There’s an ABC sports newsreader named Catherine Murphy who has a Scots accent. What is she doing here, in Australia, telling us about ALF and soccer? And how did a Scot come to have an Irish name? And haven’t we already got Katharine Murphy (the political correspondent for the Guardian)? Did we really need another one?

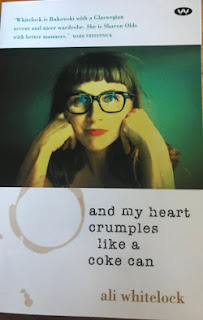

There’s an ABC sports newsreader named Catherine Murphy who has a Scots accent. What is she doing here, in Australia, telling us about ALF and soccer? And how did a Scot come to have an Irish name? And haven’t we already got Katharine Murphy (the political correspondent for the Guardian)? Did we really need another one?Ali Whitelock comes along with her stream-of-consciousness narratives like some sort of improved version of Molly Bloom made real in the world, complete with a laptop, a dog and a house by the sea. In his foreword to the book, poet Mark Tredinnick works very hard to get us to like her, comparing her favourably to Charles Bukowski, the American poet who found popularity in the 80s and who still seems to have a readership despite some unpleasant rumours. I’m not sure the analogy quite fits the case, although Whitelock strikes me as being as observant of society’s foibles as Chuck was while he was alive. Her satire and deadpan delivery frequently made me smile.

Some of the poems, furthermore, are quite perfect, such as ‘o fair and gentle leek’, ‘please do not pee in the sink’, and ‘the shit we are in’. In these, the story rumbles on comfortably like any old stray set of diurnal thoughts until it reaches the end, and then stops just at the right moment. Not all of the poems have this degree of precision and focus, but all share a down-home sagacity of a kind that we certainly need more in the public sphere. Whitelock might be a marooned Scot who has touchingly made a home for her mortality in the ungainly sprawl of Australia’s feckless suburbia, but she is not without a healthy strain of snark that she deploys to noticeable effect when occasion demands.

This reliance on the day-to-day to help create meaning does however kerb the poet’s ability to isolate larger truths for the benefit of the reader. There is a stubborn domesticity here that works very well to furnish trenchant material for social commentary, but that yet means that the poems for the main part are tethered to the mundane. They are hymns to the everyday that will suit any denomination or creed, but more rarefied truths are infrequent visitors to the lovely sallies contained in this slim volume. Even the book’s title serves to gently link the spirit tightly to the secular realm, but you wonder if Whitelock might one day reach past the drink container, the commercial forces that support its existence, and the social relations that are influenced by them, to ponder things lying beyond the margins of the world as it appears in newspaper headlines. I wanted to say more in this vein, but I had second thoughts. It’s not that I want to pull my punches, but I want to wait for more evidence before making bald statements.

To finish up, I almost whooped when she flagged the Robbie Burns statue that sits optimistically on its granite plinth near the Art Gallery of New South Wales, between an Angel’s trumpet to the south and the Police Service Wall of Remembrance to the north. The Latin name for the tree is Brugmansia. It’s a poisonous introduced species related to the tomato and the potato. On sunny weekdays, joggers who work in offices in the towers situated just past the western edge of the Domain run past the statue of Scotland’s favourite son, complete with its plough, as they take time out from their busy schedules to get some air into their lungs and to work the kinks out of tired muscles. But few people notice this bit of civic art, a relique of a simpler time, the age of Henry Lawson and the White Australia Policy, although many certainly wish that we could turn the clock back and make the country conform to its values again. It would be nice if we could just keep the good bits, though, without the nationalistic exceptionalism and all the other disreputable baggage that went along with it.

Catherine Murphy has an Irish accent - she's Irish from County Cavan.

ReplyDelete