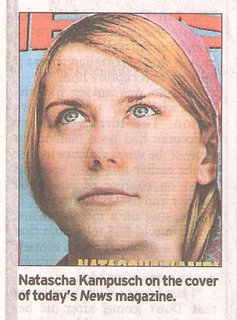

Natascha Kampusch doesn't want a new book, written by Allan Hall and Michael Leidig and published in the United Kingdom on 30 November by Hodder & Stoughton, to be out there. "She ... has threatened to sue anyone who printed untruths about her that infringed her 'personality rights'," according to The New Zealand Herald. A press release emerged from the publishing company:

Natascha Kampusch doesn't want a new book, written by Allan Hall and Michael Leidig and published in the United Kingdom on 30 November by Hodder & Stoughton, to be out there. "She ... has threatened to sue anyone who printed untruths about her that infringed her 'personality rights'," according to The New Zealand Herald. A press release emerged from the publishing company:"Hodder & Stoughton publishers have taken steps to ensure that the book [Girl in the Cellar: The Natascha Kampusch Story] complies with appropriate legal requirements," it said. "They do not intend to market the book in Europe outside the UK."

In Sydney, The Australian has not touched the story since it broke, as far as I can ascertain. But The Sydney Morning Herald published stories on 28, 29 and 31 August, on the weekend of 2-3 September and on 7 September and 12 October. There was also a longer feature that I neglected to clip.

One of the stories I read, on 28 August, was entitled ‘Freed girl remains captive to lost childhood’. In this globally-televised drama, Kampusch, an Austrian teenager, having been abducted at the age of ten by a communications technician named Wolfgang Priklopil, escapes from his house after eight years in captivity. Her mother, Brigitta Sirny, and her father, Ludwig Koch, remain concerned about her, as you’d expect after so many anguished years of separation. “Investigators said Ms Kampusch — who had a brief and emotional reunion with her family — had not expressed a desire to see them again.” “‘Everyone wants to ask intimate questions, [but] they don’t concern anyone. I feel good where I’m at now,’” said Natascha resolutely. The authorities worry about Stockholm syndrome.

Neither the agent responsible for rights to publish the book nor The Times, which published extracts from the book on its Web site, returned calls placed by the Reuters journalist who wrote the story.

It wasn’t at first clear just why her story affected me so much. Possibly because Natasha had become so completely estranged from her biological parents, and extremely attached to her abductor. “The beatings that a young miniaturist receives from his master bind him to his master with a profound respect until the day he dies.” — My Name is Red, Orhan Pamuk.

No comments:

Post a Comment