. Macris was named by The Sydney Morning Herald as one of its Australian Best Young Novelists in 1998 and published Capital: Volume One in 1997. It's a good read for anyone who enjoys McEwan or Coetzee. Somewhere between Simon and Carey.

The Overland story is an excerpt from his upcoming book Capital: Volume One, Part Two. Here's a clip:

A small crowd gathers around you in front of the television. You stand there watching, transfixed. The helicopter sequence ends. Suddenly you are on the ground, right in the thick of it. You all go together into the slaughter. The shots change frequently, indicating heavy editing. That’s all that’s left of the dead, these cuts from one image to the next. The camera studies the scene. It soon gets bored with vehicles riddled with bullet holes, with shattered axles and engines spilling from under bonnets like entrails. It turns its attention to the loot, begins to pick out ghoulish contrasts. There seems to be no lack of them. The top half of a washing machine, its bottom half torn away, rests on the sand next to a gleaming mortar shell, seemingly unspent. A car door, its paint blistered off, its window a drip of molten silicon, forms the backdrop to a carton of Marlboro, a bottle of Chanel N°5, and a large-scale model of a black racing car. A blackened, mangled heap of metal, the long gun barrel that rises up out of it indicating it used to be an artillery gun, has a large double mattress leaning against it, more or less intact. And on it goes. It soon becomes apparent that there’s virtually nothing the Iraqis haven’t tried to steal: power tools, air-conditioning units, entire racks of women’s dresses and men’s suits, cartons of washing powder, computers, stereos, VCRs, cots, prams, toys. Everywhere there are televisions. The editor of the report has saved these for last. The shots are so clear you can read the brand names: Panasonic, Sharp, NEC, and of course Sony, everywhere there are Sonys. Some of the televisions have their screens blown out, others are in perfect condition, lying there in the desert as if they were waiting to be turned on.

The crowd around you has grown so large that a salesman comes over. He takes one look at the screen, then discreetly walks away. A few seconds later the channel changes. The desert highway is replaced by a young woman on the studio set of a kitchen. She’s wearing a tight, low-cut top. She beams and talks and shreds carrots. You feel a small shock go through the crowd, as if you’ve all just woken up from a deep trance. Everyone quickly disperses, and the buying mood immediately fills the store again. The man standing next to you, however, lingers a moment. He’s probably in his mid-fifties, judging from his long grey beard. “Bloody disgrace,” he mutters, half to you, half to the woman on the widescreen TV who leans forward to peep under a saucepan lid, at the same time offering you a generous helping of cleavage.

You turn around and walk straight out of the store. Now doesn’t seem the time to get a Discman.

Another piece from the book is available on the Web site of the French journal le Passant Ordinaire.

Give him a try, tell us what you think.

Monday, 19 June 2006

The Australia Council for the Arts is the premier funding body for the liberal arts in this country. It provides much-needed funds for start-up activities. I was once involved in a small magazine (we only lasted one issue) that received funds from them. Now, a new chairman has been appointed to the Literature Board.

Imre Saluszinsky is well known to readers of The Australian, one of the leading broadsheets here and the flagship of Rupert Murdoch's News Ltd. He writes intelligently, mainly on political topics. But he's also involved in the magazine Quadrant, which is considered to be right-wing in outlook. This is what has caused consternation in some quarters.

Accompanying Saluszinsky's appointment recently has been the move of controversial historian Keith Windschuttle to the ABC's board.

These two appointments have caused a lot of anguish and gnashing of teeth among liberal (left-wing) intellectuals. Windschuttle is a regular contributor to Quadrant, where Saluszinsky is a member of the editorial advisory board.

Well, I vote for The Greens at both state and federal levels and I buy Quadrant. It's a great magazine that takes public life seriously and publishes new fiction every month. I was a bit surprised that Phillip Adams didn't bring the magazine into the discussions of the panel of New Yorker staff who visited Sydney for the Writer's Festival last month. But being an unregenerate leftie, it wasn't ever likely.

Imre Saluszinsky is well known to readers of The Australian, one of the leading broadsheets here and the flagship of Rupert Murdoch's News Ltd. He writes intelligently, mainly on political topics. But he's also involved in the magazine Quadrant, which is considered to be right-wing in outlook. This is what has caused consternation in some quarters.

