Lyall Munro’s speech at Myall Creek Memorial Rock followed an emotional Fred Chaney’s. The former federal minister for aboriginal affairs (1978 - 1980) compared remembering June 1838 to ANZAC Day.

Chaney does ANZAC Day marches with his grandfather’s unit medals - from AIF fighting in Europe - on his chest.

He has done for decades. “Walking down this path I had the same sense as on ANZAC Day.”

Myall Creek was a totally unnecessary destruction. “The sense of grief is no different.”

Munro welcomed assembled participants - numbering 430 this year, a good 200 more than usual since remembrance ceremonies began:

“I know you’re a sincere people, otherwise you wouldn’t be here.”

“The Europeans outgunned us,” he admitted. Munro and Chaney go back a way. Chaney was once deputy chair of the Australian Native Title Tribunal.

“What I said 50 years ago seems like yesterday,” said Munro. “Fifty years is quick.”

“Your critics are not your enemies,” said Chaney, now co-chair of Reconciliation Australia. For years Munro gave him "powerful advice and trenchant criticism". He thanked Munro for letting their friendship flourish despite "many mistakes".

Munro was the driver behind events on 7 June 2008. This became clear when, near the end of proceedings, John Brown, a man involved since 2000, tried to schedule a meeting.

Munro walked quietly up to Brown - at the mic - and whispered to him. “It seems we’re not having a committee meeting,” announced a flustered Brown. But Munro kept to the rear except for a brief turn at the mic at the memorial Rock.

Chaney told us, as he stood in front of it, that all government departments were preparing ‘reconciliation action plans’ to work out how to fit in a post-Sorry world.

The government was committed to recognising and protecting indigenous heritage, said Peter Garrett.

He handed a National Heritage plaque to an elder in front of guests seated outside the Myall Creek Country Womens’ Association (CWA) hall.

The corrugated iron building is situated ten minutes south of the tiny Northern Tablelands town of Delungra (pop 330), just west of Inverell on the Gwydir Highway.

There are now 79 places on the National Heritage List.

Myall Creek was important for all Australians, Garrett said. “It was the first and last time the colonial administration intervened to ensure British law applied equally” to blacks and whites.

Paul Lynch, NSW minister for aboriginal affairs and history buff, repeated the same message later in the day. He noted that absentee landlord Henry Dangar was also instrumental in the 1890s' shearers’ strikes, events leading to establishing the Australian Labor Party (ALP).

The Memorial Walk started in bright sunlight up on the hilltop with a delicate composition by Neil Murray sung by the group A Third Below.

Then the fragrant smoke of gum tree leaves.

Ochre and ashes, daubed on the face or forehead, signify the assembled - citizens, children, school kids, reporters, police, politicians, musicians, photographers, and descendants of those alive 170 years ago - pay respects. The order of service notes there is “a long Jewish/Christian tradition of putting on ashes as a sign of sorrow and grieving”.

At each of the eight stations school children - stately and happy in green or blue local uniforms - gave a brief version of events of June 1838. Similar words are inscribed on plaques mounted on rocks on the way.

They have been coming for years, and the support of people like them - “All reconciliation is local” said a tearful Chaney - had moved the Myall Creek Memorial Committee to propose the successful heritage listing.

This is very much the local community's ceremony, not just the aborigines’. Despite Chaney's words, grown-up children will be making the kind of concessions and decisions that will follow 7 June 2008.

Already Glenn Milne in The Sunday Telegraph (‘A Memorial controversy’ 8 June 2008) writes that the RSL disapproves of a suggestion - from Labor's Peter Conway - to establish an ‘Aboriginal Wars’ memorial on Canberra's ANZAC Avenue.

For this reason the Barwon LAC uniform of Chris Styles stood out. He shared the patch of dry grass scattered with bark and sticks off shade eucalypts with hundreds of aboriginal and non-aboriginal citizens.

Silence fell until the bullroarer began to hum. Chaney, Munro and others spoke in the silence of the crackling, dry bush. Children played with gravel strewn at their parents' feet before the Rock.

