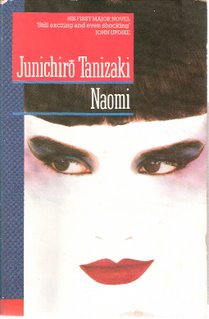

Review: Naomi, Junichiro Tanizaki (1986)

Review: Naomi, Junichiro Tanizaki (1986)After finishing this wonderful book, I unwrapped The Sydney Morning Herald and began reading. It wasn't long before I found an echo. On page 2 of the newspaper, I came across a story about The Big Day Out, which is an annual rock concert here that took place this year the day before Australia Day (which is today, in case you're wondering).

The concert has been in the news a lot over the past few days because organisers had initially banned Australian flags, in order to lessen the danger of anti-social events. (You might recall that Australian flags were prominent in last year's Cronulla riots, when thousands of Anglo Australians rampaged through the suburb in retaliation to violence perpetrated by men of Lebanese extraction.)

What caught my attention was this:

Seventeen-year-old Dana Burgess, from Richmond, with a newly purchased flag over her shoulders, said she had not worn a flag before but "as soon as they said they would be banned I started thinking about ways to smuggle them in".

Tanizaki caused shivers on my arms when I read his novel. It is a strange story, a tale of metamorphosis, rebellion, change and fear. It is a love story. It is a coming-of-age story. It is a Pygmalion story.

It is all these things and more. In the 'more' category is the sensation that you are reading about a whole generation of Japanese moving into the modern world. The changes that arrive via Naomi's willful personality rock the foundations of society, it seems.

Joji initially meets Naomi in the Diamond Cafe, where she is working as a serving girl. She is fifteen. He takes an avuncular interest in her. Joji is a traditional man from a rural family who works as an engineer in Tokyo, earning (this is comical) 150 yen a month. He is independent and wishes to take Naomi in. He wishes to mould her to fit an ideal form.

He pays for English lessons and music lessons. They rent an atelier (a split-level house in Omori, a suburb of central Tokyo). They take up dancing lessons together. This is where things start to come unstuck. As Naomi begins to savour her independence, she changes, mutates, morphs and metamorphoses. Joji stumbles in his attempts to keep up: she is not becoming the woman he envisaged.

She makes friends with various men. She and Joji row, he kicks her out, he pines for her, she inches back into his life (being careful to establish her own conditions for cohabitation). Although they are legally married, Joji accepts this weird form of 'friendship' because, simply, he cannot live without her.

Naomi knows this and plays it for all it's worth, coming onto him and repulsing him by turns. From an awkward teenager, she has become a commanding young woman. The five years that account for the bulk of the narrative seem like an eternity. On page 165, the following exchange takes place which sums up, for me, much about the allure of the book:

'You don't mind, do you, if I go upstairs for my things?' the apparition said. Judging from the voice, it was Naomi after all, not a ghost.

'All right... I don't mind, but...' Clearly I was flustered. I added shrilly, 'How did you open the door?'

'How? With a key.'

'But you left your key here.'

'Oh, I have lots of keys, not just one.' A smile came suddenly to her red lips, and she gave me a look that was both coquettish and derisive. 'I didn't tell you before, but I made lots of keys, so it doesn't bother me if you take one of them.'

So, it's this kind of novel. Small details expand in your mind, adopting larger significance. The pace is just right: intimate and painstaking in one place, brisk and leaping in another.

I will be reading more books by this very talented author, to be sure.

Note that the translation date shown at the beginning of this review relates to a later edition of the book than the original one. This translation, by Anthony Chambers, relates to the Chuo Koran-Sha, Inc. edition of Chijin No Ai, published in 1985. I do not know when the original translation appeared. Considering the fact that there is no proper Tanizaki biography available in English, it is possible that this translation was the first. The book was originally published in 1924 (sometimes it's 1923). Chijin No Ai translates concisely as 'A Fool's Love'.

No comments:

Post a Comment