Accompanying Saluszinsky's appointment recently has been the move of controversial historian Keith Windschuttle to the ABC's board.

These two appointments have caused a lot of anguish and gnashing of teeth among liberal (left-wing) intellectuals. Windschuttle is a regular contributor to Quadrant, where Saluszinsky is a member of the editorial advisory board.

Well, I vote for The Greens at both state and federal levels and I buy Quadrant. It's a great magazine that takes public life seriously and publishes new fiction every month. I was a bit surprised that Phillip Adams didn't bring the magazine into the discussions of the panel of New Yorker staff who visited Sydney for the Writer's Festival last month. But being an unregenerate leftie, it wasn't ever likely.

Review: The Ice-Shirt, William T. Vollmann (1990)

Dewey Decimal Classification: 813.5 V924 J2 1

In 1993, Vollmann responded to a question put to him by an interviewer about his “absorption as a kid in books”: “My primary world is just this one basic "dream world" that I've been in from the time I was a kid.”

Another online piece describes the Seven Dreams: A Book of North American Landscapes series of books as “a historicofictional account of the settlement of North America”. The Ice-Shirt constitutes volume one in the series. It is wonderful. In it, one reviewer says, he “encourages his readers to enter a time when myth and history overlap”.

A New York Times review is available for this book. It makes much of the American aspect of the novel. But the trip that the overweening woman Freydis and her compatriots from Greenland — another colony of the Norse Vikings — actually make to Vineland (or Wineland, as it is alternatively dubbed in the book) only starts half-way through. There are also many stories of other Greenlanders. Stories of outlawry, settlement, disease, family, step-children and more are thrust forth into the reader’s consciousness by Vollmann’s fine prose. And fine it certainly is. More than fine: superfine. It is shot through with poetry, peppered with clusters of Shakespearean compound nouns, mostly hyphenated, that raise the narrative to a level that can encompass themes of shape-changing and magic — the ‘trolls’ or Skraelings the settlers meet are endowed with magical powers — that accompany the Greenlanders on their adventures.

Like Jose Saramago, there is also much dry humour to enjoy in this book. Although a tale of adventure, the irony of many utterances works to bring the narrative down from the heights of poetry to the level of the every-day. This is satisfying and apt, and allows us to get close to the feelings of individual characters, regardless of their proximity to the other-worldly or their distance from us in time. As in Saramago’s excellent Balthasar and Blimunda, there is magic that can become real: a flying machine in Portugal that levitates using the power of people’s souls or a god with BLACK HANDS (the capitals dot the pages) named AMORTORTAK living in the wastes of the icy north can coexist with living, breathing humans. In this sense, Vollmann adheres to the fabulist tendency of much modern fiction, stretching from Gabriel Garcia Marquez to Haruki Murakami. And is he up to the demands of such exalted company? Yes, I say. He is. Very much so.

Will I be purchasing more work by Vollmann? Absolutely. It is also of interest to me that these dream worlds derive from the same pen that writes about prostitutes and war zones. His output is Herculean, but the quality is extremely high. Is Vollmann himself satisfied with this ambitious book?

“The first three-quarters of The Ice-Shirt are OK. I think that the last quarter I'd do differently. I was still trying to figure out how to mix history and fiction as I went. That was the first attempt at the seven. It was harder with The Ice-Shirt. I wish that I had more money too. For instance, I would've liked to have gone to Norway and Sweden for that one. If I had, that part would have been longer.” This from an interview at McSweeney’s, who in 2003 published his magisterial, seven-volume work, Rising Up and Rising Down: Some Thoughts on Violence, Freedom and Urgent Means, which has been dubbed "a moral calculus for violence". It was originally published for $US120.00 but now sells second-hand for three or four times that on Amazon.

Have you read any books by Vollmann? What do you think of his work?

Dewey Decimal Classification: 813.5 V924 J2 1

In 1993, Vollmann responded to a question put to him by an interviewer about his “absorption as a kid in books”: “My primary world is just this one basic "dream world" that I've been in from the time I was a kid.”

Another online piece describes the Seven Dreams: A Book of North American Landscapes series of books as “a historicofictional account of the settlement of North America”. The Ice-Shirt constitutes volume one in the series. It is wonderful. In it, one reviewer says, he “encourages his readers to enter a time when myth and history overlap”.

