This is the first in a new series of posts that looks at works in my collection. I’ll take questions from an old school friend (though we haven’t met for four decades). Roger lives in the north of the state and I live in Sydney but we’re both passionate about art. The title of the series is due to how artworks are hung on walls, and also due to how each post should take about five minutes to read. Roger asks five questions, each of which I answer below.

Do you find the naive style of painting for ‘Bondi’ to be similar to Aboriginal art in the flat treatment of surfaces, sort of tactile / finger-painting in parts, and almost map-like aerial view?

Opposite ‘Bondi’ on another wall is an Aboriginal work (a print), so the question is especially relevant in the context of my house though I personally never thought of this type of influence. But since you raise it as a question it seems pertinent. Now that I think about it the way that Tuinstra has lofted the point of view to sit directly above the beach and the foreshore so that it looks like his use of perspective could have drawn inspiration from First Nations people’s unique ideas about figuration and representation of the natural world.

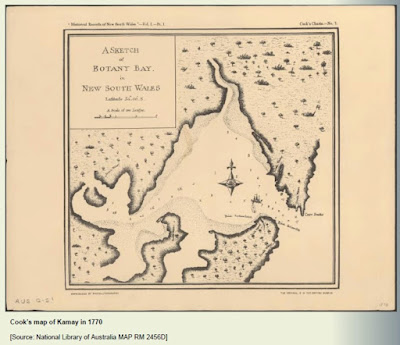

I didn’t come to grasp the relevance of their ideas until relatively recently, it must’ve been about twenty years ago. I don’t know why I was in the dark for so long, but I’d just never thought about Aboriginal art with that part of my mind. Once I grasped what was going on – how they elevate the viewpoint to sit in the air above the landscape – it all made sense in that Australia, being a continent, is so large and that in order to successfully get around you have to image the world as though it were printed on a map.

Interestingly, next to ‘Bondi' (bottom right) is a Sydney Morning Herald insert I had framed some years before I bought Tuinstra’s work. This is a satellite photograph showing Sydney from space. It is in the distinctively green-and-black colour scheme of all such photos, and demonstrates the size of the metropolis. You can see the M2 and M7 easements before the roads were actually completed.

I’m also seeing a possible influence of Brett Whiteley’s early NSW landscapes that he did in a simplified, abstracted fashion. Also David Hockney bells are ringing….you?

Tuinstra is American so it’s more likely that Hockney is an influence, though Tuinstra was living in Australia at the time ‘Bondi’ was made so he definitely would’ve come across Whiteley.

There is such a range of styles available nowadays for painters to borrow from that pretty much anything goes and I am encouraged by the feelings painters must have when they think about starting something new as part of their practice.

When I was young I remember picking a book on Pop Art as a school prize. I distinctly remember going to a bookshop in the CBD and feeling so happy when I came across it. Sadly the book isn’t in my collection anymore. (Many of the books I had as a boy are now dispersed although I still have a number that my cousin Douglas took and which his father, my uncle Geoff, brought up to Queensland to store when I was living in Japan.) What I mean to say is that it used to be that certain styles were prominent in various segments of time, but this singular focus no longer holds. Artists have a whole gamut of styles from which to pick influences which they can combine in new ways to make curious things. If you’re a painter working in Australia in 2021 or even if you were doing so in 2008 the possibilities are virtually endless. This must in a way be liberating as you would be able to explore different avenues in order to find the one that expresses your personality and the ideas that you think are important. But it also must be a tad frightening since, given enough openings, choosing one door could seem perilous.

Whiteley (1939-1992) and Hockney (b. 1937) are from the same generation of my parents. Whiteley sadly died from his addictions but Hockney is still going strong and his later works – I think he’s living back in England now – are just as striking as the ones you mention (the swimming pool pictures) but are quite different in concept. He has made a big impression on generations of artists, especially painters, and I think that your thoughts on ‘Bondi’ are on the nail in this respect. It’s arguable whether Aboriginal art was an influence on either Hockney or Whiteley. The former probably never came across it in his formative years and the latter, to me, seems to be influenced more by Asian art, especially Chinese brush painting.

Interesting viewing the pic in segments on the phone, it looks like a series of pictures on a coastal theme which can be viewed in different combinations. By breaking up the picture frame you are putting your own perspective of the picture, through the filter of an electronic medium and re-contextualising it. The picture has evolved - intentional?

The reason I sent you the detailed views of the painting was so that you could get an idea of the brushstrokes used to make it. I sent four different clips as attachments to one email, each displaying a small section of the painting, but this wasn’t done in order to make something different of my own. Here are a couple of the details I sent.

In the above photo you can see the impasto effect of the paint used for the beach. I think Tunistra originally had the beach in yellow but then changed it to green in order to complete the composition more effectively. The paint used for the beach is thicker than the paint used for other parts of the painting.

The above photo shows another small part of ‘Bondi’. Though my segmentalising was done for the sake of convenience it’s plausible to imagine someone making a new artwork out of segments of another person’s painting. You could snap some photos of a painting like ‘Bondi’, print them out on archival paper, and frame them, giving the resulting assemblage a distinct title.

Do you think nostalgia for a former home location may have altered your appreciation of the painting. I wonder how much is the enjoyment of memories and how much is pure aesthetic appeal?

Definitely Bondi has memories for me but it was, I think, the last one available in the show at Gallery 41, which was in Woolloomooloo. I used to live in Bondi, having bought an apartment there in 1988 before I moved to Japan to live. Also, this painting came direct from the framers to my new apartment in Maroochydore where I lived from 2009 to 2015. Queensland was a novelty for me because it was the first time I lived in a small town. Before moving there I’d always lived in big cities and the culture shock was significant. It’s situated on an estuary and is near a surf beach and in fact my unit up there was about 500m from the ocean.

It took me a while to get used to Maroochydore but I was living a regular life with a set of daily routines that would see me going to mum’s flat in the morning for breakfast, then again in the late afternoon so I could cook dinner for the two of us. So ‘Bondi’ has a twin significance for me in a way that now gives me cause to think about different parts of my life when I am exposed to it, as I am every time I go into the living room.

I am curious as to how my perception of the painting would change viewing it ‘in situ’ rather than in cyberspace. Perhaps the decorative quality would be more subdued and the impact heightened by a holistic view. Environment is such an important factor. For example I see it working well in a light and breezy window location, perhaps with greenery, if the new abode has such a spot...

Actually this was one of the works the stylists used in my apartment when the real estate agents were selling it for me. I had to sell the apartment in order to buy the house the collection of art is now kept inside.

The Pyrmont stylist chose for her hang blue-and-green works in my collection, and ‘Bondi’ was put right next to the front door, so that you’d see it as soon as you came inside from the lift lobby. I’ve put the work in the living room (see initial photo above) where it fills a wall with the accompaniment of smaller items adding texture and playing off its vibrancy. The strength of the colour scheme of ‘Bondi’ certainly makes it a striking piece and it’s the first thing you see when you enter the living room, which is dominated by a purple couch and pink curtains. I also have a lot of bookcases so a large and powerful painting will always work in my place.