Many participants signed a visitors' book placed under a nearby gum tree.

John Heath, a part-aboriginal from Port Macquarie, where Henry Dangar lived, has studied Myall Creek for years. Walk with him for 20 minutes - as long as it takes to reach the CWA hall - and you learn a lot of pre-WWI history.

We agreed that convicts - seven of whom hung for murder in 1838 - would have been loath to disagree with an overseer.

Chaney had mentioned "one man of principle" - George Anderson. Anderson worked at Myall Creek Station and alerted the Muswellbrook magistrate after witnessing stockmen lead away a group of trussed aborigines.

But the status of ticket-of-leavers and convicts made them susceptible to violence.

Communication in this kind of environment - unmediated and freely shared - gets you details often missing in the daily media.

Dympna and Diana from Armidale, and Russell from a closer town, talked freely with people they’d never met. Author Peter Stewart was on hand to sign copies of his book, Devils At Dusk (see Friday‘s post).

Organisers didn’t expect so many. Graeme Cordiner, of Sydney Friends of Myall Creek, said at 10.05: “this is what we usually get”. Half an hour later it had doubled.

The Gomeroi Dance Group Company impersonated a family of ‘banda’ ('kangaroo' in Gamilaroy language). Sleepy to start with, banda stir, raise their ears, and rise to look around.

Prizes were awarded for artworks by local kids. Madison Eastcott from Bingara Central School accepted first prize for category two. The Tingha Singers performed a children’s song in their language.

In the photos you can see the local Gamilaroy boys lazing around just like regular kangaroos before starting up, ears twitching, to survey the environment. “It takes a bit of acting,” they said. “We’re all actors in case you're a movie producer.” They're keen to succeed.

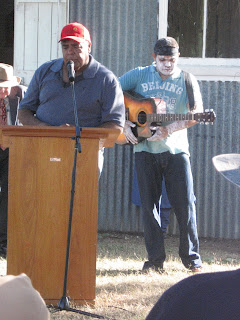

Roger Knox, accompanied by one talented youth, sang a song.

I am what I am

I am aborigine

I am like a river

Pollute and abuse me

And I will die

Taking only what I must

I am what I hunt.

Chaney does ANZAC Day marches with his grandfather’s unit medals - from AIF fighting in Europe - on his chest.

He has done for decades. “Walking down this path I had the same sense as on ANZAC Day.”

Myall Creek was a totally unnecessary destruction. “The sense of grief is no different.”

Munro welcomed assembled participants - numbering 430 this year, a good 200 more than usual since remembrance ceremonies began:

“I know you’re a sincere people, otherwise you wouldn’t be here.”

“The Europeans outgunned us,” he admitted. Munro and Chaney go back a way. Chaney was once deputy chair of the Australian Native Title Tribunal.

“What I said 50 years ago seems like yesterday,” said Munro. “Fifty years is quick.”

“Your critics are not your enemies,” said Chaney, now co-chair of Reconciliation Australia. For years Munro gave him "powerful advice and trenchant criticism". He thanked Munro for letting their friendship flourish despite "many mistakes".

Munro was the driver behind events on 7 June 2008. This became clear when, near the end of proceedings, John Brown, a man involved since 2000, tried to schedule a meeting.

Munro walked quietly up to Brown - at the mic - and whispered to him. “It seems we’re not having a committee meeting,” announced a flustered Brown. But Munro kept to the rear except for a brief turn at the mic at the memorial Rock.

Chaney told us, as he stood in front of it, that all government departments were preparing ‘reconciliation action plans’ to work out how to fit in a post-Sorry world.

The government was committed to recognising and protecting indigenous heritage, said Peter Garrett.

He handed a National Heritage plaque to an elder in front of guests seated outside the Myall Creek Country Womens’ Association (CWA) hall.

The corrugated iron building is situated ten minutes south of the tiny Northern Tablelands town of Delungra (pop 330), just west of Inverell on the Gwydir Highway.