A New York Times review is available for this book. It makes much of the American aspect of the novel. But the trip that the overweening woman Freydis and her compatriots from Greenland — another colony of the Norse Vikings — actually make to Vineland (or Wineland, as it is alternatively dubbed in the book) only starts half-way through. There are also many stories of other Greenlanders. Stories of outlawry, settlement, disease, family, step-children and more are thrust forth into the reader’s consciousness by Vollmann’s fine prose. And fine it certainly is. More than fine: superfine. It is shot through with poetry, peppered with clusters of Shakespearean compound nouns, mostly hyphenated, that raise the narrative to a level that can encompass themes of shape-changing and magic — the ‘trolls’ or Skraelings the settlers meet are endowed with magical powers — that accompany the Greenlanders on their adventures.

Like Jose Saramago, there is also much dry humour to enjoy in this book. Although a tale of adventure, the irony of many utterances works to bring the narrative down from the heights of poetry to the level of the every-day. This is satisfying and apt, and allows us to get close to the feelings of individual characters, regardless of their proximity to the other-worldly or their distance from us in time. As in Saramago’s excellent Balthasar and Blimunda, there is magic that can become real: a flying machine in Portugal that levitates using the power of people’s souls or a god with BLACK HANDS (the capitals dot the pages) named AMORTORTAK living in the wastes of the icy north can coexist with living, breathing humans. In this sense, Vollmann adheres to the fabulist tendency of much modern fiction, stretching from Gabriel Garcia Marquez to Haruki Murakami. And is he up to the demands of such exalted company? Yes, I say. He is. Very much so.

Will I be purchasing more work by Vollmann? Absolutely. It is also of interest to me that these dream worlds derive from the same pen that writes about prostitutes and war zones. His output is Herculean, but the quality is extremely high. Is Vollmann himself satisfied with this ambitious book?

“The first three-quarters of The Ice-Shirt are OK. I think that the last quarter I'd do differently. I was still trying to figure out how to mix history and fiction as I went. That was the first attempt at the seven. It was harder with The Ice-Shirt. I wish that I had more money too. For instance, I would've liked to have gone to Norway and Sweden for that one. If I had, that part would have been longer.” This from an interview at McSweeney’s, who in 2003 published his magisterial, seven-volume work, Rising Up and Rising Down: Some Thoughts on Violence, Freedom and Urgent Means, which has been dubbed "a moral calculus for violence". It was originally published for $US120.00 but now sells second-hand for three or four times that on Amazon.

Have you read any books by Vollmann? What do you think of his work?

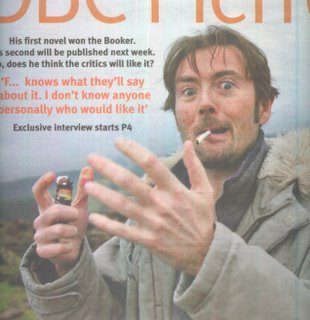

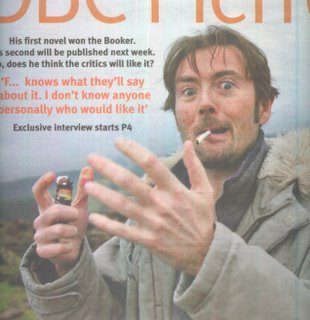

Sunday, 18 June 2006

This was handed in as an assignment for one of the units of study in my postgraduate award course. The mark my tutor awarded was a more than respectable 87. What do you think of it?

When A Clean Break Gets Dirty

DBC Pierre has traversed the highway from obscurity to literary success — and global notoriety. Where will this forty-something author go from here?

A radical faction in a religious sect had planned to turn a nuclear power station into an atomic bomb. Stung by the ensuing publicity, the sect disclaimed all its tenets. After the event, it must forge a new path.

This brief synopsis of Kenzaburo Oe’s 2003 novel, Somersault, could apply to writer DBC Pierre’s life since that year, as it has traced a similar trajectory but, as in a photographic negative, with the tones inverted.

The explosive device in Pierre’s case was Vernon God Little, his first novel — a rapid and inspiring romp through the preposterous and poignant backstreets of suburban U.S.A. — which propelled him into the stratosphere, securing the Man Booker Prize. In 38 years, only one other first novel has ever won the prize. Global sales of the novel, including translations into 43 languages, are healthy at around 1.5 million.

