Review: Breakfast at Tiffany's, Truman Capote (1958)

Review: Breakfast at Tiffany's, Truman Capote (1958)Set in 1943 during World War II the eponymous novella is a fast-paced, episodic ramble with a highly entertaining young woman at its heart. Resembling Sophie's Choice, it tells the story of a young writer in a tenement in New York who becomes acquainted with an older woman, who has not only a clouded past but a propensity for flouting convention.

Unconventional as she is, Holly Golightly is refreshingly frank and stubbornly loyal. Fred, the writer, seems to become part of her life from the time he lets her in at two o'clock in the morning with the front-door buzzer: she has forgotten or lost her front-door key. It's not clear how she earns her living, but she does have an arrangement to visit Sally Tomato in Sing Sing prision in Ossining once a week and afterward relay a message to his friend Father O'Shaunessey. This liaison will come back to bite her later on. As it is in Norman Mailer's novel The Deer Park, from the same period, much of the dialog is opaque to us now, and attitudes to sex are so quaint as to seem almost Victorian. The realities are there, but set in code, a code the key to which which we have now lost.

The volume also contains three of Capote's short stories, one of which, A Diamond Guitar, contains the following:

Except that they did not combine their bodies or think to do so, though such things were not unknown at the farm, they were as lovers.

'They' in this quote are a pair of convicts, 'the farm' being a labour camp in the woods somewhere in the United States, a place where the winters are cold and the forests tall. Capote's frankness in this instance is compromised by his ass-backward way of talking about prison sex. These days we are far more open and deliberate about 'such things'.

Similarly, in Breakfast at Tiffany's, which is quite a racy story, the way that sex is discussed is encoded to prevent scandal. What Holly does for a living is not clear, but has something to do with restrooms and fifty dollars and men. No doubt people in those days would have understood the code, but since the swinging sixties we are oblivious to it.

The novella, Breakfast at Tiffany's is a masterpiece.

I read this book earlier this year and very much enjoyed it.

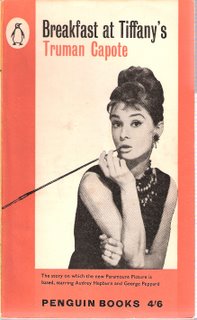

ReplyDeleteI ****love**** the cover of your edition, so funky and retro! ;)

This volume is an original first edition Penguin paperback, published in 1961, so it's authentically retro!

ReplyDeleteI picked it up at a book sale for a dollar.

I don't think we've lost the codes. I mean, just as you're saying we've lost them you actually decipher them quite well. I always thought Holly was someone men paid to have a date with, but not have sex with. The narrator visits her in her flat at all times of the day and night & there's never a bloke there is there? I think the money for the ladies rest rooms relates to having to tip a person who would hand you a towel or run the basin full of water for you (I saw this in New York only a few years ago - the people are always black). Wives or girlfriends would ask their husband for the money, and I guess that if he was generous he'd give more than was necessary, and she'd pocket the change. Obviously a time when women didn't have their own incomes. Horrible really, perhaps more demoralising than just straightforward cash-for-sex.

ReplyDeleteWell I didn't get it. And later in the book she's written up in the newspaper as some sort of socialite. The messages got crossed with me.

ReplyDeleteThose practices perhaps are still relevant but if you're paid to have a date with someone then why are the newspapers puffing her up into some sort of glamour queen?

Its quite a common link. Prostitutes have always had an element of glamour, and the higher-class they are the more glamorous they become. The ones at the top of the ladder sell company, not sex, and are definitely socialites - today as much as anytime. See page 22 of last weekend's SMH - "A man for all seasons, for every kind of woman" - for a description of blokes here in Sydney who bear many resemblances to Holly Golightly, or at least to her profession as "paid socialite".

ReplyDeleteJust found it online - see

http://www.smh.com.au/news/opinion/dress-codes-wore-crimes/2006/10/13/1160246325234.html?page=2