Event: First Tuesday Book Club, ABC TV, 10:00 p.m.

The books featured:

The Shadow of the Wind, Carlos Ruiz Zafón (1st pub. 2001, trans. 2004)

Longitude: The True Story of a Lone Genius Who Solved the Greatest Scientific Problem of His Time, Dava Sobel (1995)

Originally, Helen Garner’s controversial non-fiction account

The First Stone was slated to be discussed, and Susan Wyndham tells us in

The Sydney Morning Herald’s weekend edition that the author of

Longitude, Dava Sobel, was originally to be on the show. “But Sobel had to drop out,” she writes, “and

The First Stone gave way to

Longitude …” because … well, it’s not clear from what she writes. However, according to Jennifer Byrne, the host of the show: “We will do

The First Stone later this year or next year.” We look forward to that.

Both Sobel’s book and Garner’s were published in 1995, which makes both books seem quite old: over ten years old, in fact.

Sobel is an American author who was born in the late forties: on 28 October 2005 she was 58 years old, according to

an interview she gave to Powells.com.

“Carlos Ruiz Zafón is a Spanish novelist. Born in Barcelona in 1964, he has lived in Los Angeles, United States, since 1994,” according to the Wikipedia.

Two of the panelists were the same

as last month: Jason Steger (

The Age’s books editor, who has just been at the Melbourne Book Festival: “It was a gruelling experience, but it was terrific,” he said) and Mirieke Hardy (“a screen writer and radio host and has carved out a degree of online notoriety as a blogger”).

But new to the panel this month were Pru Goward, federal Sex Discrimination Commissioner (“and also a journalist, a broadcaster, and author; maybe a future MP, and a very keen reader,” added host Jennifer Byrne. “Have you got a favourite?” “I‘ve got a favourite,” said Goward, “At the moment I think it‘s

The Reader by Bernard Schlink. I think it’s an amazingly pared-down book with a number of layers, complexities.”), and John Safran, a TV personality (“given your interest in religion, do you read a lot of religious books?” asked Byrne. “I do. My favourite religious book is

Satanic Verses by Salman Rushdie, which sounds like I’m trying to be a smart-arse … but it’s a fantastic book.” “Anything with Satan in it is cool. It has to be the biblical Satan, not some sort of lame-arsed, just some sort of, I don’t know, atheist Satan knocking some horns on. I don‘t like that.”).

Carlos Ruiz Zafón’s

The Shadow of the Wind was first up for treatment: “A huge international success when it was first published a few years back,” began Byrne. “Now [it is] re-released in this smaller format. The story, of course, is precisely the same.” After the initial visual blurb, the conversation (and argument) started.

“So, it’s a thriller, a coming-of-age story, a romance. A page-turner, basically, with a plot as fast and twisty as a fair-ground ride. Jason, would you buy a ticket on that ride?” “I certainly would, it’s a most wonderful book,” replied Steger. “You get yourself completely lost in it. It’s a great, big, baggy novel that takes you to Barcelona. It’s full of atmosphere, it’s full of extraordinary characters, and I think they’re all really well portrayed. It’s a wonderful read.” “What about you, Marieke? Did you like it, from the get-go?”

“No,” replied Hardy. “Not at all. It took me a while and it made me question myself as a reader a little bit. Because I was quite foldy-armed cynical about it. And it was interesting [that] he’s written young adult fiction before. And I felt the beginning for me was very flavoured with wide-eyed, young-adult fiction. But by the time I was into it I was completely gripped, also. I was just swept away.” “It worked for you?” asked Byrne. “Absolutely.”

“Pru?” “Oh, a great page-turner, and I love stories about the coming of age of young people, I loved that. And I was engrossed by him, the central character.” “Daniel,” prompted Byrne. “Yeah. And I thought it was very Spanish. It reminded me very much of Marquez’ writing, that same sort of weird, supernatural-meets-gothic-meets-home-down-coarseness. And I thought it was a great read.” “There you go,” piped up Byrne. “We all agree. Or do we?” turning to Safran.

“Usually, you hate a book by about page ten. I knew I hated it from page one. It’s like: is there any worse combination than dumb and pretentious? … The first page, it’s so obsequious and pandering to its audience. It’s: ‘little Daniel, and no-one understands him, but he’s lost in the world of books,’ and we can sit there and go ‘oh, that’s just like me, no-one understands me but I’m lost in the world of books.’ The only way this book could pander to its audience more was if page one was like: ‘I’ve always thought that forty-something women who sit around on chairs and talk about books are the most beautiful women in the world.’ That is the only way it could have sucked up more.”