Like the sect, Pierre stood — and stands — outside the mainstream. Before the life-changing event no-one knew he even existed. But with the release to mixed reviews of his second novel, the startling Ludmila’s Broken English, he must start to forge a new path.

It’s apparently not enough that the novel is so different, in subject, tone and structure, from its predecessor. “Well, there aren’t many writers who’ve had such an extraordinary life, so I suppose it’s inevitable,” said his London agent, Clare Conville. “And I think, sort of, a backlash is inevitable, his success, you know, was so incredible.”

Pierre was born Peter Finlay in Adelaide, grew up in Mexico, and lived a wayward life in the U.S., Australia, the Caribbean, and England. He now works in a secluded corner of Ireland. Almost without exception, commentators have expressed mixed feelings about his chequered past, coloured as it is by inglorious undertakings.

Winning the Booker, among the most prestigious prizes in the literary world, seems to have exerted a quantum of pressure on the 43-year-old to conform to our view of what an award-winning author should be. It is true that he has survived many adventures, from illegal importing of cars to drug abuse, from obtaining money under false pretences to domiciling in Ireland for tax reasons. (A interviewer recently added this to his list of sins. But while this latest accusation is also no doubt true, it is relatively venal compared to the rest).

For critics to accept that a new writer deserves their applause, the difficult second novel must be unquestionably good. This is. But in Pierre’s case it must also be demonstrably virtuous. And this is anything but. Like DBC Pierre himself, the novel is ‘dirty but clean.’ It is a frazzled and imaginative hurly-burly filled with intimations of mortality and Shakespearian phrases that confound expectations.

“I haven’t seen any of them,” said Pierre philosophically when asked about the reviews during a talk to promote the book in The Rocks with Sydney Writer’s Festival doyenne Caro Llewellyn. “It doesn’t matter. Well, first of all, I just feel lucky to have a job, anyway. So I’m not that fussed, but if those reviews came out when I was still writing it, that would be problematic. But there’s a timeline — and it’s easy to forget — that once you deliver a book it walks on its own feet, and I’m just not responsible for it. There’s nothing you can absolutely do any more, you can’t go back in and shift anything… it’s all after the fact. … You know, I had to take risks and try and become a good writer, as best I could. And that’ll take a while.”

At his previous appearance, for the 2004 Festival, the Sydney Theatre was filled. This time attendance was limited by organisers, and about 100 antipodean fans entered the Belgian Beer Café from the bright autumn sunlight.

Did he think the world is harder for people who don’t fit the mould, asked Llewellyn: “I’m still trying to figure that one out,” he said. “I certainly don’t think that your loose cannons and your explosive people roaming outside the herd are any danger at all to society. In fact they’re probably the mixers that keep the rest of us in some sort of cohesiveness. But I’m still wondering what the relative benefits are of sticking with the pack and just having a nice life versus… not quite getting things together and staying outside the edge of it. And it’s interesting… we need both of them anyway, really. Especially, if you’re a bit of an outsider you need the herd to come and pick up the pieces when you hit the wall. And they probably need something to look at on TV every night.”

Having lost his footing on numerous occasions, Pierre speaks from experience, and his attempt to distance himself from those outside the mainstream is unconvincing. But he is genuinely determined to succeed. “He’s very firmly sure about what he wants to do and how he wants to do it,” said Conville.

Pierre’s ‘radical faction’ remain his drive, imagination, and sense of humour — the qualities that launched his career and now propel him past the obstacles set in his path. He seems determined to make the best of things. Living always in foreign countries, he has felt an outsider all his life and he admitted that this has touched his work: “Since writing I have found that that’s really helpful, actually. It’s good.”

I bought a copy of Ludmila’s Broken English as soon as it became available and enjoyed it immensely. It is quite sufficient to upset him that others didn’t, yet he appears resigned to completing any number of about-turns, fulfilling the role of enfant terrible of modern publishing, his new work both awaited and bemoaned. But only a month after the novel’s release it generates almost 40 pages of Google-search results.

That’s a solid endorsement, especially for an outsider, and indicative of better things to come. Having faced new challenges since the initial detonation of fame, it’s not beyond the pale of probability that Pierre will experience further somersaults in his life. After all, Oe had to wait 36 years for his Nobel Prize.

