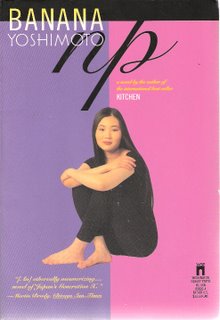

Review: N.P., Banana Yoshimoto (1995)

Review: N.P., Banana Yoshimoto (1995)In this deliriously sexy little novel, we find a whole world of delights that fulfill and satisfy our craving for fictional indulgence. Summer in Tokyo: the heat, the sweat, the nights drinking tea on the pavement, the trucks rumbling past on the busy road.

But we also find ourselves mixed up with a curiously intimate bunch of young people who are struggling to find themselves in the world. Kazami, the narrator, had seen Otohiko and Saki once before, many years earlier, when she was a high-school student and in love with Shuji. It was at a special event in one of those ritzy central-Tokyo function rooms. The brother and sister were standing together smiling, laughing. Kazami has never forgotten, and one day, years later, when she is on lunch break from her work at the university, she spies Saki in the street and introduces herself.

She discovers that Otohiko is in love with his half-sister, Sui, who had been the lover of her own father back in Boston, where the siblings grew up. Sarao Takase, the writer who made love to his own daughter, wrote a collection of ninety-seven stories, N.P., and the young people are wondering about the ninety eighth, which Shuji was translating into Japanese when he committed suicide. Otohiko and Sui believe this story is cursed.

But the muddle of the plot is the least wonderful thing about this novel. More important is the directness of Japanese peoples' interactions, the clashes and revelations that emerge, especially among a group of young people, like this, who are brought together by the strange facts surrounding Takase's work and life. They have inherited a lot of baggage, and are eager to find a way to deposit it somewhere. We worry that Kazami will be hurt by them. Strangeness pervades the novel like weeds in an untended garden.

Kazami, for her part, is a confident young woman. But she has her own demons. Her mother and father separated when she was a girl, and now he drinks and she continues to lecture her. She can't see herself living with either. She also has thoughts about Shuji, dead for many years, but still present: Sui had had an affair with him.

When you've fallen in love, broken up, lost a loved one, and start getting older, everything seems the same. I couldn't tell what was good and what was bad, what was better and what was worse. I simply didn't want to have any more bad memories. I wished that time would stop, and summer would never come to an end. I felt very vulnerable.

Little nuggets and jewels of wisdom like this pepper the narrative. Here's Sui:

"You know, I never have really had any friends. There were a lot of girls who I hung out with, but never anyone who I could talk with like this. I could talk with Otohiko, but he's the only other one."

"He's the man," I said. "Maybe that's why you were the perfect pair. You could complain, and talk about your doubts and still keep on going."

That's how most couples made a go of it anyway.

In a gap in the conversation that Kazami and Otohiko are having, Kazami contemplates her own mortality:

It started raining. I could hear the faint, dark sound through the open window. The melancholy that accompanies the night swept in and filled the room. It coldly watches those of us who dwell in our bodies as we struggle through the day. The shadow of death. The feeling of powerlessness that sneaks up on you when you're not watching; the desolation that will swallow you up if you let down your guard.

The erotic tinge, the bright, insistent sparkle of the prose, the strangeness of foreign-raised young Japanese people, and the heavy mystery surrounding those stories, combine in this short, thrilling little book to provide a terrific reading experience.

No comments:

Post a Comment