“I was not with you to that degree,” responded Hardy. “… obviously you are quite snooty about it.” Hardy liked the Fermin character, she said that “that, to me, was where the book came alive”. “He’s a really well fleshed-out character, all his dialogue is just impeccable,” she added. “I think he’s really colourful without being corny."

“I think there are so many characters in there,” went on Steger. “Not even the large characters, but tiny characters, who are just captured really, really well. I mean, there’s a description early on where he talks about anarchists, and he characterises anarchists as people who ride bikes and wear darned socks. I just thought that was brilliant.” “That makes me an anarchist,” he drolled.

“He’s thought up new ways of being a bad writer,” countered Safran. Groans from the others. “I’ll tell you what I mean. The narrator is a grown-up, but he’s kind of describing what he experienced as a fourteen-year-old boy. So, in the narration there’s this ridiculous conflation of how a fourteen-year old would look at something, with how a grown-up would look at something. Like when he meets a woman, right? When you’re fourteen, a sixteen-year-old is like another generation. An eighteen-year-old is, like, two generations away. And anyone who’s twenty might as well be thirty or forty, right? We’re meant to believe that when he’s fourteen, he sees this twenty-year-old woman and: ‘she looked young for a twenty-year-old.’ Then he meets this other twenty-year-old woman, no, sorry twenty eight. He goes: ‘she was twenty eight but she looked like she had about ten more years on her.”

“I don’t agree with you about the writing,” said Seger. “Because I think some of the descriptions of the characters are absolutely brilliant. And he does those… in very fine brush strokes. Yeah, at times, he lays it on with a shovel, I think.”

“But I think, while it is a very baggy plot, and I love that, and I know you mean that positively…” said Byrne. “You can really get into it,” said Steger. “I think the descriptions of the characters are really sharp.” She quotes from the book.

Some of the discussion was lost in the give-and-take.

“Is the test of a great book: does it play on your mind afterward, and do you come back to it seeking to resolve things?” asked Goward, who had been silent for most of the previous discussion. “It doesn’t do that, there’s too much. You can’t go back to it.” “Thank you,” said Safran.

“The greatest character, in lots of ways, is Barcelona,” said Byrne. “Did it work for you?" she asked Goward. “Yes, I love the gothic and I love the Spanish, and I could just see it as a movie, I could smell it.”

“It does seem a little too much,” she summarised. “I could have done with an extra couple of hundred pages,” said Steger. “But I still think that the whole of the atmosphere, the story, the characters, I think they actually overcome any flaws…” “Do you think though it was more gothic than gothic?” asked Byrne. “It reminded me a little bit of, you know, the albino monk in

The Da Vinci Code. He was not only a giant and a monk, but he had thorns around his neck, and he was a killer…”

“I think the author was very pleased with himself,” said Safran. “So, in the middle of a chapter he’d drop some line where he’d go: ‘it was snowing, it was like God’s dandruff.’ And I’m kind of thinking: OK, passable, I’ll let that go, right? And then, he’s so pleased with himself he has to end the chapter with ‘and then I walked down the street under God’s dandruff’.”

“I couldn’t believe it was 512 pages. I went to my bookshelf and took out the New Testament. That’s 423 pages. This guy thinks he has more ideas than God.”

“I think, generally speaking we’re talking favourable except a very strong dispute from Mr Safran. And I just thought it was a little bit corny in places.” “I felt I had been wearing a dress or something after reading this. And then I had to go off and read Biggles or Boy’s Own Annual, to reclaim my masculinity.”

“Well the evidence is it’s sold over a million worldwide, and they couldn’t have all have been women,” said Byrne. “Nearly as popular as Friends,” countered Safran.

This discussion took just over 13 minutes to complete. Sigh. I’ll not reproduce the discussion over

Longitude, as it’s getting very late now and it’s high time for me to post!

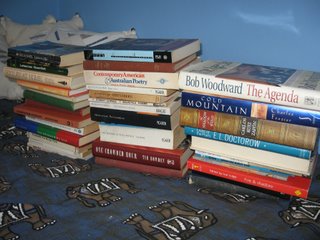

I arrived at the 2MBS FM book and record bazaar just after nine o'clock this morning. The trip to Gosford took about an hour and a half through the grey-green bush and pink-and-tan sandstone cuttings.

I arrived at the 2MBS FM book and record bazaar just after nine o'clock this morning. The trip to Gosford took about an hour and a half through the grey-green bush and pink-and-tan sandstone cuttings.