When A Clean Break Gets Dirty

DBC Pierre has traversed the highway from obscurity to literary success — and global notoriety. Where will this forty-something author go from here?

A radical faction in a religious sect had planned to turn a nuclear power station into an atomic bomb. Stung by the ensuing publicity, the sect disclaimed all its tenets. After the event, it must forge a new path.

This brief synopsis of Kenzaburo Oe’s 2003 novel, Somersault, could apply to writer DBC Pierre’s life since that year, as it has traced a similar trajectory but, as in a photographic negative, with the tones inverted.

The explosive device in Pierre’s case was Vernon God Little, his first novel — a rapid and inspiring romp through the preposterous and poignant backstreets of suburban U.S.A. — which propelled him into the stratosphere, securing the Man Booker Prize. In 38 years, only one other first novel has ever won the prize. Global sales of the novel, including translations into 43 languages, are healthy at around 1.5 million.

Like the sect, Pierre stood — and stands — outside the mainstream. Before the life-changing event no-one knew he even existed. But with the release to mixed reviews of his second novel, the startling Ludmila’s Broken English, he must start to forge a new path.

It’s apparently not enough that the novel is so different, in subject, tone and structure, from its predecessor. “Well, there aren’t many writers who’ve had such an extraordinary life, so I suppose it’s inevitable,” said his London agent, Clare Conville. “And I think, sort of, a backlash is inevitable, his success, you know, was so incredible.”

Pierre was born Peter Finlay in Adelaide, grew up in Mexico, and lived a wayward life in the U.S., Australia, the Caribbean, and England. He now works in a secluded corner of Ireland. Almost without exception, commentators have expressed mixed feelings about his chequered past, coloured as it is by inglorious undertakings.

Winning the Booker, among the most prestigious prizes in the literary world, seems to have exerted a quantum of pressure on the 43-year-old to conform to our view of what an award-winning author should be. It is true that he has survived many adventures, from illegal importing of cars to drug abuse, from obtaining money under false pretences to domiciling in Ireland for tax reasons. (A interviewer recently added this to his list of sins. But while this latest accusation is also no doubt true, it is relatively venal compared to the rest).

For critics to accept that a new writer deserves their applause, the difficult second novel must be unquestionably good. This is. But in Pierre’s case it must also be demonstrably virtuous. And this is anything but. Like DBC Pierre himself, the novel is ‘dirty but clean.’ It is a frazzled and imaginative hurly-burly filled with intimations of mortality and Shakespearian phrases that confound expectations.

“I haven’t seen any of them,” said Pierre philosophically when asked about the reviews during a talk to promote the book in The Rocks with Sydney Writer’s Festival doyenne Caro Llewellyn. “It doesn’t matter. Well, first of all, I just feel lucky to have a job, anyway. So I’m not that fussed, but if those reviews came out when I was still writing it, that would be problematic. But there’s a timeline — and it’s easy to forget — that once you deliver a book it walks on its own feet, and I’m just not responsible for it. There’s nothing you can absolutely do any more, you can’t go back in and shift anything… it’s all after the fact. … You know, I had to take risks and try and become a good writer, as best I could. And that’ll take a while.”

At his previous appearance, for the 2004 Festival, the Sydney Theatre was filled. This time attendance was limited by organisers, and about 100 antipodean fans entered the Belgian Beer Café from the bright autumn sunlight.

Did he think the world is harder for people who don’t fit the mould, asked Llewellyn: “I’m still trying to figure that one out,” he said. “I certainly don’t think that your loose cannons and your explosive people roaming outside the herd are any danger at all to society. In fact they’re probably the mixers that keep the rest of us in some sort of cohesiveness. But I’m still wondering what the relative benefits are of sticking with the pack and just having a nice life versus… not quite getting things together and staying outside the edge of it. And it’s interesting… we need both of them anyway, really. Especially, if you’re a bit of an outsider you need the herd to come and pick up the pieces when you hit the wall. And they probably need something to look at on TV every night.”

Having lost his footing on numerous occasions, Pierre speaks from experience, and his attempt to distance himself from those outside the mainstream is unconvincing. But he is genuinely determined to succeed. “He’s very firmly sure about what he wants to do and how he wants to do it,” said Conville.