There are now 79 places on the National Heritage List.

Myall Creek was important for all Australians, Garrett said. “It was the first and last time the colonial administration intervened to ensure British law applied equally” to blacks and whites.

Paul Lynch, NSW minister for aboriginal affairs and history buff, repeated the same message later in the day. He noted that absentee landlord Henry Dangar was also instrumental in the 1890s' shearers’ strikes, events leading to establishing the Australian Labor Party (ALP).

The Memorial Walk started in bright sunlight up on the hilltop with a delicate composition by Neil Murray sung by the group A Third Below.

Then the fragrant smoke of gum tree leaves.

Ochre and ashes, daubed on the face or forehead, signify the assembled - citizens, children, school kids, reporters, police, politicians, musicians, photographers, and descendants of those alive 170 years ago - pay respects. The order of service notes there is “a long Jewish/Christian tradition of putting on ashes as a sign of sorrow and grieving”.

At each of the eight stations school children - stately and happy in green or blue local uniforms - gave a brief version of events of June 1838. Similar words are inscribed on plaques mounted on rocks on the way.

They have been coming for years, and the support of people like them - “All reconciliation is local” said a tearful Chaney - had moved the Myall Creek Memorial Committee to propose the successful heritage listing.

This is very much the local community's ceremony, not just the aborigines’. Despite Chaney's words, grown-up children will be making the kind of concessions and decisions that will follow 7 June 2008.

Already Glenn Milne in The Sunday Telegraph (‘A Memorial controversy’ 8 June 2008) writes that the RSL disapproves of a suggestion - from Labor's Peter Conway - to establish an ‘Aboriginal Wars’ memorial on Canberra's ANZAC Avenue.

For this reason the Barwon LAC uniform of Chris Styles stood out. He shared the patch of dry grass scattered with bark and sticks off shade eucalypts with hundreds of aboriginal and non-aboriginal citizens.

Silence fell until the bullroarer began to hum. Chaney, Munro and others spoke in the silence of the crackling, dry bush. Children played with gravel strewn at their parents' feet before the Rock.

Many participants signed a visitors' book placed under a nearby gum tree.

John Heath, a part-aboriginal from Port Macquarie, where Henry Dangar lived, has studied Myall Creek for years. Walk with him for 20 minutes - as long as it takes to reach the CWA hall - and you learn a lot of pre-WWI history.

We agreed that convicts - seven of whom hung for murder in 1838 - would have been loath to disagree with an overseer.

Chaney had mentioned "one man of principle" - George Anderson. Anderson worked at Myall Creek Station and alerted the Muswellbrook magistrate after witnessing stockmen lead away a group of trussed aborigines.

But the status of ticket-of-leavers and convicts made them susceptible to violence.

Communication in this kind of environment - unmediated and freely shared - gets you details often missing in the daily media.

Dympna and Diana from Armidale, and Russell from a closer town, talked freely with people they’d never met. Author Peter Stewart was on hand to sign copies of his book, Devils At Dusk (see Friday‘s post).

Organisers didn’t expect so many. Graeme Cordiner, of Sydney Friends of Myall Creek, said at 10.05: “this is what we usually get”. Half an hour later it had doubled.

The Gomeroi Dance Group Company impersonated a family of ‘banda’ ('kangaroo' in Gamilaroy language). Sleepy to start with, banda stir, raise their ears, and rise to look around.

Prizes were awarded for artworks by local kids. Madison Eastcott from Bingara Central School accepted first prize for category two. The Tingha Singers performed a children’s song in their language.

In the photos you can see the local Gamilaroy boys lazing around just like regular kangaroos before starting up, ears twitching, to survey the environment. “It takes a bit of acting,” they said. “We’re all actors in case you're a movie producer.” They're keen to succeed.

Roger Knox, accompanied by one talented youth, sang a song.

I am what I am

I am aborigine

I am like a river

Pollute and abuse me

And I will die

Taking only what I must

I am what I hunt.

No comments:

Post a Comment