Pierre’s ‘radical faction’ remain his drive, imagination, and sense of humour — the qualities that launched his career and now propel him past the obstacles set in his path. He seems determined to make the best of things. Living always in foreign countries, he has felt an outsider all his life and he admitted that this has touched his work: “Since writing I have found that that’s really helpful, actually. It’s good.”

I bought a copy of Ludmila’s Broken English as soon as it became available and enjoyed it immensely. It is quite sufficient to upset him that others didn’t, yet he appears resigned to completing any number of about-turns, fulfilling the role of enfant terrible of modern publishing, his new work both awaited and bemoaned. But only a month after the novel’s release it generates almost 40 pages of Google-search results.

That’s a solid endorsement, especially for an outsider, and indicative of better things to come. Having faced new challenges since the initial detonation of fame, it’s not beyond the pale of probability that Pierre will experience further somersaults in his life. After all, Oe had to wait 36 years for his Nobel Prize.

Monday, 12 June 2006

Today's a holiday, so after buying and reading the broadsheets this morning, I took a nap. Waking up just after 2:00 p.m., decided to buy some ethnic chow. Walked up Beamish Street to the Happy Chef Seafood and Noodle Restaurant, which is my usual resort when I don't feel like preparing my own food.

Sat in one of the new plastic chairs they've installed recently and got a menu. Ordered egg noodles with a side order of fried pork. They're pretty fast with the food up there and it arrived within five minutes. I polished it off pretty darn quick also. The 15-year-old waitress took my $8.50 and gave change.

I crossed the street to the two-dollar shop and picked up a face towel with which to wipe the inside of my windscreen in the mornings, when it's cold, and ambled into the Campsie Centre. Picked up a pack of smokes and checked out the newsagent's shelves, but the selection of magazines is not very encouraging. A downside to the multicultural nature of this suburb: they carry newspapers in Chinese, Vietnamese, Italian, Greek, Arabic, and what-not, but the mags are shocking. Not even The Economist, Quadrant or Vanity Fair, although they do have Quarterly Essay.

But further down Beamish Street in the other newsagent they had an old copy from March of The Economist, so I picked that up.

The sun is out today and the temperature around 17 or 18 degrees C, I reckon. Nice day for a stroll. But I quickly returned home.

Sat in one of the new plastic chairs they've installed recently and got a menu. Ordered egg noodles with a side order of fried pork. They're pretty fast with the food up there and it arrived within five minutes. I polished it off pretty darn quick also. The 15-year-old waitress took my $8.50 and gave change.

I crossed the street to the two-dollar shop and picked up a face towel with which to wipe the inside of my windscreen in the mornings, when it's cold, and ambled into the Campsie Centre. Picked up a pack of smokes and checked out the newsagent's shelves, but the selection of magazines is not very encouraging. A downside to the multicultural nature of this suburb: they carry newspapers in Chinese, Vietnamese, Italian, Greek, Arabic, and what-not, but the mags are shocking. Not even The Economist, Quadrant or Vanity Fair, although they do have Quarterly Essay.

But further down Beamish Street in the other newsagent they had an old copy from March of The Economist, so I picked that up.

The sun is out today and the temperature around 17 or 18 degrees C, I reckon. Nice day for a stroll. But I quickly returned home.

Saturday, 10 June 2006

Got a tip from be_zen8 in a comment to this blog that there's a sale on at Gleebooks this long weekend. So after showering I stopped off at Campsie shopping centre to do my weekend shopping. Then I headed off to see what they had on offer.

The first section of my journey mirrored the trajectory I traced last weekend. But instead of crossing Parramatta Road at Leichhardt, I turned right into it and followed it up to Sydney University, where I turned left into Ross Street. Then right into St John's Road, where I parked. Walked up to the old Gleebooks shop at No. 191 Glebe Point Road and discovered I'd gone to the wrong place. So I trekked down to the new shop at No. 49 and up the stairs on the left.

There are three tables with sale books. Many are non-fiction titles, with a fair collection of Palgrave editions on things like marketing and globalisation. Not that many novels, unfortunately. I spent $24.95 on four books. They are:

Watson's Dictionary of Weasel Words, Contemporary Clichés, Cant & Management Jargon, Don Watson (2004)

Tietam Brown: A Novel, Mick Foley (2003)

Kissing the Rod: An Anthology of Seventeenth-Century Women's Verse, with an introduction by Germaine Greer (1988)

Gregory's Canberra 2004 Street Directory

On the way back I stopped in at Cornstalk Bookshop to see what had happened to their shop in King Street, Newtown, which closed some months ago. "Everybody says that," said Resh, the girl at the computer to the left as you walk in, when I asked why it had shut. Why did they close? "Rent," she said. Apparently the building's owners kept putting up the rent until it became uneconomical. They had sales at 25%, 50% then 75% of the sticker price and finally a bloke with a bookshop across the road bought the rest.

It's sad, to see a good outlet shut down. Especially one like Cornstalk which had been there so long. The awning on King Street still says Cornstalk Bookshop, but the shop itself is gone, never to return. Paul Feain, who runs Cornstalk, keeps mostly Australiana at his Glebe Point Road store, so the general second-hand stuff has just disappeared. I wonder if he'll open another outlet in the future.

My return journey exactly mirrored my outward trajectory. It started to rain. I was flicking the wipers on and off from Crystal Street, and at Canterbury Road switched them to intermediate mode. Hopefully it'll keep raining for a few more days. We need it.

The first section of my journey mirrored the trajectory I traced last weekend. But instead of crossing Parramatta Road at Leichhardt, I turned right into it and followed it up to Sydney University, where I turned left into Ross Street. Then right into St John's Road, where I parked. Walked up to the old Gleebooks shop at No. 191 Glebe Point Road and discovered I'd gone to the wrong place. So I trekked down to the new shop at No. 49 and up the stairs on the left.

There are three tables with sale books. Many are non-fiction titles, with a fair collection of Palgrave editions on things like marketing and globalisation. Not that many novels, unfortunately. I spent $24.95 on four books. They are:

Watson's Dictionary of Weasel Words, Contemporary Clichés, Cant & Management Jargon, Don Watson (2004)

Tietam Brown: A Novel, Mick Foley (2003)

Kissing the Rod: An Anthology of Seventeenth-Century Women's Verse, with an introduction by Germaine Greer (1988)

Gregory's Canberra 2004 Street Directory

On the way back I stopped in at Cornstalk Bookshop to see what had happened to their shop in King Street, Newtown, which closed some months ago. "Everybody says that," said Resh, the girl at the computer to the left as you walk in, when I asked why it had shut. Why did they close? "Rent," she said. Apparently the building's owners kept putting up the rent until it became uneconomical. They had sales at 25%, 50% then 75% of the sticker price and finally a bloke with a bookshop across the road bought the rest.

It's sad, to see a good outlet shut down. Especially one like Cornstalk which had been there so long. The awning on King Street still says Cornstalk Bookshop, but the shop itself is gone, never to return. Paul Feain, who runs Cornstalk, keeps mostly Australiana at his Glebe Point Road store, so the general second-hand stuff has just disappeared. I wonder if he'll open another outlet in the future.

My return journey exactly mirrored my outward trajectory. It started to rain. I was flicking the wipers on and off from Crystal Street, and at Canterbury Road switched them to intermediate mode. Hopefully it'll keep raining for a few more days. We need it.

This post is for careful householders, especially those in New South Wales.

Sydney is on a consumption reduction drive. 'WaterFix' is a good deal for householders. Spend $22.00 and they install a new shower head (and arm), check for leaks, replace all washers in your home, and install water-efficient aerators on your taps.

Keith is a contractor with Sydney Water and has been a plumber since the age of 15. He services 10 homes every day. There's plenty of work for contractors, and since leaving full-time employment with Sydney Water a decade ago, he's been fully employed. He arrived on time — just as I got home yesterday — and worked quickly to finish the job within half an hour.

My new shower head — haven't even used it yet — is called a 'Bermuda Flexispray'. When you twist the bottom of the head to the left the flow diverts and out shoots a thumping stream of water. Twist it back and the flow reverts to a gentle shower.

The company is making it easy for home owners to upgrade their water delivery systems. They make appointments after hours and on weekends. Keith says that if he wanted to work all weekend, there's plenty of work. He covers a different area every day. Yesterday he was in the Sutherland area and tomorrow it'll be somewhere else. Each home he services looks to save 21,000 litres of water annually.